This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

Mental illness is a complex, nuanced subject that many forms of entertainment have tried to faithfully portray. Movies such as Silver Linings Playbook and TV series like Showtimes’ Homeland have succeeded to varying degrees, but many attempts fall into clichés that perpetuate misinformation. Despite some mishaps like Eternal Darkness: Sanity’s Requiem, where those who suffer from mental illness are seen as defective, video games are a powerful vehicle for exploring this topic in new and enlightening ways.

“The challenge games face in regard to the mental health discussion is how to bring these issues to light without falling into the common traps,” Patrick Lindsey wrote in a 2014 opinion piece for Polygon, noting that horror games tend to be the guiltiest of misrepresentation. “Mental illness is horrifying for those who suffer, and it can drastically affect one’s perception of the world, but to focus solely on the spooky and the irrational is to only tell half the story.”

Because players adopt the perspective of the game’s characters, they experience the symptoms and thinking patterns of different mental illnesses firsthand. This gameplay method could help increase understanding and empathy when done well. “Videogames in particular have the uniquely awesome power to virtually place you directly in the shoes of another person, creating incredible opportunities to educate, raise awareness and build empathy around topics like various psychiatric conditions,” said Erin Reynolds, creative director for the horror adventure game Nevermind.

Researchers have found promising leads when using videogames to treat individuals suffering from illnesses like PTSD. Through a method called “exposure therapy,” virtual reality games help patients with anxiety and phobias address their symptoms in safe, controlled virtual environments. By understanding the link between videogames and mental illness, experts can help patients develop coping mechanisms.

Games like Nevermind take a different, yet equally ambitious approach to addressing mental health issues. It uses optional biofeedback technology to help players manage their fear and anxiety response to the scary scenarios in the game.“From the very beginning of Nevermind’s conceptual development, I knew I wanted to work within the horror genre, not only because it would allow for an aesthetic I’m personally drawn toward, but also because of the capabilities horror games have to evoke a physiological reaction and leave a lasting impression on the player,” said Reynolds.

How horror manifests itself in Nevermind is important. While many games still fall prey to perpetuating stigma and misrepresentation, horror games like Evil Within in particular continue to use mental illness as set dressing, vilifying the people suffering from it. Instead of jump scares, however, Nevermind uses “twisted, surreal and oftentimes disturbing settings, sounds and imagery.” The player’s imagination is ultimately more dangerous than the game world itself.

The player’s imagination is ultimately more dangerous than the game world itself.

Reynolds said this is similar to how things often play out in real life. “I’ve found that the things we fear or worry about—be them an upcoming due date, speaking in front of a large group, taking a test, etc.—rarely are actually directly harmful to us,” she said. “Rather, it’s the unaddressed feelings of stress and anxiety that we experience leading up to that event that drain our energy and serve to harm us more than anything else.”

Nevermind wants to teach people how to face their fears head-on, tackling them and gaining the confidence to handle fear and anxiety both in the game and in real life. In doing so, it not only helps people who may be suffering from mental illness, but also begins to chip away at the unfortunate stigma attached to it.

“The more we accurately represent the complexities and ubiquity of all types of psychological distress, the less ‘unknown,’ and thus the less ‘scary,’ it will be,” Reynolds explained. “People might be able to see that an illness doesn’t define them; rather, it is just one aspect of life that the individual has an ongoing struggle with.”

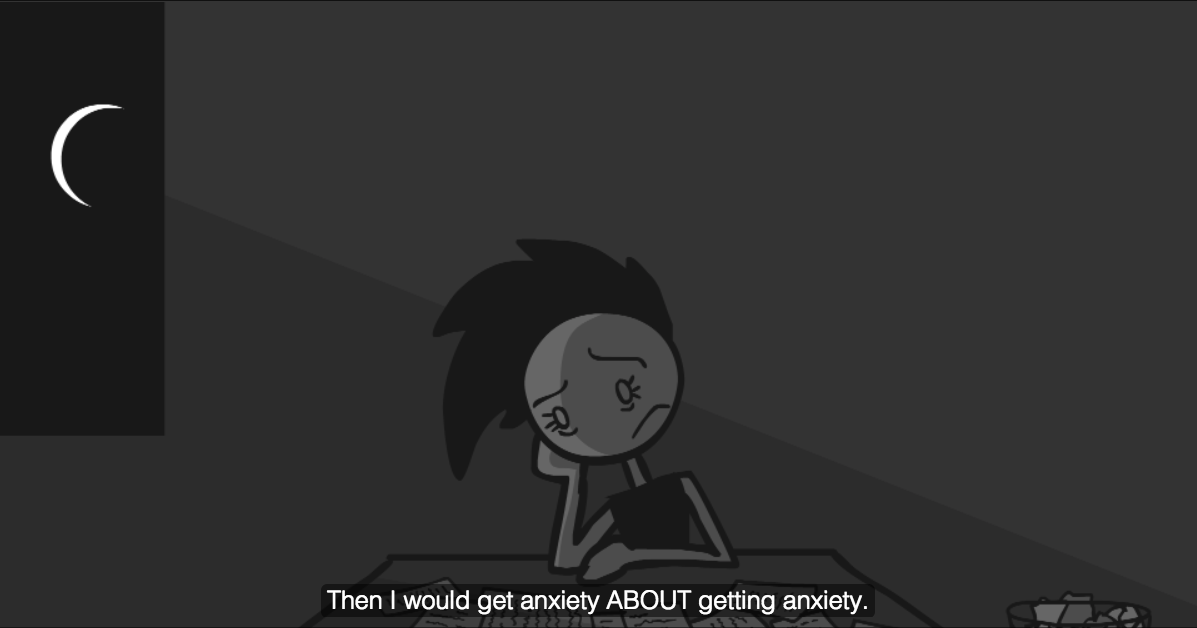

Although creating games that improve empathy and reduce stigma may be a great start, the question of how to treat mental illness remains. Here, too, videogames might have an answer, according to Nicky Case, who creates everything from augmented and virtual reality experiences to games. Case has explored the topic through what he calls “interactive explanations.” Designed in a manner similar to a brief animated short, these exploration narratives provide powerful visual cues and viewer feedback to help illustrate how different complex societal or psychological systems work.

His latest interactive explanation is Neurotic Neurons, a quick primer on the way our brains learn and can be re-trained through treatments like exposure therapy. Demonstrating how neurons create and destroy thoughts, Case makes conquering his lifelong anxiety not only feel possible but actionable. “While doing research for it, there was something stressful looming over me, and I wanted to avoid it,” he said of his own struggles while making Neurotic Neurons.

“Just in time, I stumbled across exposure therapy and learned that while avoidance may feel relieving in the short term, in the long term it just prolongs the anxiety. That really helped me.” Case’s theory is that he can help people understand how to change the way they think through safe exposure to phobias and stressors. This works beyond anxiety and mental illness issues, too, as he’s contemplated using the same method to help people learn empathy toward other cultures and identities.

Neurotic Neurons provides a powerful explanation: Our brains are malleable forms that can, over time, be re-wired with healthier, safer thoughts. “It can be worked through,” he said. “It’s hard, but it can be worked through.”