The rise of VHS horror games

The introduction of VHS cassettes in the 1970s was a revolution in bringing horror closer to people. Two decades before, television became the primary medium for affecting public opinion, trumping newspapers and radio. This bore a generation eager to sit around a humming electronic box in their living rooms, allowing all kinds of foreign images to infiltrate their homes. But these broadcasts were typically newsreels and government-approved screenings—images under state control. VHS put more power to the viewer, who could decide what to watch and when, just by inserting a box-shaped pack of plastic into a tape player and letting its innards uncoil.

It wasn’t long until VHS led to new scares. These weren’t confined to the grody, bootleg horror titles that ambitious, sick-minded amateurs distributed in hopes of getting a name for themselves. It included urban legends of serial killers and haunted tapes. The term “snuff film” came about in the ’70s after the Manson family were reported to have recorded their murders on camera. The idea spread and inevitably got tangled up with VHS as it grew more popular—rumors were that any innocent-looking tape could house footage of an actual, brutal murder; you wouldn’t know until it was too late.

a motif for death through technology

Beyond that, VHS tapes were known for their degradation, as is the case with any analog media. You played a tape too much and it would begin to decay. The images would be interrupted with static grain and piercing scanlines that clambered all over the screen as if a creature teasing its prey. The affect of this, to most people, is annoying: your favorite film is ruined, and so you’d have to buy another copy of it. But for some it changed the nature of the images to something else. The distorted images became a motif for death through technology—the visible signs of data rot. The nightmares and ghost stories came soon after.

Since the heyday of VHS, it has become a reference point in horror due to its associations. VHS glitches and tapes of real murders are plots in many horror fictions of the ’90s and new millennium. And it hasn’t slowed down, either. Within the past couple of weeks we’ve had the new Resident Evil VII demo making use of found footage to build up its scares and a trailer for the reboot of The Ring, which, if you didn’t know, involves a spirit that kills anyone who watches a certain videotape.

But that’s not all. VHS horror seems to be a rising trend in videogames especially. It came about in some bigger horror games of the aughts but, in the past couple years, has began to sprout its ugly flower (of flesh and blood) in the realm of independent games. Below, we’ve outlined the most significant titles in this emerging sub-genre, including the earlier examples that started it off and the more recent ones keeping it going. Between them is a combination of grindhouse aesthetics, actual tape horrors, and scares found inside recorded footage.

Silent Hill 2

The internet doesn’t need another impassioned love letter to Silent Hill 2 (2001), so let’s be as brief as possible. A VHS tape—a snuff film, actually—features at the heart of the game’s Freudian nightmare. The entire thing leads to that tape, peeling back layers of repression and psychosis until the truth is revealed in tracking lines and white noise.

After the physical grind of playing Silent Hill 2, with its combative controls, alienating obtuse dialogue, and endless staircases, you may wonder what it can reveal to top the shit it’s already piled on you. Don’t worry. It’ll deliver.

