Visions of hell: Dark Souls’s cultural heritage

It’s the trees; the twisted, whorled trees, their skeletal branches raking the belly of the looming sky. Those are Caspar David Friedrich trees, unmistakably corkscrewed and bent. They rise out of collapsing stonework just like Friedrich’s do, and are touched by the same fading light, decapitated by the same dusk shadow. They crowd like pious pilgrims around ruined churches and abbeys, as if, like Friedreich’s painted forests, they were about to pull those ruins to the ground. Perhaps a few branches are woven here or there between the stone work. Getting a purchase, working their way through a century-long demolition, an inch at a time. Not that these trees, or Friedrich’s trees are moving—they are frozen, locked in rigor mortis, clawed into the dirt and stone like the hands of an eternally dying man, scrabbling for his savior. These are Dark Souls 3’s trees, and they are, among a thousand other things, marks of a certain history.

The German Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich is the kind of figure that is hard to escape. His influence describes a wide field of images and imaginings that stretch out from his paintings like roots set in frozen ground. In the early years of the 19th century he depicted landscapes punctuated by decaying ruins, images that were bleak and melancholy and reached towards the metaphysical, the sublime. Though his painting Abtei im Eichwald (“Abbey in the Oak Forest”) might appear now like a collection of horror cliches—its procession of shadowy hooded figures within a graveyard, towered over by an empty stained glass window and those skeletal trees—it was instead a pursuit of the spiritual, of the spaces of transience that might open up once we passed through the portal of death. It is a work that imagines our end, both as individuals and a whole, and the beauty in that truth.

Caspar David Friedrich, Abbey in the Oak Forest. 1809-1810

Dark Souls 3 is full of ends, though it might not be the end of the series. Its central thematic image is of fading embers—life dying out in a slow and sustained crawl. In its world, once great dragons turn to ash in the wind, pilgrims lie on the road where they fall, and even great warriors have turned against their own, fighting themselves in steadily decaying battles. It’s a fitting conclusion for a set of games marked by seemingly endless decay. Our first steps into this world in Dark Souls (2011) were as a deathless hollow, imprisoned to await the end of the world. Dark Souls 2 (2014) continued the trend, placing us in a kingdom whose very king wandered his own crypt in circles, like a restless sleeper. And though it might have been used as a brash marketing tool, the original “prepare to die” slogan might be recast as an existential statement of biblical proportions, a metaphysical challenge. After all, can one ever be truly prepared for death? In Dark Souls we realize that fallacy—the player never truly dies, only prepares endlessly.

a love of the macabre that goes beyond the reverence of romanticism

For Dark Souls 3 to turn so decisively towards the romantic influences of the series, where man is a fading figure in a landscape of natural processes of erasure, makes for a satisfyingly logical turn. It’s not only the sudden influx of crooked trees, growing from every ruin: the game even seems to explicitly reference what is Friedrich’s most recognizable painting, Der Wanderer über dem Nebelmeer (“Wanderer above the Sea of Fog”), with a single hollow standing on an outcrop above a similarly mist-bound landscape. Friedrich’s Wanderer is generally thought to represent introspection and a sense of the uncertain future that faces each of us. That Dark Souls 3 might remake the image with a deathless hollow at its center perhaps carries a sense of irony—the future in question being only an endless cycle of death after death, the metaphysical plane of peace and salvation remaining forever distant and unknown. Yet can such a line be drawn between a 19th century German romantic painter and a videogame of the new millennium? Can the influence be true across all those epochs, reaching forward or back past so many years? No, like Friedrich’s trees, the true path is far more twisted and whorled than that.

///

Dark Souls, as a series, is never as somber as I remember it. Think of the skeletons. They jig from foot to foot, scimitar and shield in hand, like Harryhausen intended. And when they build themselves up from a pile of bones, they pick up their own skull and neatly place it atop their shoulders like Jack Skellington himself. Not that they aren’t terrifying in their ceaseless pursuit of the player, but they betray a certain kind of joyful horror, a love of the macabre that goes beyond the reverence of romanticism. Even High Lord Wolnir of Dark Souls 3, surely the peak of the series’ skeleton crew, seems to rattle his bones in a jingle-jangle way, his jaw hanging open in a perverse facsimile of a smile. But to place Wolnir and his kin entirely in thrall of these influences would be wrong. Dark Soul’s skeletons are not just the Children of Hydra’s Teeth, or warriors from Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Triumph of Death, they are Gashadokuro.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861), Mitsukuni defying the skeleton specter invoked by princess Takiyasha

Gashadokuro are giant skeletons, formed from the gathered bones of the dead. Part of Japan’s rich folklore of yōkai—supernatural beings that haunt or help humans—Dark Souls’s skeletons of all sizes emanate from these tales, much like many of the other demons and monsters that make up the bizarre, alluring and terrifying pantheon of the series’ enemies. To talk of Dark Souls bestiary without talking of yōkai is to miss its true origin. It’s not that every one of Dark Souls’s enemies can be traced directly back to a specific yōkai, it is that all of them are crafted in the spirit of these creatures. This spirit finds perverse enjoyment in the weird and the supernatural, a sense of joy in the tricks of the dead and the demons of this world.

