V R 2 asks how much faith you’re willing to put in game makers

The town of Marfa is a repository of modern art and little else in the middle of the Texan high desert. “Whether you aim to remember history or forget it,” reads the first line of the welcome message on its website, a blockish, primitive piece of Internet. That is not the most promising of taglines, but the widget to the right of that text nevertheless advertises a stocked cultural calendar. And why shouldn’t it? Since the late 1970s, Marfa has been home to a series of installations that achieve their potency by appearing on the edge of the world.

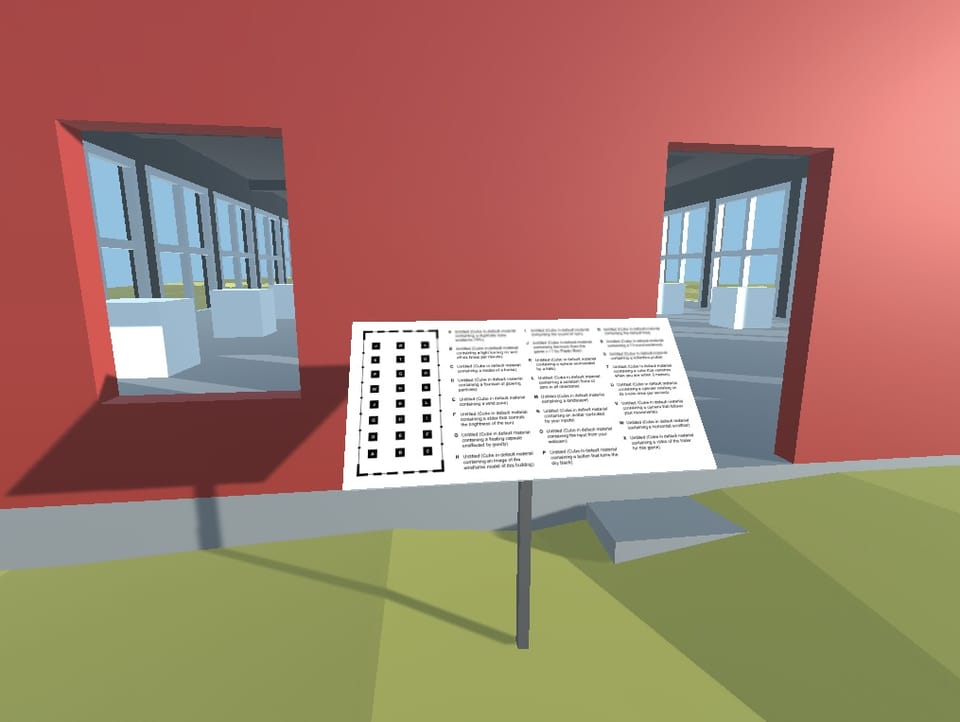

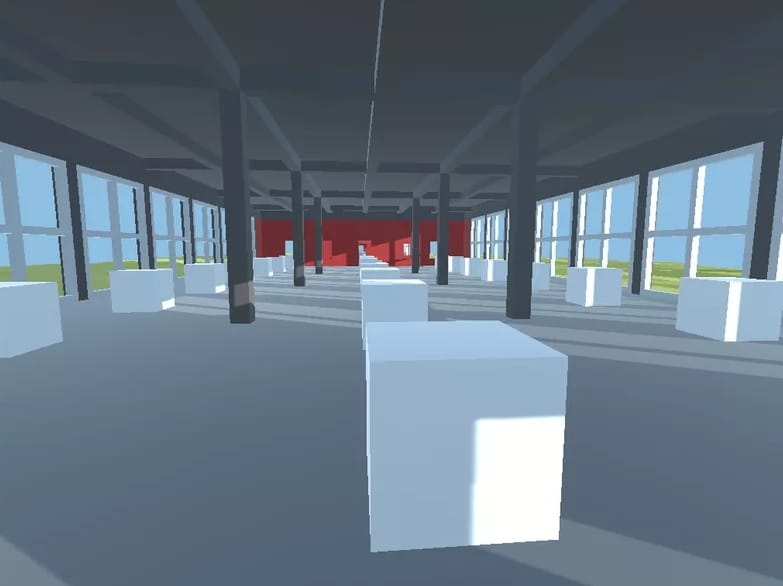

Among the earliest of those installations is Donald Judd’s “100 untitled works in mill aluminum,” which serves as the inspiration for Pippin Barr’s latest game, V R 2. Everything here does what the label says: V R 2 is the sequel to V R 1, and Judd’s installation is indeed a series of 100 aluminum cubes. The cubes are arranged in neat rows in two gun sheds, which Barr has recreated in low-poly form. The main difference is that Barr’s installation has 48 cubes to Judd’s 100, but you’re unlikely to miss the remaining cubes.