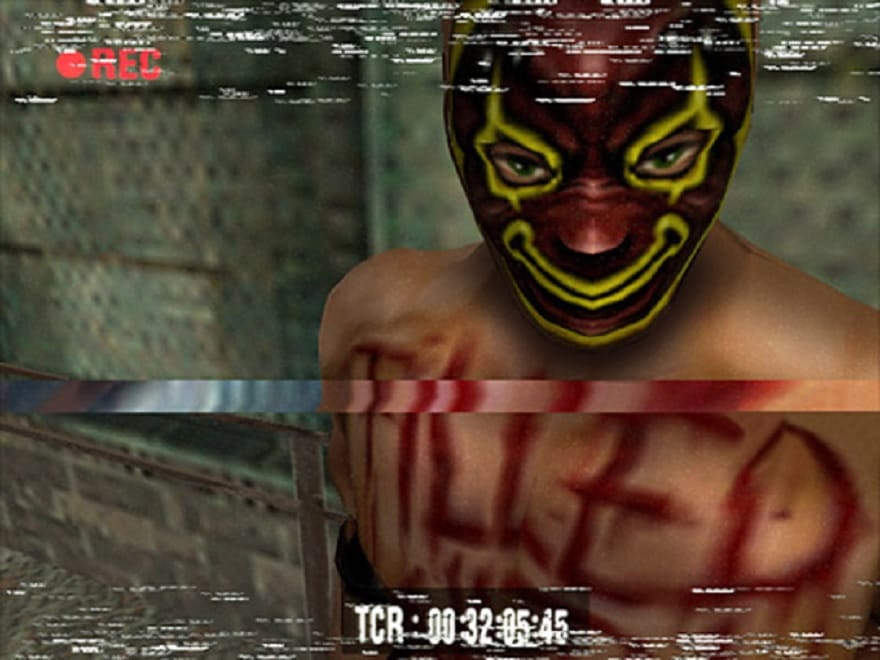

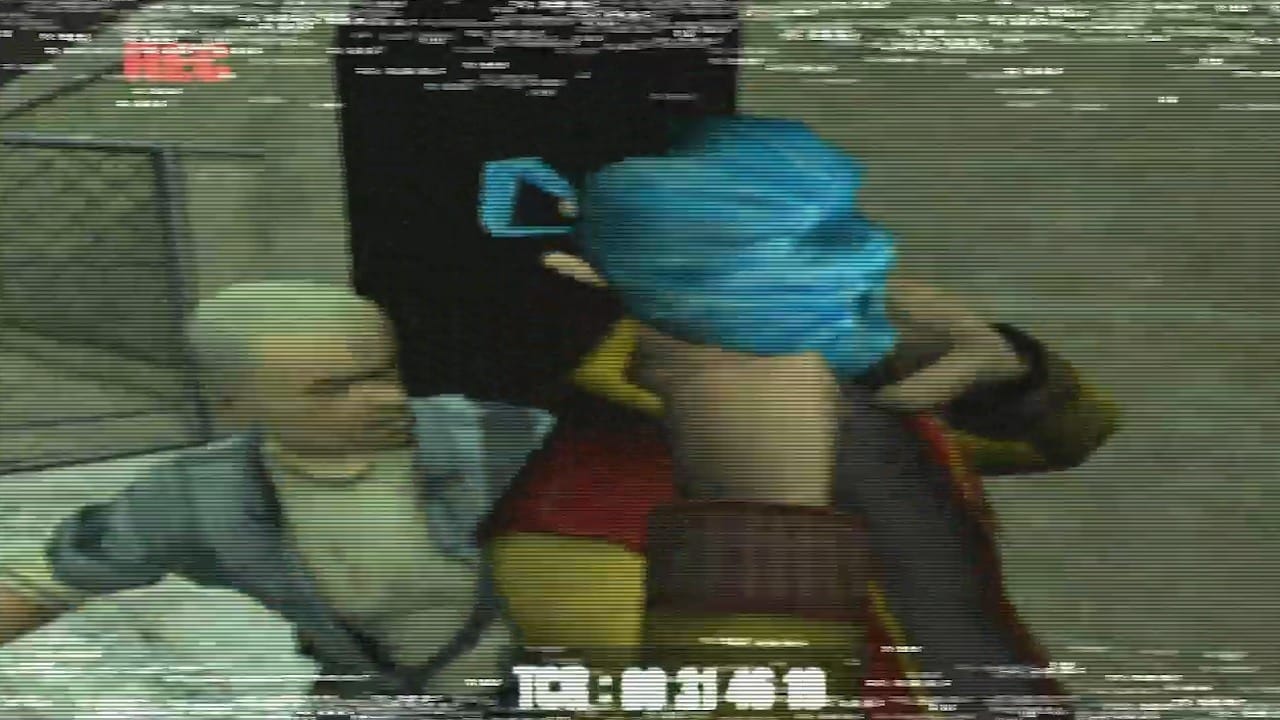

Manhunt (purchase)

The kind of experiment Rockstar doesn’t bother with anymore, Manhunt (2003) was a loving homage to grindhouse and found footage horror; a sort of mashup of August Underground (2001) and The Running Man (1987). Playing it now, it seems juvenile and clunky; but on release it caught a whole boatload of that sweet, sweet public outcry, as if the sight of one polygonal convict shoving a broken bottle into another polygonal man’s throat, blood gushing out in great MS Paint gouts, could singlehandedly undermine society as we know it.

