Virtual Light: Exploring In-Game Photography And Photo History

This article was written by Eron Rauch and originally published on videogametourism.at. You can find more of his writing and artwork through his blog and portfolio.

It was brought to us by our friends at Critical Distance, who find the best in critical writing about games each week. You can see more at their site, and support them on Patreon.

///

If you are anything like me, you had friends who linked Rainer’s “The Art of in-game Photography.” If you are anything like me, you saw many of your friends duke it out on Facebook and Twitter over whether or not this was a legitimate art — whether it was even photography.

The arguments, if I may dramatize them like a cheap real-crime TV program, went something like this: It’s photography. No, it’s not photography. Yes it is. No it isn’t. Uh-huh. Nuh-uh. Your mother’s not photography. Well your mother was photography last night.

Then: You own the image. No you don’t own the image. Yes it is. No it isn’t. Uh-huh. Nuh-uh. I own your mother. Well I owned your mother last night.

I have spent too much time drinking coffee and waiting in lobbies in League of Legends (to inevitably have the 5th PUG pick Feeder-Yi). I spent this time mulling over why this video-game-photography-thinger gets people so worked up. Here are two thoughts:

1) Both sides of these arguments seem to have good points.

2) What sides? The history of photography is way too weird for binaries.

The more I turned these two ideas around the more it occurred to me that they were related. Additionally, the more I pondered the original article on In-Game Photography (IGP) and the very polarized reactions it elicited, the more I grew adamant that these strong reactions mean that this subject is a very important notion to ponder and hence make art about.

