The unwinnable war over screenshots

Header image used with permission from K-putt.

All other images used with permission from Dead End Thrills.

///

This image has been causing trouble on the internet.

For once, the argument isn’t about the content in the videogame that is the subject of this image, or even about the game in the image at all. This debate is about the image itself. It’s over the value and worth of screenshots, and it has been raging in comment sections for the past few years.

Here’s an example of how it goes down:

Someone posts an article about screenshots, maybe using the term “art” or “artist” somewhere in there. Scroll down a bit, and it won’t take you long to see it.

“What a joke, anyone can take nice screenshots. How dare you call him an artist.”

Responses quickly pile up. “I suppose anyone can take great pictures with a camera too. Is photography somehow not an art?” “What a joke, anyone can put paint on a canvas. How dare you call him an artist.”

More posters come to the aid of the original criticism. Shots are fired back by defenders of the work in turn. A few posts later, and we’ve somehow got to “Please kill yourself. It will make the world a better place for us all (excluding you.)” (It’s worth noting that these are all direct quotes from actual commenters.)

People still want to fight about photography, art and the image.

This is not the only post I found in my research on this debate in which a commenter suggested that another commenter off themselves, all over a difference of opinion concerning screenshots. If you can find an article where the work of screenshotters, as some style themselves, has been posted, and it does not devolve into vicious name-calling, you’ve found a rare corner of this part of the net.

The classification of these images, whether or not they should be called art or are even valuable and worth seeing at all, sets people off in a big way.

Those who harbor a dislike of virtual photography, as it is sometimes called, have a problem with the medium that is simple to state: the subjects of virtual photographs were almost never designed by the photographer. The art is, they say, in the subject and not its image. It’s the game’s designers who have created all (or nearly all) of the value in the image, and for someone to post a screenshot and call it their own work is arrogant, at best. Others disagree, saying that composition, technical knowledge and heavy equipment are required to create these images.

Unsurprisingly, little is ever solved in these arguments. People just fight until they get fed up, bored, or both, and then they wander off to other corners of the net. But they leave behind documentation of something that is quite interesting: over 175 years after the commercial introduction of photography, people still want to fight about photography, art and the image.

///

2014 was a big year for the image. From a bombed TV show named Selfie, to questions over ownership and privacy and complicity with the release of stolen images of nude celebrities to a movie nearly sparking an international conflict—the power of images has had a massive impact in this bygone year, as well as in the years just preceding it.

One man in videogaming has, perhaps, seen the power of imagery affect his life over these last few years more than any other. His name is Duncan Harris, though most will know him better as Dead End Thrills, and he is a creator of screenshots. The sense of compositional assuredness in his work, in fact has made him a sort of vanguard of the form. The assumption is that Duncan Harris and others believe that they create art, and this position is attacked and defended in the comments without hesitation.

However, when asked if it was important to him to be called an artist, Duncan responded by saying simply, “No,” adding, with tongue in cheek, “It tends to appear on my paycheques, though, so I guess it’s important to whichever accounts department has to fill the payroll forms in.”

In fact, as opposed to the image of a self-promoting artist that both sides of the debate seem to want to give him, Duncan prefers to stay out of the limelight, saying, “I try to stay invisible on the site as much as possible. […] A lot of people don’t really know or care who takes the shots, and that’s fine, it means they’re focused on the games.”

These issues of the authenticity of an image are not new.

Duncan says that the reactions from game creators to his images have been, “Always positive. It’s free publicity, so why would it be anything else?” That Duncan frequently gets access to special builds for games and works with developers back this up further.

///

What is perhaps most interesting about the debates surrounding the work of Duncan Harris and his contemporaries—people who go by names such as K-putt and PixieGirl4—is something few involved with these debates are saying:

These issues of the authenticity of an image, of ownership and skill, of what is and is not art, are not new. ?

In fact, these very same subjects have been the centrifuge of debates that have been raging for over a century within the larger fields of photography and art itself. They’ve simply been transferred to a new medium, and a new field of conflict.