The trick to Judd’s installation is that each cube, while identical on the outside, contains something different on its interior. You can’t see it, but each of these cubes is different. Or at least that’s the theory. You can’t really prove or disprove it. But the boxes are all different and thus theoretically interesting. V R 2 also promises that its boxes are all different; there are placards in front of each barn explaining what is in each box.

a provocation about the player’s trust in game creators

In the grand tradition of Pippin Barr works, V R 2 is interesting in that it might also happen to be a game. If you believe that there are different things in the boxes—or anything at all—then it is a mystery game, albeit one that cannot provide any answer. If, on the other hand, you have less faith in Barr, V R 2 is simply a walk through two sheds with some cubes on the floor. The latter isn’t exactly an intriguing game, but it’s also basically the same experience. V R 2, in other words, is perhaps a provocation about the player’s trust in game creators. In any game, you put yourself at the developer’s mercy, and that transaction involves a certain amount of trust, but here that transaction is the entirety of the game.

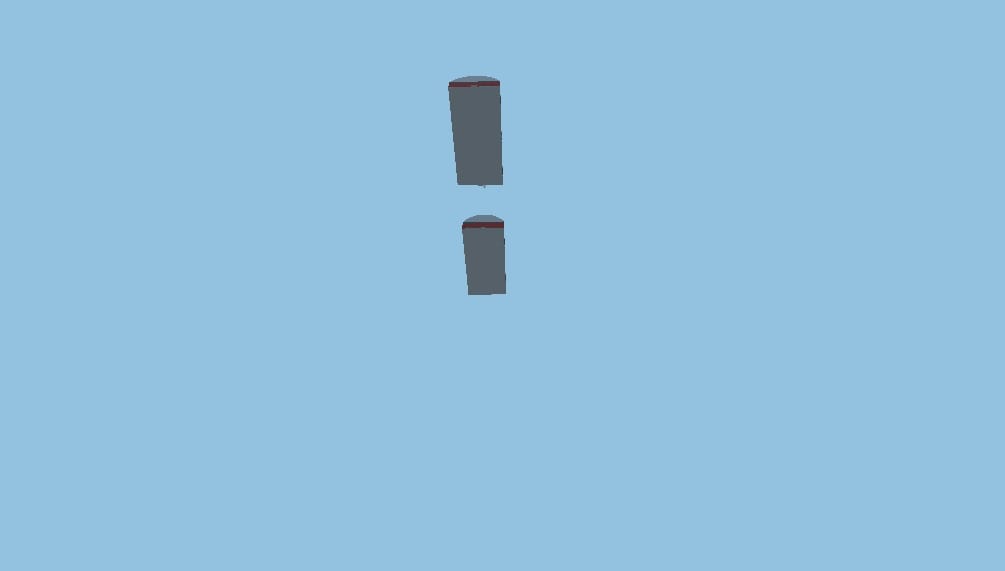

The intrigue of V R 2, however, only lasts for so long, which is why I decided to do the one thing you cannot literally do in Marfa, Texas: I walked off the end of the earth. V R 2’s polygonal groundplane extends beyond the sheds, but not so far that you cannot reach it when you’re done staring at the blocks. That little stroll gives you enough time to consider how much you trust Pippin Barr. It allows you to stretch the experience of V R 2, because walking through a shed doesn’t always do the trick. So I stepped off the end of the world and fell, and fell some more. There is little more to be seen from underneath the sheds; the barns have floors that prevent you from seeing through their cubes. Maybe there’s something in them. Maybe there isn’t. I don’t know; I’m still falling.

You can download v r 2 on Pippin Barr’s website, or play it in your browser here.