If we can associate genres and aesthetics with film-makers (John Woo and action movies; Stanley Kubrick and deep focus) IO Interactive, especially in its prime between 2002 and 2007, was a game-maker defined by concerns about player agency. By constantly placing her in restrictive and alien environments, the Hitman series challenged the player’s typical experience of casual and unbridled progression. Kane and Lynch: Dead Men (2007), starring two legitimately unpleasant characters, undercut the prototypical videogame hero narrative—rather than saving the world, cast as a selfish villain, the player committed selfish acts and with selfish purpose.

“My name’s John Ford and I make Westerns,” once stated the director whose movies Stagecoach (1939) and The Searchers (1956) helped define a genre. It would have been less eloquent, and much less concise, but at the end of the 2000s, IO could have made a similar affirmation: “We’re IO Interactive and we want players to doubt themselves.” Of that intent, there is no better statement than Freedom Fighters (2003).

Rather than subvert the typical experiences of progression and control wholesale, Freedom Fighters hones in on videogames’ favorite tool, the one with which players most commonly exercise their agency: the gun. In a shooting game, the act of aiming and firing a weapon, usually, is made as simple and as clean as possible. One button to aim. One button to fire. One button to reload. If game-makers are concerned that violence in games has become, or always has been, blasé, they could do worse than re-evaluating their representation of firearms. That weapons can be operated and discharged so thoughtlessly in videogames is a root cause of their casual, indifferent treatment of violence.

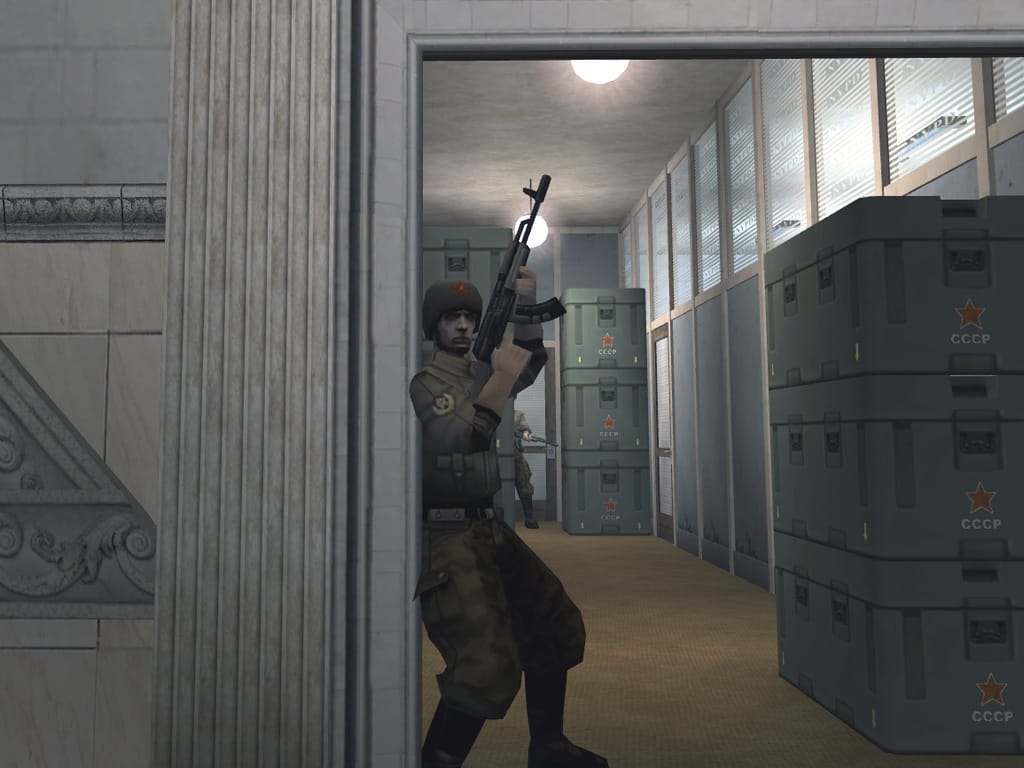

In Freedom Fighters, however, at least in its console form, aiming is perennially difficult. Rather than one of the controller’s shoulder buttons—L1 or L2, for example—the aim function is mapped to the right analogue stick, the same stick used to move the character. On paper, it sounds like a minor, perhaps undetectable difference. In practice, aiming in Freedom Fighters is always inconvenient. When the aim function is attached to the same stick used to move the character, aiming and moving at the same time, something which players are accustomed to doing almost unconsciously, becomes slow and arduous. The aiming reticule itself is unreliable. One may place it on an enemy soldier’s head, and fire, only to see the bullets hit the wall behind him. Put simply, guns in Freedom Fighters do not fire straight—a string of clean, successful kills is almost impossible to perform, and enemies don’t die from well-placed shots but a rain of abortive, inaccurate fire.

The Player’s own tools are not totally at her command.