One could point, for precedent, the outrage surrounding Marcel Duchamp’s “readymade” sculptures, which were created with everyday objects and then declared to be art, or at Yves Klein’s paintings that can be interpreted as intended to give him ownership of a certain hue of blue (which he deemed International Klein Blue). Warhol’s silk-screens, and subsequent legal trouble with the photographers whose work he turned into said screens, are perhaps the most popular example of this argument at play. Photography is no different. I once had a History of Photography professor explain that initially many in the public feared being photographed when the Daguerreotype process was brought to the masses, as the ability for another to own one’s likeness in such an authentic representation unsettled people. It wasn’t until celebrity photos began being disseminated en masse that the public took up the practice of sitting for portraits.

It is, however, where the two fields of art and photography meet in creator Sherrie Levine that I think it can be seen most clearly that this debate is neither new, nor is it something we’re likely to solve in internet comments sections.

Levine is a creator who takes the creations of others and duplicates them, often exactly. Her most famous work was a series of photographs that she displayed at New York City’s Metro Pictures Gallery in 1981, which were actually photos she had taken of photographs by another photographer, Walker Evans, that were exact duplications. No retouching was done, no manipulation. The Evans images were already very famous, and Levine made no attempt to hide her appropriation, calling her series of images After Walker Evans.

Levine’s work actively courted, and continues to court, the very debates that we see cropping up around Duncan Harris today, and she did not even attempt to put anything of herself into her images, unlike Harris and his contemporaries do. The debate itself, the questioning of authenticity and ownership and value of an image, the controversy surrounding photographic appropriation, is Levine’s art.

Right now, internet commenters are asking Sherrie Levine’s questions—they’re asking the questions people have always asked about images, and they’re finding, as people always have, that there is not a consensus to be found in answering them.

///

“So who’s the artist?”

The debate over these questions will only get stronger and more complex in the coming years.

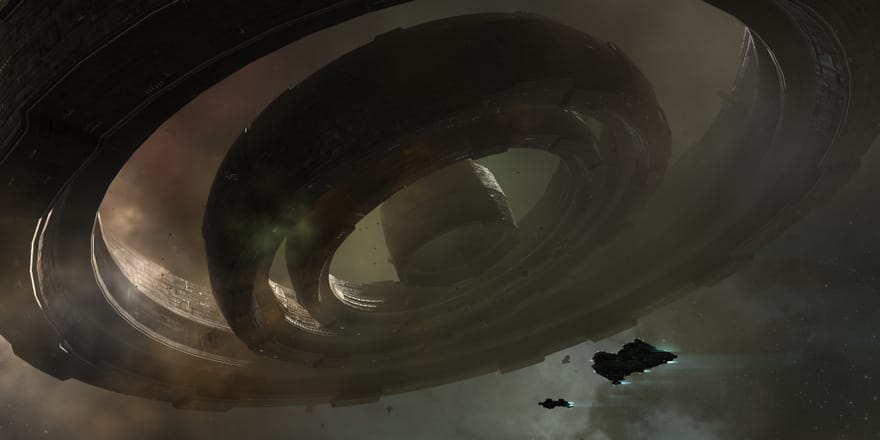

Duncan Harris showed me one image with the disclaimer, “If you want to really muddle your findings about screenshots being art,” and proceeded to show me something that was not a proper screenshot at all. Instead, what he showed me, and which we unfortunately do not have permission to share here, was an unofficial “rare example of screenshots being built from scratch using a game’s assets and engine in an editor environment,” which Duncan took of an EVE Online ship for an art book developer CCP was putting together. Says Duncan, “They’re not quite screenshots because those scenes don’t happen in EVE Online, but they use CCP’s assets and tech.”

“So who’s the artist?”

Duncan told me this is a “pretty extreme example of ‘screenshotting’,” and added that it “probably isn’t screenshotting at all” and is instead “borderline CG art,” but the example makes something clear here: this debate will become more confusing before it clears up.

And this is far from the only way the future will do that muddling. One artist pair, Eva and Franco Mattes, recently created a piece which consisted of screenshots of videogames they had created themselves, and then presented the images as art. In Minecraft and Second Life, it’s hard to say that the developer of the game created the buildings that are often screenshotted, and they may even have been created by the screenshotters themselves. Moore’s law of consistently advancing technology tells us that, at some point, someone will create a perfect recreation of an SLR camera in a highly detailed, near perfect virtual world, and someone using virtual reality equipment will take an image with that. At that point, even using the term screenshot seems archaic and inaccurate. But in reality, it’s not much different from what Duncan Harris does; it’s just better tech.