Videogames and the Art of Deception

The visual arts have a rich history of deception. Every painting that attempts to condense the world into two dimensions exploits flaws in the way our eyes work, fooling us into perceiving depth and distance through the use of vanishing points and skewed proportions. Optical illusions trick us into seeing differences in color that don’t exist, while portraits painted to look straight ahead seem to follow us as we walk past.

The advent of film and TV pushed the art of deception even further. Green screens convince us that the hero truly is dangling from the lip of a 60-storey skyscraper. Wire-fu, or the use of invisible wires to suspend actors in the air, allows punches and kicks to seemingly pack superhuman strength. And many of cinema’s greatest chase sequences only seem so frenetic because they were filmed slow then sped up in editing.

For as crafty as these techniques are, they simply laid the groundwork for the master of illusive media: videogames. In addition to packing the same tricks as movies and paintings, games are capable of entirely unique forms of deception that not only make their worlds feel more real, but highlight a level of ingenuity that rarely receives the praise it deserves.

games are capable of entirely unique forms of deception

Foremost among these deceptions is the illusion of virtual geography. Videogame worlds are typically too large to be loaded into a computer or console’s memory all at once. Instead, they are split into smaller chunks and streamed in on demand. This technique was especially common during the early days of 3D technology, when developers had to fight the hardware for every last polygon.

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time (1998) provides a great example. Scattered across the world of Hyrule are numerous holes Link can jump into, each of which leads to a small cave with various treasures to collect. Since the Nintendo 64 suffered from significant memory constraints, these caves could not be loaded into memory at the same time as the rest of Hyrule, and were instead lumped together on a separate map. When Link enters one of the caves, Hyrule is unloaded from memory and the cave map is swapped in.

While this allowed the humble N64 to support one of the largest virtual worlds of the time, it also paved the way for dedicated players to turn the deception back on the game. With a deft hand, Link can glitch through a cave’s walls and into the space beyond. There, the other caves stretch out like islands in a sea of black emptiness. By walking across the void to one of those caves, the player can trick the game into teleporting them back into Hyrule at a different spot to where they left it. Known as the Wrong Warp Glitch, speedrunners have used this technique to beat the game in mere minutes.

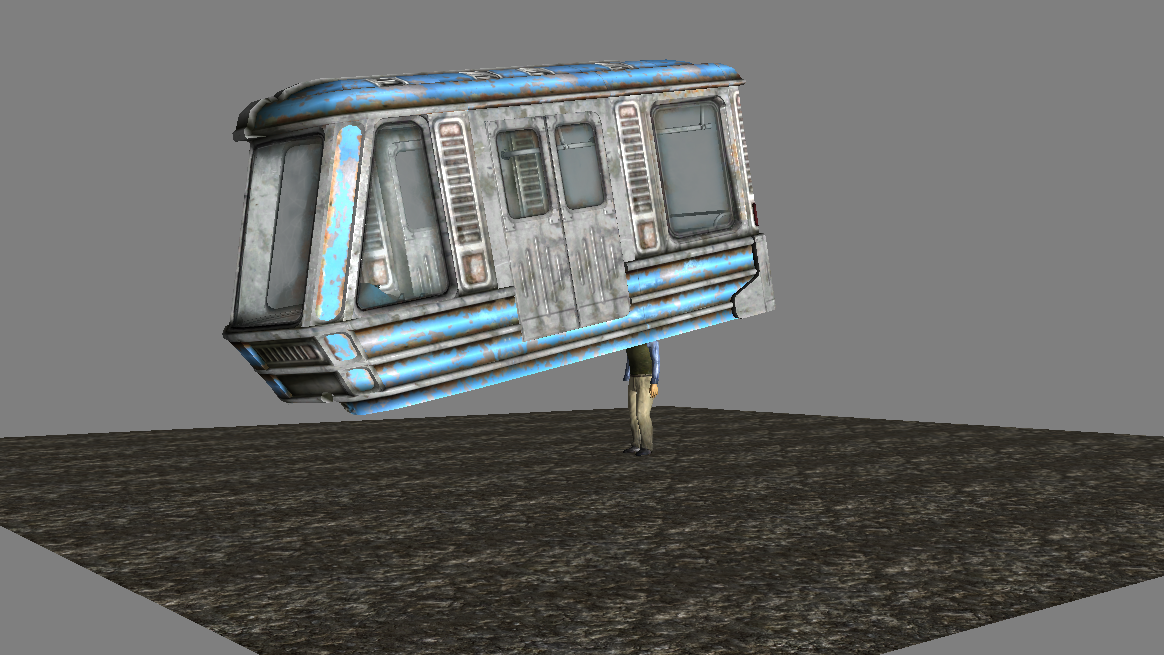

Despite the many advances of modern technology, today’s games still rely on deception to build their worlds. Fallout 3 (2008), for instance, pulls a fast one when shuttling players around its Metro rail system. Introduced in the game’s Broken Steel DLC, the game’s creators faced a big problem: Fallout 3‘s game engine had not been designed to support moving vehicles. Rather than completely rewrite the engine, then, the developers decided to get crafty. When the player flips the switch to start the train, the game briefly fades to white and equips the player character with what is effectively a train wristband. What ensues is a Flinstones-esque facade where the player character physically runs along the tracks beneath the train, dragging it with them, while the camera remains fixed inside the carriage. The whole sham is executed so perfectly, the player never suspects a thing.

Perhaps the most vital trick games pull on us is asset reuse. Where cartoons often loop background art and recycle animations to save time and money, games have the additional concern of minimizing the space they take up in memory and on disc. The original Super Mario Bros. (1985), for example, had to contend with the measly 2 KB of RAM available on the NES—for reference, the text of this article alone takes up over double that on today’s computers. To get around this limitation, Nintendo reduced the game’s art into small tiles that could be copied and combined on-the-fly to create entire levels.

Deception continues to course through the veins of videogames

This facilitated some clever sleight of hand: see those bushes Mario is running past? They’re just clouds colored green. Take a look at Luigi. He’s just Mario with a green top and white overalls. And the good ol’ Goomba? Not only was it the last enemy to be added to the game, there were so few bytes left that the developers could only afford two frames of animation. Goombas flip between these two mirror images to give the illusion of waddling. For a last-minute hack, the Goomba has done a bang-up job of introducing millions of players to the world of Mario.

Deception continues to course through the veins of videogames to this day. The recent global phenomenon that is Overwatch hides its trickiness right in plain sight. To emphasize the speed and power of its heroes, character animations do not stick to the laws of physics: when Pharah jumps, her head moves slower than the rest of her body, giving the illusion that her body is made of elastic; and when McRee reaches for his revolver, his arm turns temporarily boneless and whips across his chest with the swiftness of a cobra strike.

These animations look horrifying when slowed down, but in regular play, they occur too fast for our conscious minds to register. They don’t need to be noticed to have the desired effect, though. As part of Blizzard’s ‘squash and stretch’ approach to animation, the rubbery limbs lend a springiness to the characters that makes their actions feel smoother and more powerful. It’s a sly way of capturing the heroes’ superhuman nature without coming off as too cartoony or unrealistic. A talking gorilla we can accept, but a DJ with foot-long fingers might be a bit much.

The art of deception is a vital component of videogames. It lets us suspend our regular lives and escape into worlds that feel just as real and dynamic, even when they’re just crude simulacrums at their core. We want games to lie to us because the lie is more entertaining than the truth. Like fad diets and billion-dollar lotteries, we want to believe the fantasy can be real.

Header image via Gabriel Rojas Hruska