Videogames and ’80s Hollywood Masculinity: A Love Story

That culture influences film is no big secret. Filmmakers often intentionally create films that reflect and affirm the beliefs of a given population, making it into a rallying point under which supporters of that film’s apparent beliefs flock. This is why Easy Rider is so embraced by anarchistic culture; why the hopeless romantic idolizes John Cusack in Say Anything (and later High Fidelity). Slackers love Kevin Smith and metaphysical thinkers dig Richard Linklater. Films reveal something about the cultural conditions under which they were cultivated. They operate, in short, as both mirrors and megaphones—reflecting culture while at once amplifying it.

Hollywood action-adventure films in particular have generally worked with ideas regarding representations of masculinity. Susan Jeffords’ Hard Bodies: Hollywood Masculinity in the Reagan Era is dedicated in its entirety to describing how masculinity is portrayed in Hollywood action-adventure films of the ’80s. In Jeffords’ words: “I chose to examine some of the most popular films—by box office figures—of the period precisely because their popularity must, I believe, indicate something about what kinds of stories mainstream audiences were interested in seeing, what characters they found compelling, and what images they found worth repeating.” She then derived the quintessential “model” hero of ’80s Hollywood, the ideal of masculinity that the audience members enjoyed viewing.

Films reveal something about the cultural conditions under which they were cultivated

Well, representations of masculinity also exist in another medium: Videogames. To explore this, first work with the assumption that film and videogames are in conversation with each other. At the very least, their sense of narrative and presentation work closely together. If film influences videogames, then film masculinity may be assumed to inspire videogame masculinity.

Yet games have not followed a linear pattern—it has not been a case of ’80s Hollywood masculinity inspiring ’80s games, ’90s Hollywood masculinity inspiring ’90s games, etc. Instead, the ’80s form of masculinity has stuck. It has not overtaken the popular masculine zeitgeist, rather overlapped or else fused with it to create a form unique to the gaming community. Masculinity in videogames is thus a mishmash of contemporary masculinity and decades-old machismo.

Let’s form an outline of the ’80s masculine ideal before connecting it to games. Susan Jeffords looks at films such as the Rambo trilogy, Die Hard and the early Lethal Weapon films to discover that this man is marked most acutely by his exterior presence. His “hard body” reveals “strength, labor, determination, loyalty, and courage” and is not “subject to disease, fatigue, or aging.” Take John McClane of Die Hard, for example. McClane is beaten and bloodied throughout the film—getting attacked by villain Hans Gruber’s henchmen, stepping on glass with his barefeet, falling from great heights, etc. Yet he manages to come out on top in the end, worse for wear but recoverable.

One of the key facets of Reagan-era masculinity is then defined by physical strength, being the best by taking out all the enemies. This leaves little room for issues such as post-traumatic stress, much less any strong emotion that leaves the man vulnerable. The Reagan-era man is a morally cut-and-dry figure, with clear delineation between good guys and bad guys. John Rambo exemplifies this. Rambo is a national symbol of toughness who “wins” his films by “defeating enemies through violent physical action.” The hero rarely feels bad for his foes, rarely feels regret in taking out his opponents. The ’80s man is purely focused on the task at hand with little regard for interpersonal pleasantries, not at all interested in reflecting upon the impact of his actions.

Now where do we see this in videogames? Moving chronologically, one can see it in various guises, nuances fluctuating, with that core of ’80s sensibilities remaining.

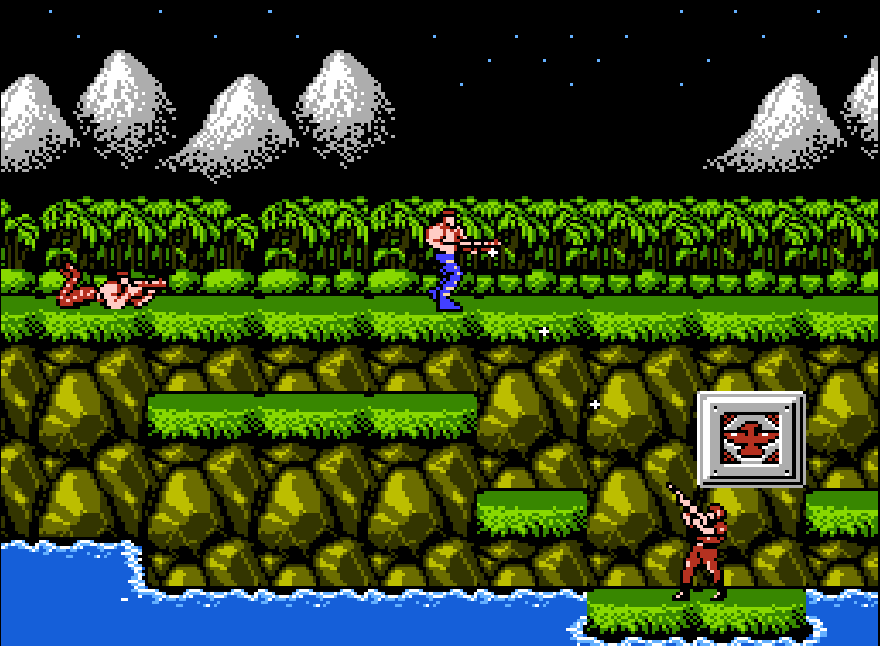

Late ’80s videogames reflect the ’80s ideals of masculinity through plot, player action, and a completely transparent lifting of images. This can be found in two representative examples: Metal Gear and Contra. Both released in 1987, both are thoroughly saturated with ’80s action film inspiration.