There is no better illustrator of yōkai than Utagawa Kuniyoshi. His Ukiyo-e woodblock prints, like Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre (pictured above), play on the grotesque and the spiritual, reaching deep into popular Japanese folklore. His fingerprints are all over the world of Dark Souls. When you see the summoned skeleton leaning up out of the void in Kuniyoshi’s print, it’s not hard to imagine Wolnir’s ornate bracelets draped over its forearms, or golden crown sitting atop his head. Kuniyoshi was a master in his own time, perhaps one of the greatest printmakers of 19th century Japan. Eager to learn from both classical Japanese methods and a new influx of Western art, his work became known for its imagination and supernatural flair. Limited by strict censorship, he used monsters, demons, and spirits as a way to make hooded statements about the culture he saw around him. A non-conformist within a traditional form, his popularity was ensured by the a growing interest in the macabre in a rapidly modernizing Japan.

To find the ultimate Kuniyoshi creature in Dark Souls you might turn to the game’s humble Mimic. A tradition that stretches back to Dungeons & Dragons original 1977 “Monster Manual”, these sentient treasure chests have been embraced by Japanese games for decades. Yet Dark Souls’s mimic stands high above them all, with its repulsive lolling tongue and distended, emaciated body. Once disturbed, these comical monstrosities strut around like a cross between a clown in a Kabuki comedy and Buster Keaton, their prime attack a slapstick kick. Watching them, I can’t help but think of Kuniyoshi’s series of prints depicting monsters performing samurai plays; semi-satirical images filled with personified objects and bug-eyed freaks. It takes only a small leap of the imagination to place a gambolling Mimic among them, gurning from behind a paper screen.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi, The Monster’s Chushingura, 1839-1842

It is this cavalcade of grotesque creatures that brings life to the otherwise dead and dying world of Dark Souls. Again and again the series finds delight in its perverse creature designs—from the pop-eyed froggy Basilisks to the deformed and oh-so-white eyes of the troubling Wretch. Even in its darkest moments, the series presents an unhinged goofiness that has spread to its fans. It’s this that feels like a distinctly Japanese sensibility of its art history; a tribute to the tricksters and freaks of folklore. That attitude connects clearly to a history that has the work of Kuniyoshi at its center, producing print after print of the mystical and the comical, to fill the walls and bookcases of 19th century Japanese homes. Yet at the same time, that Kuniyoshi’s prints of yōkai were gaining popularity in Japan, another of Dark Souls’s great influences was in the early stages of his career half a world away.