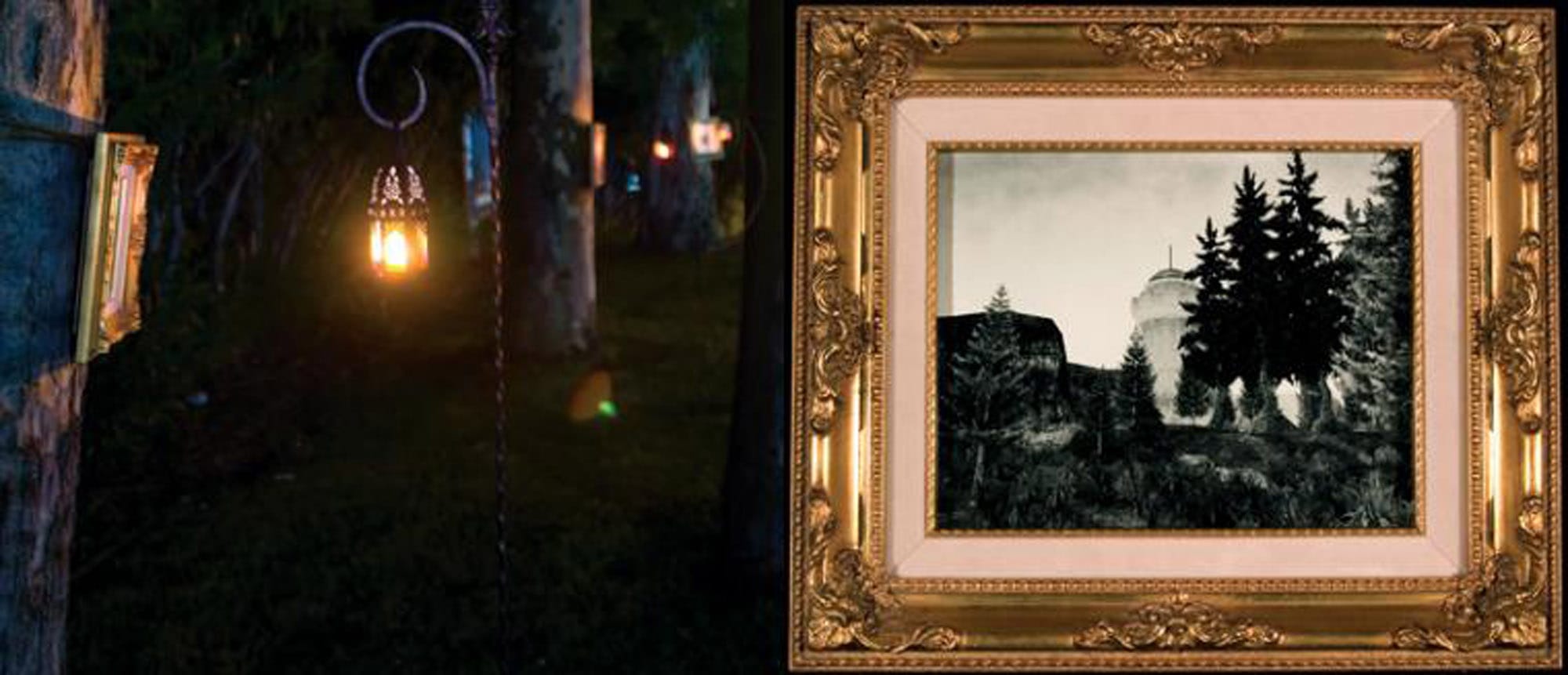

Eron Rauch, “A Land to Die In (Arrival of Dusk)” Outdoors Installation Detail fom A Land to Die In

Two sides

First I should back up and introduce myself. I am a full time artist living in Los Angeles. I have had numerous gallery shows, given lectures at schools and written articles for academic journals. I have both an undergraduate and graduate degree in photography as well and the student loans to prove it. I’ve also been a long-time gamer. As such, I’m hyper-aware that both sides have strong points, as do so many of the other voices joining this growing conversation about IGP (and the broader realm of what I would call “virtual photography”). In fact my work, which deals with and uses videogames, has left me squeezed between intelligent opinions on both sides.

On one side, many of my friends in LA are in the game industry and are understandably protective of the assets they develop. They are artists in their own right and spend tens of thousands of hours making this stuff. So, as I sip my coffee and pray that the final team pick isn’t a Yi, I find it is very reasonable that my dev friends might get a little bit defensive when an IGP practitioner claims they “own” an image because the gamer pressed F12. After all the “photograph” was made facing a scene that the designers had slept under their desk for a month to make. Also, I should note, with droll understatement, that people in the videogame industry are sometimes a bit busy and thus it is unsurprising that they don’t have lots of time to dedicate to the vagrancies of the fine art world.

The history of photography is way too weird for binaries

On the other side, many of the rest of my friends are from the art world. The art world is a strange place filled with very dedicated people that spend tens of thousands of hours making works of art. As such it’s quite reasonable that artists get a bit defensive when someone comes along and says they made/own “art” because they pushed F12 in an explosion-and-T&A filled entertainment product that made a hundred million dollars. Also, I should note that they often are so busy without many prospects for making much money so they don’t really have the time or inclination to play videogames and are old enough that they have no hands-on experience with videogames.

Given all of this, you might be able to imagine the deeply furrowed brows that challenged me on every side when I told my friends and teachers in grad school that I was doing a photography project based on the virtual worlds of WoW and other MMOs.

Eron Rauch, “Entering Combat” from A Land to Die In

Virtual light

In the couple of years that it took to make the artworks for my WoW show I became the warlock class officer in a solid Black Temple/Sunwell raiding guild with 1800+ ranked PvP team. This was hardly my first deep game experience — by 18 I had spent plenty time in MUDs and 4X games, Dragon Quests and Final Fantasies, Mechwarriors and Elder Scrolls.

One of the interesting quirks of being trapped in the middle of these two arguments is that the pressure can often result in an accidental diamond.

In this case, I was in my studio drinking with friends and ranting about how neither side had all the answers. I was so pissed off at being misunderstood by both sides, that something just popped out of my mouth, “Photography wasn’t even considered art by most people for like 100 years, so dammit, 100 years from now I’ll bet screenshots from videogames will be in the Getty!”