The ’80s man is not at all interested in reflecting upon the impact of his actions

Metal Gear concerns Solid Snake, part of the special forces unit FOXHOUND, assigned to infiltrate the mercenary state Outer Heaven in order to investigate possible weapons of mass destruction. (Hideo Kojima, Metal Gear‘s developer, has been consistently inspired by ’80s American cinema. The plot of Kojima’s first major adventure game release, Snatcher, is almost directly lifted from Blade Runner. His second, Policenauts, features a buddy cop dynamic and a horrible mullet similar to those of Lethal Weapon.) Contra approaches similar territory from a science-fiction perspective. It concerns two commandos named Bill Rizer and Lance Bean—clearly inspired by Rambo, with their muscles nearly bursting out of their shirts. Their mission is to take down the world domination-bent Red Falcon Organization. Note the emphasis on exterior threats, mercenaries, special government military units, and the catastrophic potential of powerful weaponry—all common trends in ’80s action films.

While there is a stealth angle to Metal Gear, both games still contain an impressive amount of killing. It is the primary focus, the determining factor in whether or not one may progress—how effective the player is at taking out these obstacles. Just as Rambo is remembered less for his story and characterization and more for his build and acts of physical prowess, so the protagonists of these games are distinguishable predominantly by their physical appearance and by what actions the player can make them do. These characters are muscled, weapon-toting men on the side of justice who defeat countless swarms of clearly delineated bad guys. The game demands that the player beat all these bad guys, or else lose all their health and receive a game over. The necessarily simplistic action allows for a clear binary between good and bad, much the same way that the simple thrills of their film inspirations do.

Moving forward, American masculinity in the ’90s was of two camps: One designated by its frustration and the other designated by its increasing sensitivity. This first is described as a “crisis of masculinity” in America by poet Robert Bly in his book Iron John: A Book About Men. Bly argues that the male gender in America has lost its grip on manhood, becoming increasingly emasculated in the modern world due to second-wave feminist influence. This frustration is an angry reaction, a somewhat nihilistic response to a world that lost touch with its past morals and virtues.

In the second camp, we see our Hollywood heroes shifting from the likes of Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger to Patrick Swayze and Steven Seagal. Muscled, tough, stoic heroes were replaced by sensitive men—though still tough, no doubt—who used violence sparingly and valued their mental wellbeing. Brenton J. Malin, in American Masculinity Under Clinton, outlines how the ’90s man ultimately took shape. The 90s man was no longer in touch with his whiteness, instead seeking spirituality from other sources such as east Asia and native America (See Dances With Wolves, The X-Files, On Deadly Ground). He is more in touch with his femininity. A newfound openness to different perspectives has removed the ’80s man’s rigid adherence to simplistic moral attitudes.

Now, videogames of the ’90s were somewhat informed by these new paths of masculinity, but they remain in many ways still within the grip of ’80s sensibilities. In the ’90s, American and American-inspired videogames did change somewhat, in terms of plot and underlying moral ideals, in ways that match this new masculinity. Yet certain key tenants of the ’80s form remain. Two examples dot either end of the decade: id Software’s Doom and Konami’s Metal Gear sequel Metal Gear Solid.

Doom has been hailed so consistently since its release in 1993 that it has been accepted into the Library of Congress for preservation as an important cultural artifact. Doom places the player into the shoes of an unnamed space marine, affectionately referred to by fans as “Doomguy,” and has you face off against hordes of hellspawn. This is, essentially, the plot. Doom manifests the ’90s masculine frustration by way of its nihilism. It is kill or be killed in the Doom universe—no moral high ground, no identity to speak of (aside from the player’s), no agenda to push. The demons are at the wrong end of the gun, delineated as evil by the fact that they want you dead. Their inhumanity absolves them of the sort of politics one sees in a Rambo film, in which humans kill humans. Doom sheds the already nuance-light ’80s masculine ethics and replaces it with an even simpler outlook—just shoot and keep moving. It is a demonstration of the frustrated ’90s man. With the last decade’s ethos gone, there is only wild abandon remaining.