The game was clever to couch its violence in crackling, snowy surveillance footage, letting the player enact po-faced executions for the pleasure of The Director; and of course, their own sadistic impulses, thank you very much. It’s Funny Games (1997) without the didactic finger-pointing; it’s Hotline Miami (2012) without the style. It’s frankly not much fun, and that counts as some sort of coup. How many games have the balls to strip murder down to its pathetic, depraved bones?

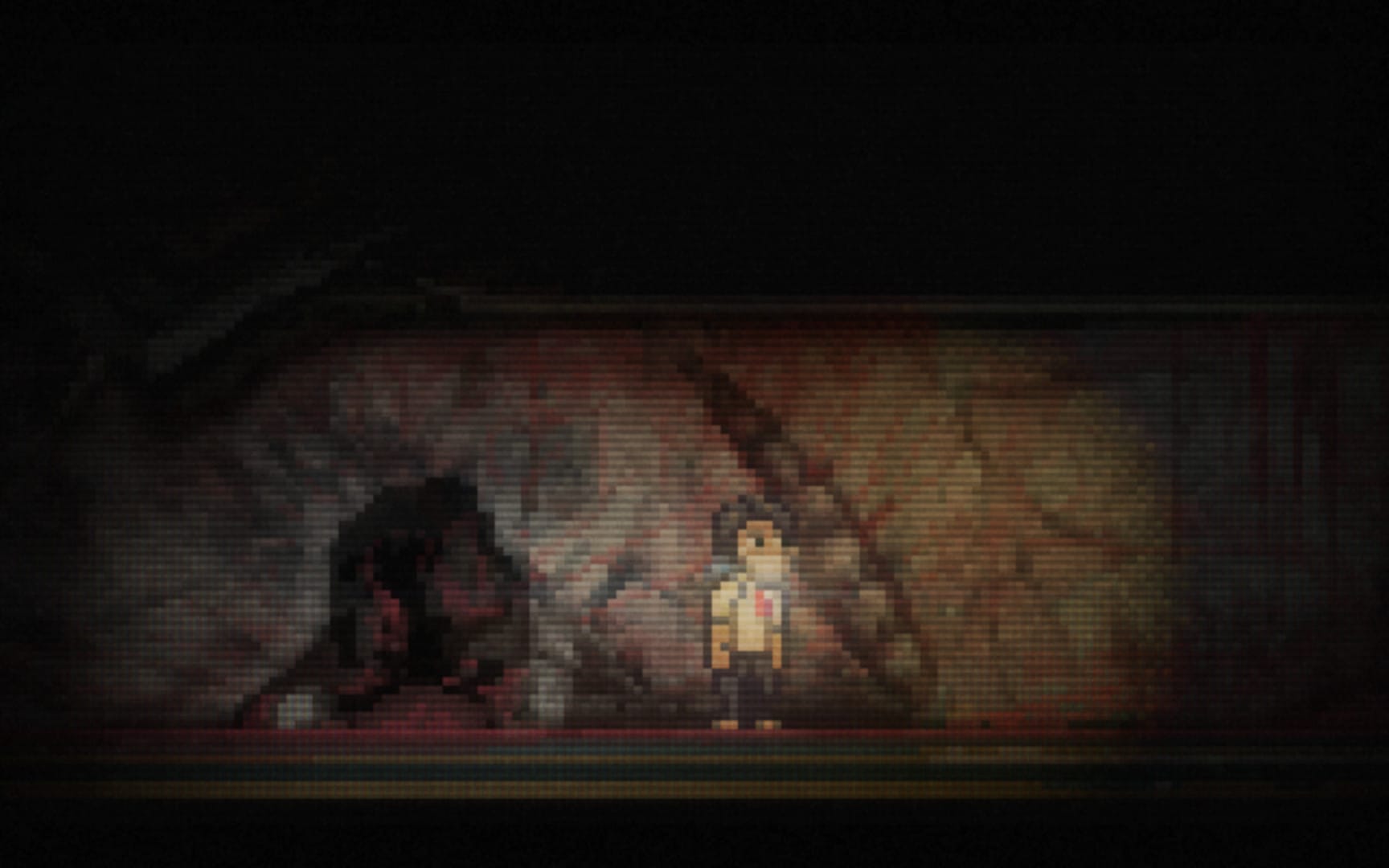

Lone Survivor (purchase)

One of the hundred thousand videogames that would love to be compared to David Lynch and Silent Hill; one of the handful that earns it. Designed (and scored) by Jasper Byrne—who notably cut his teeth on a lo-fi demake of Silent Hill 2—Lone Survivor (2012) is a resolutely grimy horror game. It doesn’t feature