The realization that the current debate about IGP (and virtual photography) is as much of an intellectual wilderness as the early days of analog photography has informed my thinking long after the hangover faded away.

In fact, what makes IGP/virtual photography interesting is that this seemingly “new” space for art is recreating similar arguments from the early history of photography. Then as now, the various genres and uses of imagery are like a friend’s relationship status: “It’s Complicated.”

First, some history

So let’s take a quick look at the early days of photography and scry that history for some ideas about the future of IGP.

Photography as we know it was invented in the 1830s. Yet, it wasn’t until nearly 1930 that the Met became one of the first art museums in the world to have a specialized art photography department, despite the prevailing opinions of the rest of the art world. It wasn’t until the early 1970s that there was widespread acceptance of art galleries that specialized in selling photography.

Photography wasn’t even considered art by most people for 100 years

So what were people doing with photography for that whole previous century if they weren’t sure if it was art? I know I’m being facetious, but the question begs a number of interesting followup-questions which directly inform what is happening now with IGP and virtual photography: Why do people make photographs? Who makes photographs? What kinds of photographs get made? What does photography mean in the internet age?

Well, let’s run through a few of the major historical veins of photography to see what they might teach us about talking about a broadened pallet of types of IGP. These aren’t absolute categories, in fact many photographs can be part of more than one category or even change categories as they age (such as the military survey photos of the uncolonized American West now being shown as art in the Getty).

Let’s talk about four categories. We’ll call these photography divisions “Art”, “Amateur,” “Artisan,” and “Vernacular.”

“Vernacular” photography is the category in which an overwhelming percentage of all photographs fall. I can’t find hard numbers, but 99.9% of all photographs made to date is assuredly an understatement.

This kind of photography encompasses: pictures of your cat; a photo of your dad catching a fish in Florida; your friend sticking his head through the stocks at Medieval Times; an image of of the Eiffel tower you shot with a disposable camera on your honeymoon with your second wife; the picture of your used PS1 that you’re selling on eBay; or even a snapshot of the dent in your car you sent your Mom after an accident.

No one is claiming these images are art, no one is claiming that the subjects of these images are “theirs.” Those sorts of higher order questions are so far from the intended use of these images that you may as well be comparing your grocery list to Shakespeare sonets.

What would “Vernacular” look like with regards to IGP? Screenshots of your guild’s first Kel’Thas kill; that League of Legends score card where you have six wins in a row on Irealia; A pic of that giant wall near the one functional dungeon from GW2 beta; a cool dragon from Skyrim. In short, a vast majority of all the screenshots made.