Doom is a demonstration of the frustrated ’90s man

Yet Doom evidently admires one thing about the ’80s man: His physicality. In order to effectively play this game, one must overcome every enemy he faces without fail. Doomguy himself has the look of an ’80s hero, with bulking muscles and a constant look of anger and determination on his face. When injured in Doom, Doomguy’s avatar at the bottom of the screen will become increasingly bloodied. This ties into the “spectacle of pain” Jeffords identifies as characteristic of ’80s action films. The same underlying idealization of brute force and physical will exists here.

Metal Gear Solid, released in 1998, is also widely acknowledged as one of the greatest games of all time. As a ’90s game, it does feature some aspects at odds with the former era of masculinity. For instance, Snake does not manage to save the day entirely by the end. For all Snake’s strength, moral righteousness and intelligence, the plot reveals conspiracies far larger than he could ever hope to suppress, suggesting a smallness to his character previously discarded by ’80s action heroes, who inevitably fix up every loose end. Solid Snake’s physical prowess is offset by his increasing need for stealth and tactical intelligence, as opposed to the traditional run-and-gun method. This was a key component of the original Metal Gear, but the advancement of videogame technology allowed for a more refined version, one that actively discourages upfront violence.

This said, Solid Snake is in other ways still a posterboy for the ’80s masculine ideal. Take his personality, or lack thereof. Snake shares the ’80s male disdain for powerful emotions, opting instead for a sort of wry deadpan. Deep-voiced, rarely losing his cool, Snake always appears to be in control of himself. He is able to subdue the psychological attacks thrown at him by villain Psycho Mantis, whose twisted mind games brainwash Snake’s love interest and even break the fourth wall. Snake thus maintains physical as well as mental superiority.

This ’80s influence upon popular videogames continues on into the 2000s, managing to reveal itself both without much filter and in fusing with the anti-hero archetype that arose at the turn of the century.

This antihero archetype is what Brenton J. Malin dubs the “hypersensitive killer.” It arose with such TV shows as The Shield and The Sopranos. He is at once relentlessly immoral yet more in touch with his emotions than his peers, depicting the “extremely contradictory masculinity of the turn of the 21st century,” according to Malin. It is a variation on this man who finds himself at the center of one of the key videogame series of the 2000s.

The Grand Theft Auto series, beginning with its third entry and continuing to the present day, embraces the anti-hero craze of the ’00s. Grand Theft Auto III famously ditched the top-down style of the previous games, featuring a full city that players explored and destroyed at their will. You play as Claude, a strong, silent killer who gets involved in the criminal underworld of Liberty City, a thinly veiled recreation of New York City. His personality, or lack thereof, lends itself well to the ’80s mold. Little to nothing is known about his backstory. In an article released on Rockstar’s official website, the writers stated that they “just liked the idea of a strong, silent killer, who would be juxtaposed with all of these neurotic and verbose mobsters in an amusing way. He seems stronger and in control, while they seem weaker and frantic.” He is thus put on a pedestal above all other characters, in line with any given ’80s action hero. The game only drives this even further when the player is in control. In order to see the game through, the player must again be victorious in every violent confrontation.

The important, game-changing difference between Claude and Rambo is that Rockstar chose to ignore the ethical facet of ’80s masculinity. Claude is a fantastically immoral character. He shifts allegiance at will, performs hard and serious criminal work. He blackmails, murders and robs people. While these actions are in line with Malin’s hypersensitive killer (although we do not connect emotionally with Claude, we nevertheless are forced to identify with him as players controlling him), they are also in line with ’80s masculinity in that he is idealized by how impressively good at it he is. His ’00s-inspired anti-heroics are thus blended with ’80s masculine prowess.

The Grand Theft Auto series embraces the anti-hero craze of the ’00s

On the flip side of the morality scale, Bungie created the most prominent ’80s-inspired morally righteous hero of the ’00s: Halo‘s Master Chief. A cybernetically enhanced supersoldier, it is needless to say that Master Chief is a powerhouse to be reckoned with. As far as his personality goes, he is a Clint Eastwood-esque stoic—calm, cool, collected, tough as hell. He is largely emotionless, with few interpersonal relationships to speak of, and focuses purely on his professional life as a military weapon. This bespeaks of the ’80s masculine drive—a one-track minded individual who performs his job with the utmost grace, accomplishing whatever is thrown his way in the line of duty. This characterization comes closest to the ’80s form of masculinity in the modern era, with the only alteration being the post-millennial resurgence of pulp science fiction influence in the setting and story of the Halo series.

Videogame masculinity has overlapped with or else fused with the ’80s in interesting ways. It did away with moral codes, found instead a greater affinity for the anti-hero tendencies of popular television. It added other elements to videogames, such as conversation branches, stealth and more convoluted moral choices. But at their core, many popular videogames still share much in common with ’80s Hollywood masculinity. The general goal of killing or otherwise defeating one’s opponents to win is still widely adhered to. It is a trend, not a rule, but nevertheless a trend to which some of the most popular games of the last few decades have adhered to.

///

If you want more coverage on beef cakes, 80s masculinity, and videogames, back us on Kickstarter!