actual VHS tapes; instead its grainy visuals evoke the degraded wrongness you might find on an unmarked cassette in an abandoned, smoke-yellowed apartment complex.

A man with a box on his head; a theater lined in rich blue curtains; copious pills; strange dreams; a disturbing party. Lone Survivor is filled with surreal curlicues that adorn its unreliable, hazy narrative, piling atop one another—but are they distractions? Clues? You’ll get answers, eventually, but you may not like them.

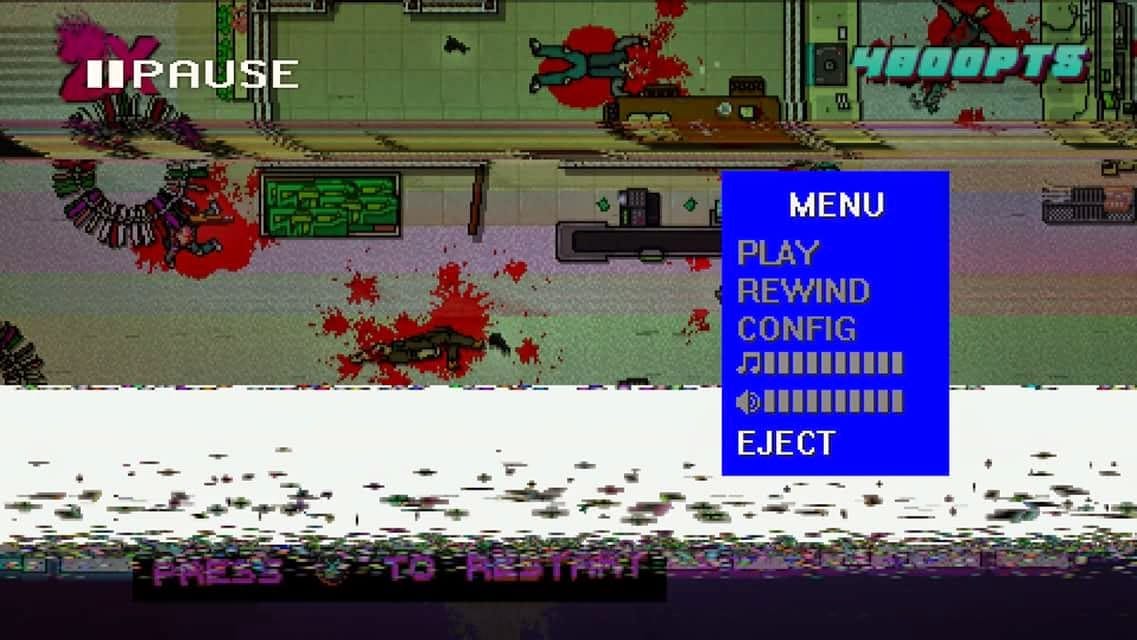

Hotline Miami (purchase)

Hotline Miami is desperate to feel dangerous. It may place you way above the action with its top-down view, but that’s only so you can better see the spread of bodies and blood once you’ve bludgeoned your way through the living. Everything is right up in your face—teeth bared—despite the lack of proximity.