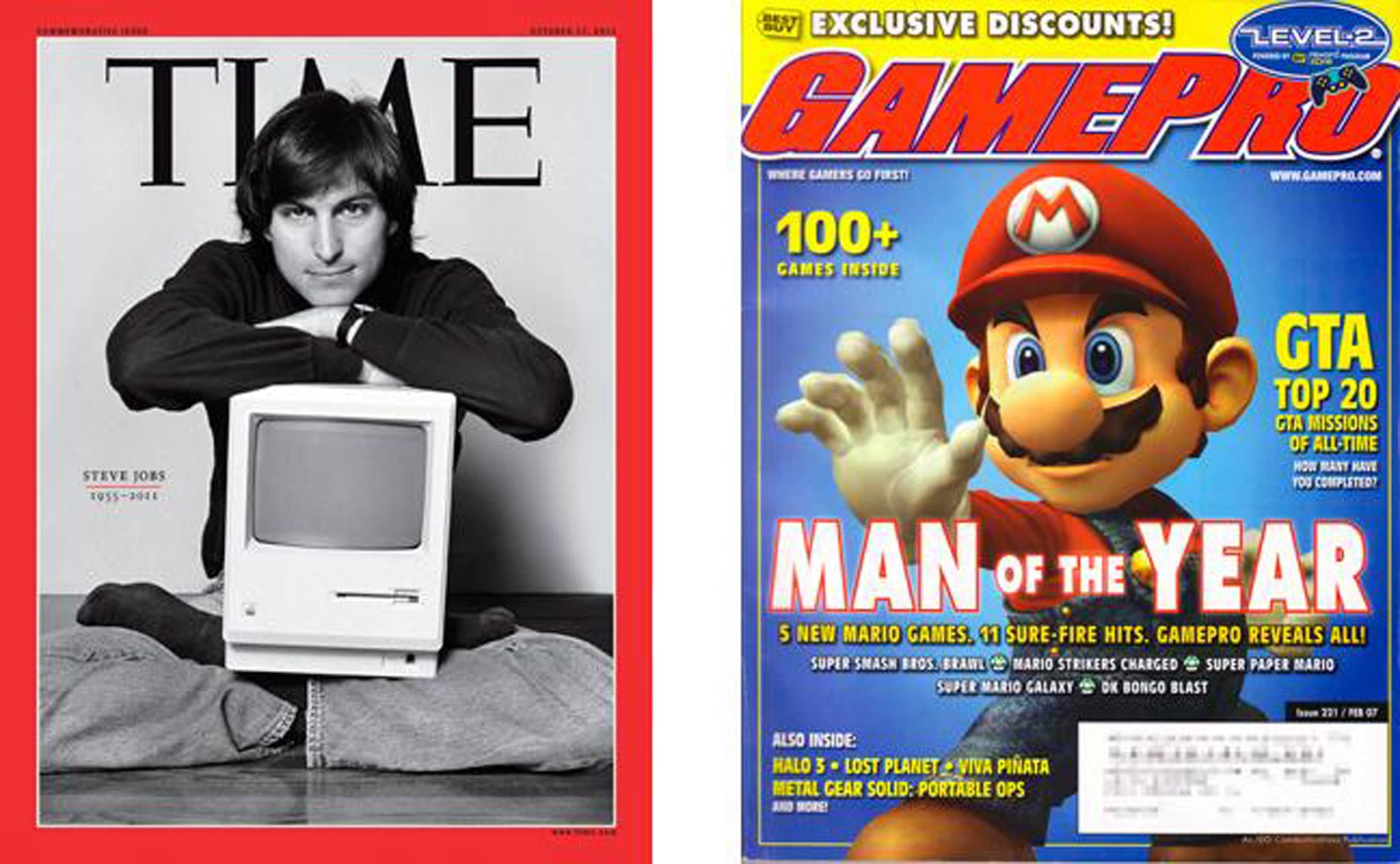

“Artisan” photography is probably the second most prevalent kind of photography. This is work made for commercial purposes by skilled laborers. From billboards to Pizza Hut advertisements; from the pictures of Amazon items to high school portraits; from a poster of your favorite athlete to postcard of Hawaii.

If you try to ignore the commercial intent of “Artisan” photographs and try to judge it as “Art” or “Not Art” you would be completely missing the point. It would be the same as going to Home Depot and looking at a hammer and trying to talk about it like a sculpture in an art museum.

Now let’s try to imagine what kind of work “Artisan” imagery might be in IGP terms: Look at an issue of IGN and you’ll see rampant examples of this kind of photography illustrating all of their articles. Also look at the back of any game game boxes you have around. Those featured micro-transaction ads in Steam are just another form of product photography.

To understand “Amateur” photography, which is an even smaller subset of photography than “Artisan”, we need to let go of the current negative associations of the word amateur.

Traditionally it doesn’t mean “noob,” instead it means, “someone who does something because they love it, not for money.” Most of the great early photographers, including the English gentleman who invented the negative process, Henry Fox Talbot, fall under this category.

“Amateur” photography isn’t even made to be shown in a gallery context, though it might end up there. Instead it’s made simply because the photographer wants to make it. It’s a hobbyist approach. It’s Popular Photography. It’s dramatically-lit sexy ladies. It’s people who cosplay and stage elaborate shoots in character. It’s guys that are dentists who buy huge lenses and travel to Antarctica to shoot pictures of penguins. It’s about skill, fun and beauty.

