Vib-Ribbon is a love letter to obsolete technology

Everyone remembers Vib-Ribbon. Everyone has forgotten Vib-Ribbon.

Has it been 3 weeks already? The cult favorite, MoMA-acquired, rabbit obstacle course music game from the turn of the millennium, Vib-Ribbon, finally saw official North American release for the first time ever on October 7, 2014 for Playstation 3 (PS3) and Vita. Vib-Ribbon, along with contemporaries like PaRappa the Rapper, is a progenitor of the music game as we recognize it today. The game presents players with timed button prompts that match beats and tempos of overlaid music tracks. Vib-Ribbon’s gimmick was that you could swap out the original Playstation game disc with your own music CDs and the game would generate playable levels out of any song you choose. However, it’s Vib-Ribbon’s inextricable relationship with physical, now-outdated media that makes its reissue somewhat strained.

Less of a reissue and more of a very belated publication.

Up until this year, Vib-Ribbon had only been sold in Japanese and European territories, but now is available as a downloadable “PSone Classics” game in the US and Canada, in addition to the prior regions. PSone Classics are pretty much exact copies of the original releases, and have not been updated to include widescreen formatting, meta-game Trophies, online leaderboards, or any modern console game amenities of the sort. So, Vib-Ribbon in the US is the 2000 European version of the game as-is, which actually makes it less of a reissue and more of a very belated publication.

At least for the PS3 version of the game, Sony was able to adapt and implement Vib-Ribbon’s signature CD swapping technology. This is where Vib-Ribbon retains what feels like old-school wonderment. There’s nothing quite like rooting through pages of CD sleeves, trying to pick out albums that you want to listen to that also might make for interesting levels. You feed the discs to the game console and eagerly wait for whatever comes out the other side. The result could be fun, boring, or just plain impossible—it’s often tough to predict, and that mystery is what makes the action continually engaging.

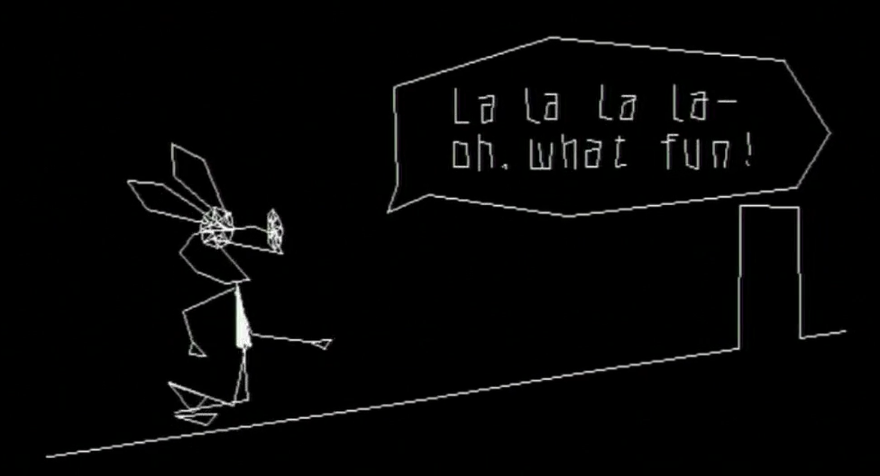

And in some ways, the quality of the results don’t even matter; the game is as much the act of generating levels as it is tapping buttons in time with handclaps. It’s weird and toy-like, and quite different even from genre sibling PaRappa, which followed a narrative filled with prescribed songs and characters. In contrast, Vib-Ribbon is just a Japanese-speaking rabbit stick figure trotting down an endless white line (not a drug reference). It comes from an era before post-release downloadable chapters and bonus multiplayer map packs. What you see is what you get, and in the case of Vib-Ribbon, there’s not much to it. The game’s entire replay value is contingent on what CDs its players happened to own.

Vib-Ribbon’s open-ended structure means that the overall value of the game is largely contingent on the extensiveness of one’s CD library, which many players never possessed, have gotten rid of, or packed away within the past 15 years. In addition to the European release of Vib-Ribbon, 2000 was also the peak year for music CD sales over the entire life of the format. Since 2000, CD market share has steadily dropped as digital formats have taken the reigns of the industry. That means every year since its launch, the viability of releasing Vib-Ribbon in a new region has become that much less potable. In fact, we only seem to have gotten Vib-Ribbon now out of some bizarre corporate guilt on the part of Sony, who touted the game at their E3 press conference seemingly ignorant to the fact that the country in which they were speaking never had access to it.

Morphing something physical into a digital experience.

And to those calling for an update of Vib-Ribbon that supports MP3s and other digital audio formats, more power to you, but doing so would fundamentally change the relationship between player, game, and music from the balance it currently strikes. The magic of Vib-Ribbon’s level generation comes from the transformative action of morphing something physical into a digital experience. The leap from MP3 to digital waveform is largely unremarkable in contrast, whereas the removing of one disc from the tray and locking in another takes on an almost ritualistic quality. Sacrifice disc 2 of Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness to the console and pray that it pleases the vector rodent gods.

The CD album format is ingrained into Vib-Ribbon’s DNA. In “Single Track” mode, you have to pick the numbered track you want to play without any identification beyond its numeric ordering value. The game assumes you have an intimate familiarity with your music in CD album format. This is how CD players circa 1999 worked, too, of course, never displaying artist names or song titles, only track numbers. It’s a distinction that sets the CD apart from other “album listening” formats such as vinyl or cassettes, which, while still arranging songs in a set order, place less emphasis on the easily skipped-to track number of the CD. To play Vib-Ribbon, you not only must have CDs, you must know CDs.

The result of this CD-centricity and as-is republication of Vib-Ribbon on PS3 is that it’s viewed primarily as a historical artifact, not a contemporary videogame. It’s been 3 weeks since Vib-Ribbon hit North American shores, but almost all chatter about it faded within 3 days after launch. Maybe that’s to be expected of any old game, but Vib-Ribbon was supposedly a cult sensation with a frothing demand for localization. Either the game simply didn’t live up to the legend or the technological parameters of playing it properly were out of reach or too inconvenient for most players (probably a bit of both). Thus, the lot of Vib-Ribbon as an artifact is to be owned instead of played. MoMA collected the game, and now so can you.

Ironically, Vib-Ribbon was originally released on a CD, too (a Playstation-formatted one), and with that form came rarity and mystique, or at least that was the view from here in the US. The digital release of Vib-Ribbon feels a bit like a game in captivity, removed from its natural environment and lured out into the open plane of some laggy LCD screen for all to examine. Sure it’s great that the game is more accessible than ever before, but what even is Vib-Ribbon in 2014 beyond some rabbit-eared Encino Man?

Vib-Ribbon still works, and gorgeously so.

The truth is that given the right conditions, Vib-Ribbon still works, and gorgeously so. I can’t recommend highly enough generating a level from Daft Punk’s Alive 1997, the electronic duo’s 45-minute, single-track live album from 2001. It’s the perfect balance of endurance and moment-to-moment challenge. The obstacles shift into slow motion whenever Daft Punk applies a flanger effect, and at several moments the choice and timing of the button prompts syncs up in a way that makes the level feel purposefully and beautifully designed instead of formulaically generated. The game enhances the album, creating a new physical experience with the music that is particularly resonant given the premise of the LP as a live performance of late-90s electronic music. Sure, “you had to be there” if you really want to be able to speak to the experience as it originally occurred, but at least there remains this document, a recreation of what took place, that bears its own artistic merit.

Vib-Ribbon is obsolete. Vib-Ribbon is essential.