But to achieve this effect the game’s creators had to find a way to make the pixel-art murder feel genuinely nasty. The tool they sliced it with? Grindhouse. Hotline Miami embraces its lo-fi aesthetic by borrowing a trick from Manhunt and framing its gory setpieces as a lone killer coaxed to decimate seedy street gangs. While the first game doesn’t go quite so far as having each massacre filmed on CCTV (as with Manhunt), the second one, Wrong Number (2015), recounts the events of the first as a slasher film in which you’re the star. And if that wasn’t enough, when you pause the game the menu is stylized as if a VHS tape, complete with static grain.

Five Nights At Freddy’s (purchase)

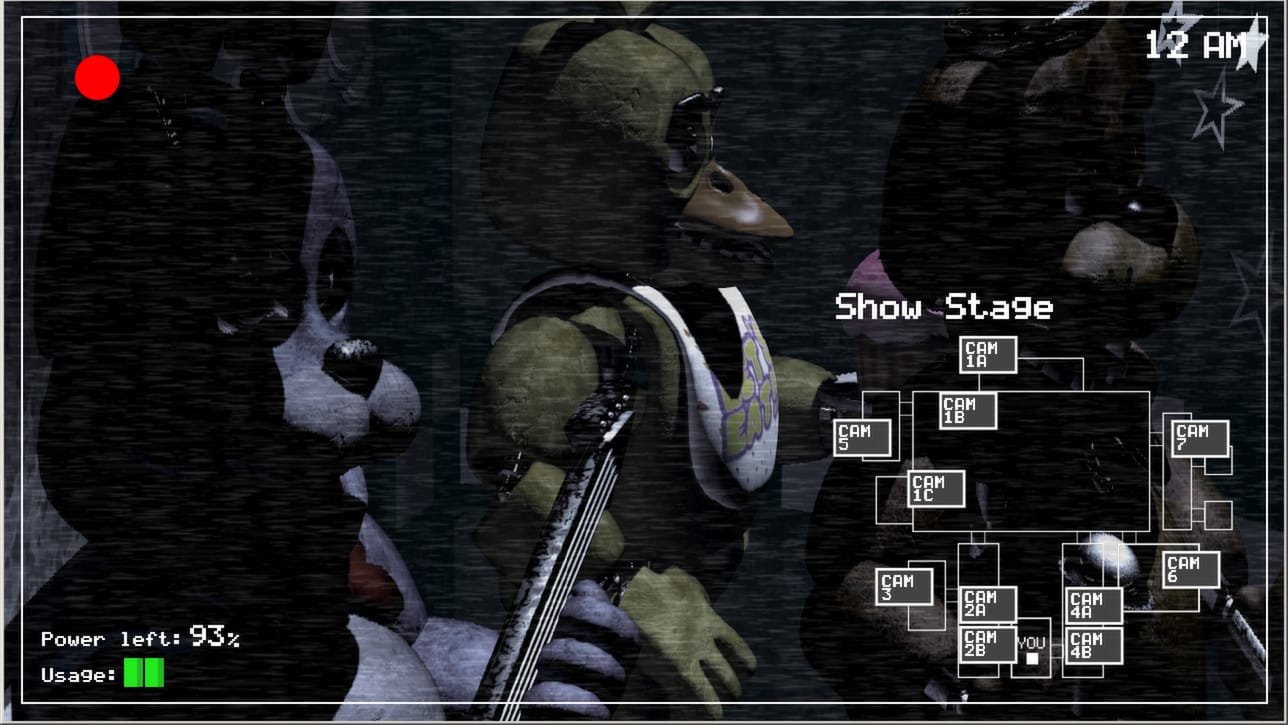

Before Five Nights at Freddy’s became the unexpected, viral, hurled-on-stage success (and major peeve for some) that it is now, it was a simple horror game with a neat idea. That idea is grounded in the game’s use of CCTV to unnerve you and, eventually, catch you off guard. You’re a security guard who must sit in an office, at night, and flick through the various video feeds that give you limited perspective of the pizza restaurant around you. It should be boring as heck. But, soon, you notice that the animatronic animals start to move around.