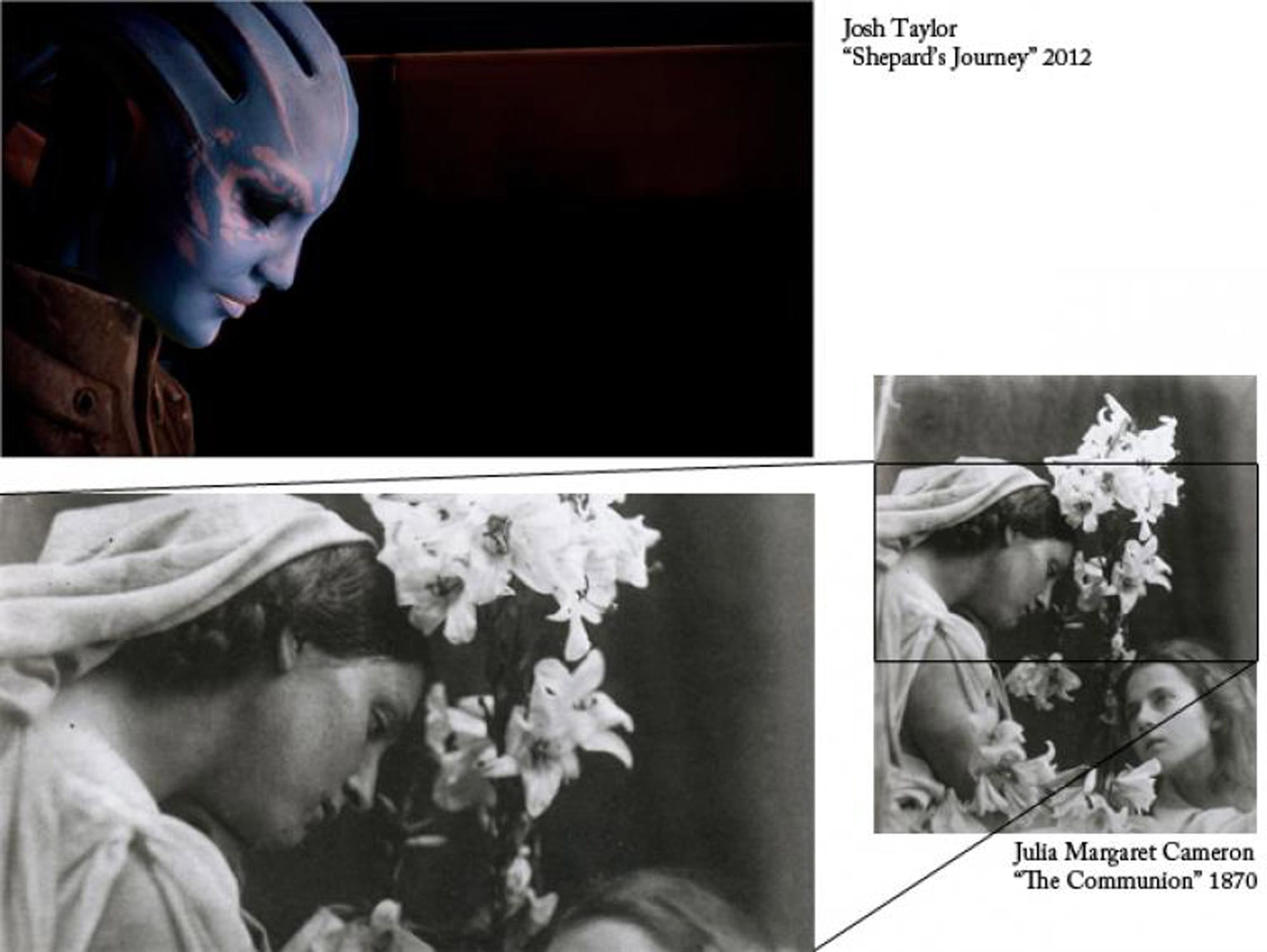

Look at the work of Julia Margaret Cameron, who had her and her friends dress up as Biblical and mythological characters. Her work feels interestingly similar to machinima to me. Some “Amateur” work will end up as being categorized as art years after it was made, but this shift is usually owing to outside influences and changing opinions in the art world, not the intention of the original practitioner. But like a life-long dedicated home cook, the work of the amateur is primarily made for personal enjoyment.

This “Amateur” approach is the edge where most of the photographers who were featured in the original IGP post on this site inhabit. Amateur is a primarily self-defined category. So if you have a blog or Tumblr dedicated to your screenshots, or have submitted work to a screenshot/IGP contest you’re probably in this category. Do you want to make the coolest images you can? Absolutely. But are you actively trying to create a body of work that will be displayed as a post-mortem retrospective at the Louvre in 100 years? Probably not.

Art Photography

Finally, at the tiniest tip of the photographic iceberg, you have “Art.” This isn’t a quality judgement, just that there are by far the fewest number of images produced in this category than any other.

This is work made with the intention of participating in the contemporary and historical art conversation. This is, regardless of your opinion about its quality, the work of Robert Frank, Cindy Sherman, Daido Moriyama, Henry Wessel, Lee Friedlander or Thomas Struth.

I am a firm believer that anything can be art, but once you label it as such, like putting a boat in the middle of the ocean in a terrible storm, you open the work to the full deluge and turmoil of all of art theory and criticism.

The difference between “Amateur” and “Art” is the difference between your friend who is a lawyer, but can strum out some cool covers of Radiohead at a party (an amateur, no matter how talented) and your friend who writes and performs with a band for the last five years, has three albums and is working on booking their first tour (a professional artist, no matter how untalented). Admittedly, this is a fine line that can often be crossed in both directions, or in the case of blues musicians or semi-outsider artists like Van Gogh, can be either depending on the era.