It’s a tiny conceit, making the player aim with this button rather than that one, but with shooting in videogames so uniformly refined, even the slightest change can create a sense of unease. In Freedom Fighters, for once, the player is not a master of her weapon. It does not always do what she expects. She cannot kill with it, efficiently, 100 percent of the time. And suitably, she is playing not as a professional soldier but the freedom fighter. Christopher Stone, the lead character, is a plumber from New York City—his experience with AK-47s, one can presume, is limited, and so the weapon, for both him and the player, is unwieldy. This is still a game where generic enemies are killed, en masse, but where shooters typically permit players to feel wholly capable, and as if they are controlling similarly capable characters, Freedom Fighters subtly implies that even the player’s own tools are not totally at her command. Shooting is less predictable. As a result, it is performed less apathetically. Without any blood effects or hamstrung moralizing, a la Spec Ops: The Line (2012), Freedom Fighters encourages players to feel ill at ease during gunfights. Mapping aim to R3 is a simple flourish, deftly undercutting the player’s expected sense of absolute power.

As for Stone, he’s very much the stereotypical videogame hero. In its tackiest moments, Freedom Fighters sends Stone on a one-man mission to avenge his dead brother, and channels Mel Gibson’s Braveheart (1995) to lend him babyfaced charisma. But in other moments, he’s damaged—or at least physically affected—in a way that’s rare for videogame men. As Freedom Fighters progresses (the game is set in three acts: summer, autumn, and winter) Stone’s appearance grows more ragged. At the game’s beginning, he has short, cropped hair and tidy clean clothes. By the end, he’s unshaven, long-haired, and dressed in rags.

I’ve written before about the importance of depicting physical wounds on videogame characters—again, if violence in games is passé, it’s because games neglect to depict the consequences, be they big or small, of violence. Game heroes, regardless of their ordeals, tend to emerge unscathed. Nathan Drake’s hair remains perfect. Evie Frye’s dress stays unruffled. Master Chief remains safely encased inside his armor. Dirt and blood effects have changed this a little—I enjoy how Max bleeds and sweats in Max Payne 3 (2012)—but largely, today, and especially in 2003 when Freedom Fighters launched, the game hero was an impervious, implacable statue, an idol, in the pejorative sense. Where Kane and Lynch undermined the player’s sense of being a videogame hero by casting her as overtly unpleasant characters, Freedom Fighters does it by implying Stone’s vulnerability. As his battle against the Russian occupying forces becomes more brutal, his appearance grows more tired, more worn. Like switching the aim button to R3, it’s a minor device, but when compared to the men and women we’re used to playing in games, any suggestion of physical deterioration—any implication that fighting and killing is changing a character somehow—is a stark contrast. Stone is a hero, but unlike his videogame contemporaries, he inhabits that role at a personal cost.

But unlike his videogame contemporaries, he inhabits that role at a personal cost

Freedom Fighters doesn’t stop at challenging players’ sense of agency in videogames—it asks them to question their opinions on, what was at the time and in a broader sense remains today, an urgent real-world issue. It was released in September, 2003, six months after the bombing of al-Dora, which signaled the beginning of America’s ground invasion of Iraq. The day after the bombing, on March 20th, 2003, Gallup reported that 76 percent of interviewed Americans were in favor of the war in Iraq. Eight years later, as the final US troops left Iraq—and after more than 120,000 people had been killed—CNN reported that 68 percent of Americans opposed the war. 78 percent agreed that all troops should be removed, and the same amount believed that the US, if it remained in Iraq any longer, would not be able to achieve any more of its objectives. 22 percent believed America had succeeded at “most” of its goals.

Freedom Fighters didn’t predict a drop off of public support for the invasion of Iraq, but it certainly invited its players to doubt the war’s legitimacy—to empathize, perhaps more than the political rhetoric of the time would have encouraged, with Iraq’s people. Essentially, the game flipped reality on its head. In Freedom Fighters, it is Russia not America that is the world’s dominant superpower; America, not Iraq, that is under occupation. In the game’s opening level, Stone is forced to flee a cosy apartment by an attacking helicopter—he is literally driven from his home, and then forced to fight. The destroyed architecture you explore does not belong to the Empire State Building, the Statue of Liberty, or any of New York’s most famous landmarks. The levels are called “school,” “movie theater,” “hotel.” The destruction, rather than played for spectacle or cheap, sentimental appeal, is focused on more intimate locations, places familiar to people’s’ daily lives. As the US occupation hit full stride, Freedom Fighters asked its players “how would you feel is this were happening to you?” Its undermining of player agency in regards to mechanics and its player character is tied to this question.

Letting videogame players constantly be in control—to always hold the power—helps them to feel safe, comfortable, validated. Similarly, when George Bush asserted that “you can’t distinguish between Al Qaeda and Saddam [Hussein] when you talk about the war on terror,” it assured the public that their suspicions were correct, their support for war justifiable. Videogames, typically, convince the player of her own agency, her own rightness. The arguments for the war on Iraq, as presented in 2003, had the same effect on America. Freedom Fighters challenges both of these compacts, inviting the player to feel vulnerable and uncertain of herself and the American public to doubt its convictions about entering war. Where IO Interactive had previously subverted players’ mechanical agency in Hitman and would go on to overtly question their heroic state in Kane and Lynch, in Freedom Fighters the studio combined both and in doing so questioned a sense of self-assuredness its players would have likely had in real life.