They’re creepy enough as is, but once you realize they’re alive and stalking you, they mount up to the level of terrifying. What doesn’t help is that your view is hindered slightly by low lighting and the static feed of the cameras. That degraded VHS aesthetic gives enough uncertainty to make you double take at times: did I just see a large duck peeking around that dark corner? No, surely not. Better check. Moments later you’re dead and you barely saw it coming.

Outlast (purchase)

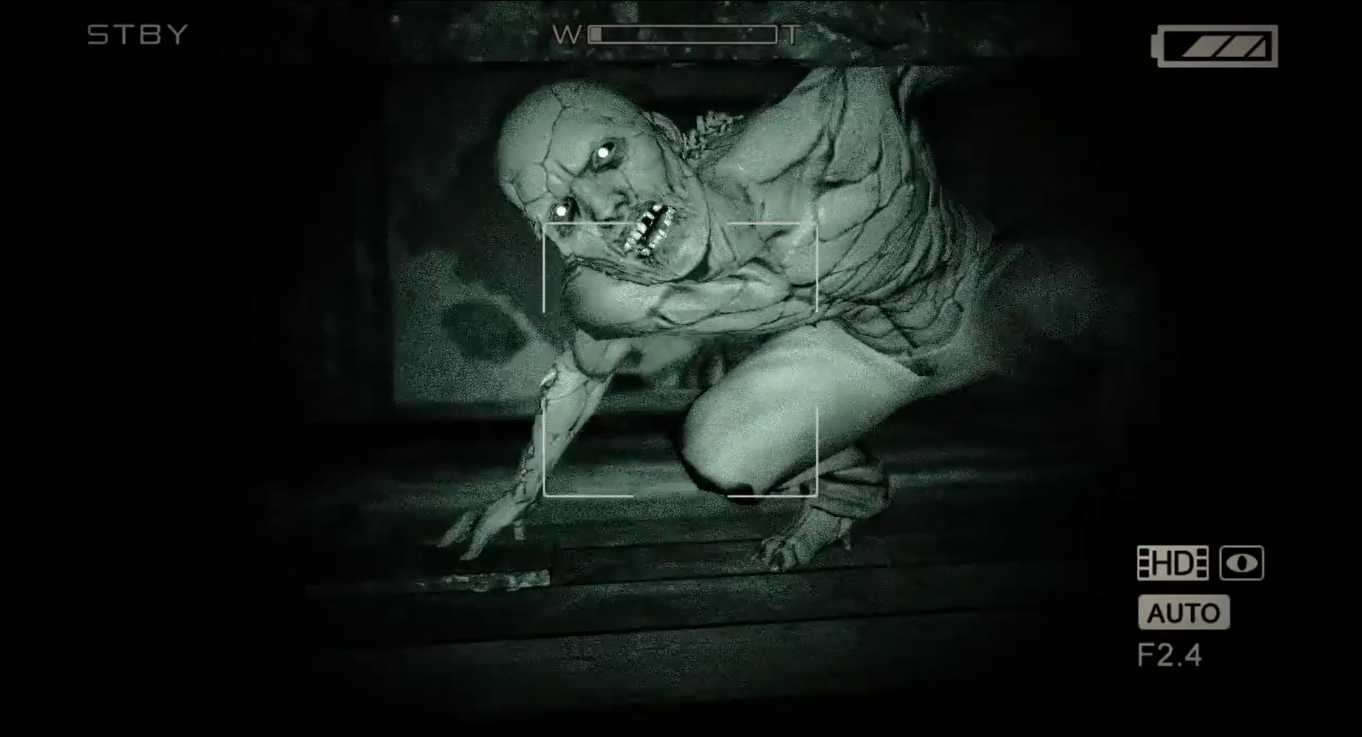

Ugh. It’s been two years since Outlast (2014) came out and the spasms it embeds in the nervous system still haven’t gone away. Part of the reason why is due to how it makes use of the camera. You’re a journalist who sneaks into an asylum where the patients are running wild and getting their vengeance on whoever messed them up. Questionable horror tropes aside, this journalist carries a camera with him (to, you know, journalize), which is often your only way to see in the dark due to its night-vision mode. Problem is that the camera absolutely devours batteries. That thing is hungry. And so if you want the safety of being able to see in the dark at all you’ll need to hustle every corner of that depraved place to find batteries to replace the fresh ones you put in there only 10 minutes ago.