To get your brain-meats churning a bit more, a couple of other categories that I skipped over would include photojournalism (think of the blog coverage of the pink-haired Gnome riots in WoW or the recent economic assault in Eve Online), evidentiary (bug reports), schematic (documents passed during the development process), and strategic (virtual war, like in Cyberpunk novels). Categories are always a bit arbitrary and mutable, so the debate over the use of any category is always part of the conversation!

New tools for discussion

The whole reason that I wanted to write this article is so that we can talk about IGP in a more useful and sophisticated way. After all, a reviewer wouldn’t apply the same criteria for success for an FPS and a 4X game, or even at an extreme dealing with computers, for MS Excel and a Video Game. It would be equally a mistake to analyze all the different kinds of photographs, whether they are IGP, virtual or analog, the same way.

Each IGP version of these categories will of course borrow, steal and comment on the discoveries of other categories just as they have in the history of analog photography. That’s part of the fun of this conversation!

Next time you’re arguing with your friends on Facebook or at a bar about IGP, try to think about why the specific image your are talking about was made and what its intended use and audience might be. Whether you’re talking about IGP or analog photography, you’ll be amazed at how much better the conversation goes when you pay attention to the context of the image.

By using these more sophisticated tools for conversation, those of us who are interested in IGP and virtual photography can prove how vital our field is to the broader conversation about art, photography and life. We can get further than “Yes It Is / No It’s Not” by treating the realm of video games and virtual photography as they are: sophisticated, nuanced and complex topics that sometimes tell us boring things, or show us pretty things, and can also convey deep truths about our complicated virtual modern lives.

///

This article was written by Eron Rauch and originally published on videogametourism.at. You can find more of his writing and artwork through his blog and portfolio.

It was brought to us by our friends at Critical Distance, who find the best in critical writing about games each week. You can see more at their site, and support them on Patreon.