Not only that, but having to view a large part of the game through a camera means Outlast resembles found footage films such as The Blair Witch Project (1999) and Quarantine (2008). That association is immediately unnerving as you get the sense that you’re the one creating the footage that someone will later find, once you’re dead. You imagine them, as you play, watching back your final moments, terrified of their own fate as they watch yours play out. The viewfinder of the camera you peer through also emphasizes how limited the first-person perspective is and how vulnerable you are in every given situation. Not that you need a reminder.

Sylvio (purchase)

Sylvio is basically ASMR horror, never rising above a whisper. You play as ghosthunter Juliette Waters, whose soft voice is a salve amid creepy seances, inexorable black orbs, and massive phantasmal shades. The texture of the game is defiantly analog; it crackles and fizzes and distorts with the reality-bending intrusion of the uncanny.

Playing Waters forces you to look, to investigate. Even if you get freaked out, she’s there to do a job. Scrubbing through the reel-to-reel she lugs around to record the voices of the dead, she automatically writes down what they say. You can only observe from behind a curtain of static and haze, at arm’s length from a professional doing her work.

Dead End Road (purchase)

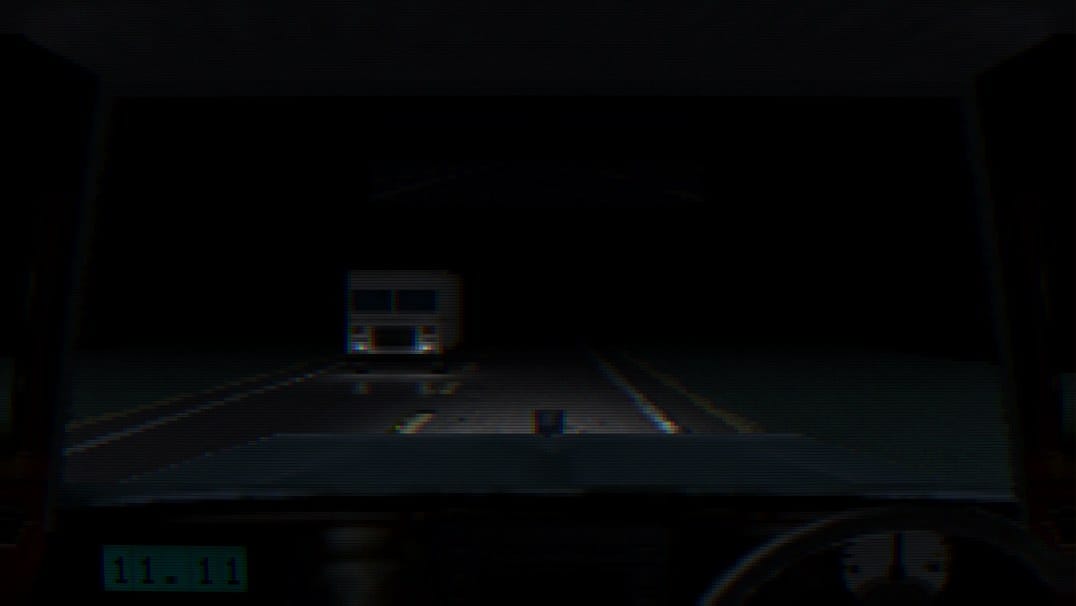

Y’know the credit sequence in David Lynch’s Lost Highway (1997)? The camera hurtles forward into the void, drunkenly capturing the play of headlines over the pavement, lane markers going rat-a-tat-tat right at you. Dead End Road is a game full of that. You drive all over a small town in an effort to rid yourself of a witch’s curse. Your car putters through heavy night, headlights struggling to cut the gloom. It’s never clear which lane the next car will come flying down.

It’s stressful! The lo-fi aesthetic adds a layer of claustrophobia: leaves and rain cutting across your view as the road twists queasily, the hard impenetrable dark always looming a few yards away. Smeary stretched textures, abrupt hallucinations, fake bluescreen errors, and the insistent waver of VHS tape combine to turn a series of, essentially, errands into something hypnotic and eerie.

Power Drill Massacre (download)

Power Drill Massacre is straight up not fucking around. That’s in terms of both its fuck-off-no horror and its callback to VHS slashers. You know how, in slashers, you moan at the actors on screen “oh, don’t go in there” or “of course she fell over right then”? Well, you are one of the actors this time around. You’re a teen lost in the woods who decides to find refuge inside an abandoned mansion. That would be a fine idea except a maniac with a drill cruises around there in bloodied overalls. Of course.

Sex is all about the climax. So, too, is horror. Theorists have written in the past of how these two opposite acts are connected in this way. It explains a lot of horror films and their many sex scenes. But the point here is that Power Drill Massacre lives for its climax. It comes so sudden that you’ll scream. A Michael Myers-looking dude comes out of nowhere and you’re dead. That’s the good ending, really. As if he chases you it can be much worse. Hurtling around corners not knowing whether he’s still behind you or if he has diverted to some other path in this hellish labyrinth in order to cut you off. You cannot endure that kind of tension for very long.

Anatomy (purchase)

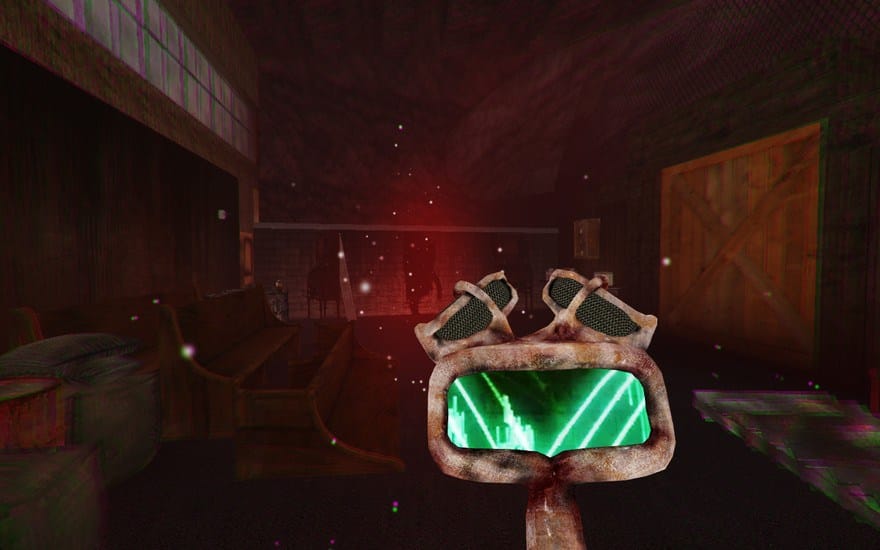

If there was any one title on this list that epitomized the VHS horror sub-genre then Anatomy is it. Perhaps the strongest horror game from Kitty Horrorshow yet, it has you creeping around a darkened house, collecting tapes, and then playing them back to hear an eerie tale. The first playthrough isn’t all that bad. It’ll be slow going as you creep around, dreading just about everything, but you’ll get through it. The hard part is going back.

And you will want to go back in, as Anatomy actually requires four playthroughs to experience everything. This structure is meant to mimic the act of playing a tape over and over, the visible static bands that hang over the screen worsening each time, the tape steadily chewed by the machine. All of those visual effects happen in Anatomy. But more than that changes too. Though, to say exactly what happens would be to undermine the whole point of the game. Give it a go and fear every minute you’re inside. You should. That’s how it’s meant to be.