///

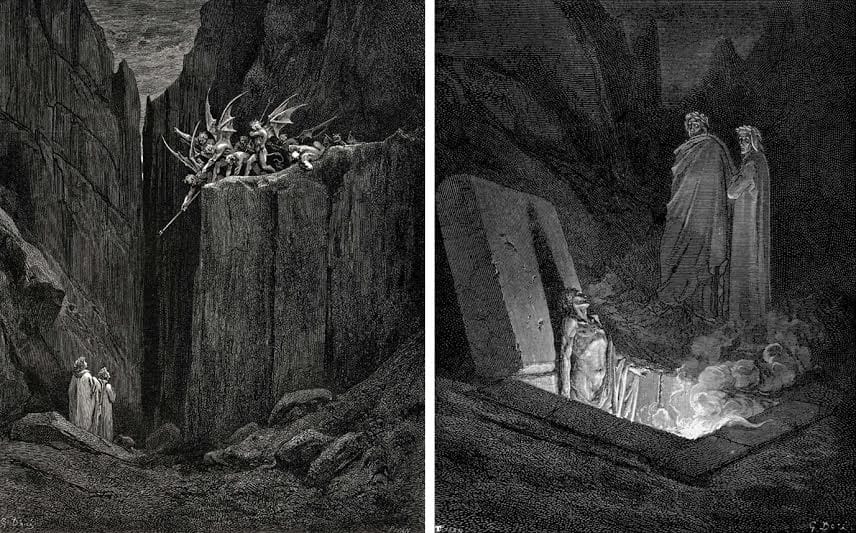

It’s hard to place a finger on the most recognizable reference to Gustave Doré’s incredible illustrations in the Dark Souls series. The artist, who in a short 50 year life span produced over 100,000 pieces, and illustrated many of the great works of world literature, haunts many a crooked corner of Lordran, Drangleic, and Lothric. Flicking through his illustrations for Dante Alighieri’s great masterwork The Divine Comedy (1320), it is impossible not to be reminded of the landscapes and demons of Dark Souls. On top of a sheer rock wall we see a clutch of figures, huddled like the Deacons of the Dark. In a shallow pool lie piles of corpses, twisted into an inseparable mess, like the horrible sights that await in the drained ruins of New Londo. The great king Nimrod chained, now a giant and no longer a man, echoes the lost ruler of Drangleic. It is no surprise that it is the first book of The Divine Comedy, Inferno, depicting Dante’s journey through hell, that brings us these images. Doré’s bleak, stony, and understated depictions of Satan’s kingdom so strongly contrasted with decades of medieval hellfire that had gone before. They are powerfully mythic images, ones that have been reached for again and again by artists in search of the power of the dark.

the concepts of loss, despair, and the allure of the occult

Though iconic now, the success of Inferno was never assured. Many of Doré’s supporters called it too ambitious and too expensive a project, and so, in 1861, driven by his passion for the source material he funded its publication himself. His risk paid off, and the volume and its subsequent sister volumes Purgatorio and Paradiso, depicting purgatory and Heaven respectively, became his most notable works. A critic at the time of its publication wrote that the illustrations were so powerful that both Dante and Doré must have been “communicating by occult and solemn conversations the secret of this Hell plowed by their souls, traveled, explored by them in every sense.” This plumbing of the depths of despair in search of beauty is the true thematic link between these illustrations and Dark Souls art. Like the monsters of Kuniyoshi, in Doré we don’t just see the aesthetic roots of Dark Souls, we see its themes—the concepts of loss, despair, and the allure of the occult sketched out in chiaroscuro black-and-white.

Gustave Doré’s (1832-1883), illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy

As well as being the year Inferno was first published, 1861 was also the year Kuniyoshi died. In his final years, he had trained Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, an exceptional artist in his own right, who would become the last master of the Ukiyo-e woodcut tradition. Both Doré and Kuniyoshi were working at the end of their own traditions, and within decades of their deaths, woodcuts and wood engraving would be replaced by lithographic and photographic techniques. Both artists were childhood prodigies and, though they never met, there is a certain underlying synergy between their work. Not only did they both make their names depicting a powerful mix of the modern and the supernatural, they both were populists, their works not designed to be hung on gallery walls, but to be collected in books, placed in homes, to terrify and delight the population. This, along with both artists’ incredible volume of work, is perhaps one of the secrets to their lasting influence—they didn’t court the academy or the critics, they instead captured the imagination of a whole generation within their respective cultures. This connection may have never manifested in their lifetimes, but in the Dark Souls series we can begin to see its power. Yet, From Software’s games were not the first to connect these Eastern and Western traditions in pursuit of the fantastic, and it is at their meeting point that we find the most direct of all Dark Souls’s influences.

///

An absurd greatsword, so huge it can barely be lifted. An army of demons, grotesquely mutated, stalking a medieval landscape. Knights, dressed in ornate armor, hammering each other in swift and bloody combat. After reading Berserk it is impossible to return to Dark Souls without the adventures of Guts in mind. Kentaro Miura’s manga, first published in 1989, is like a blueprint for many of Dark Souls’s most distinctive pieces of design. It’s a connection that ranges from the general to the specific, with many armor designs, weapons, and enemies riffing off Berserk directly. Bosses like the iconic Ornstein and Smough look like they might have walked off the pages of Berserk’s first volume, while the Darkwraith Armor, Balder Armor, Dragonslayer Armor, and the Armor of Artorias are all tribute pieces to Miura’s work. But more than that, Berserk represents a twinning of Eastern and Western artistic traditions that finds its successor in the distinct art of Dark Souls.

Panel from Berserk, Vol. 1 (1990)

There is nothing subtle about Berserk at first glance. Pulpy to the extreme, its pages are a patchwork of sex and violence, drawn with a flair for sweeping swords and fountains of blood. Guts, possessed by an evil spirit and missing a hand, most obviously brings to mind Ash from Sam Raimi’s Evil Dead (1981). Meanwhile, the wandering swordsman plot is a classically Japanese story, taken from legends of Samurai and Ronin. Berserk’s world, however, is distinctly Western, taking place in a fictional version of medieval Europe, albeit one overrun with demons. It is this setting that hints at the inspirations underlying Miura’s stark artwork—a rich vein of gothic, romantic fantasy art that runs through the manga, some of it reaching back hundreds of years. Doré is more than present, having come to Miura through one of his heroes Go Nagai. Inspired by a Japanese edition of Doré’s The Divine Comedy given to him as a child, Nagai created Demon Lord Dante, a manga which would become the popular Devilman. Miura found both the Western mythology and the dynamic art of Berserk in Nagai’s work, pushing it to violent extremes in his own energetic linework.

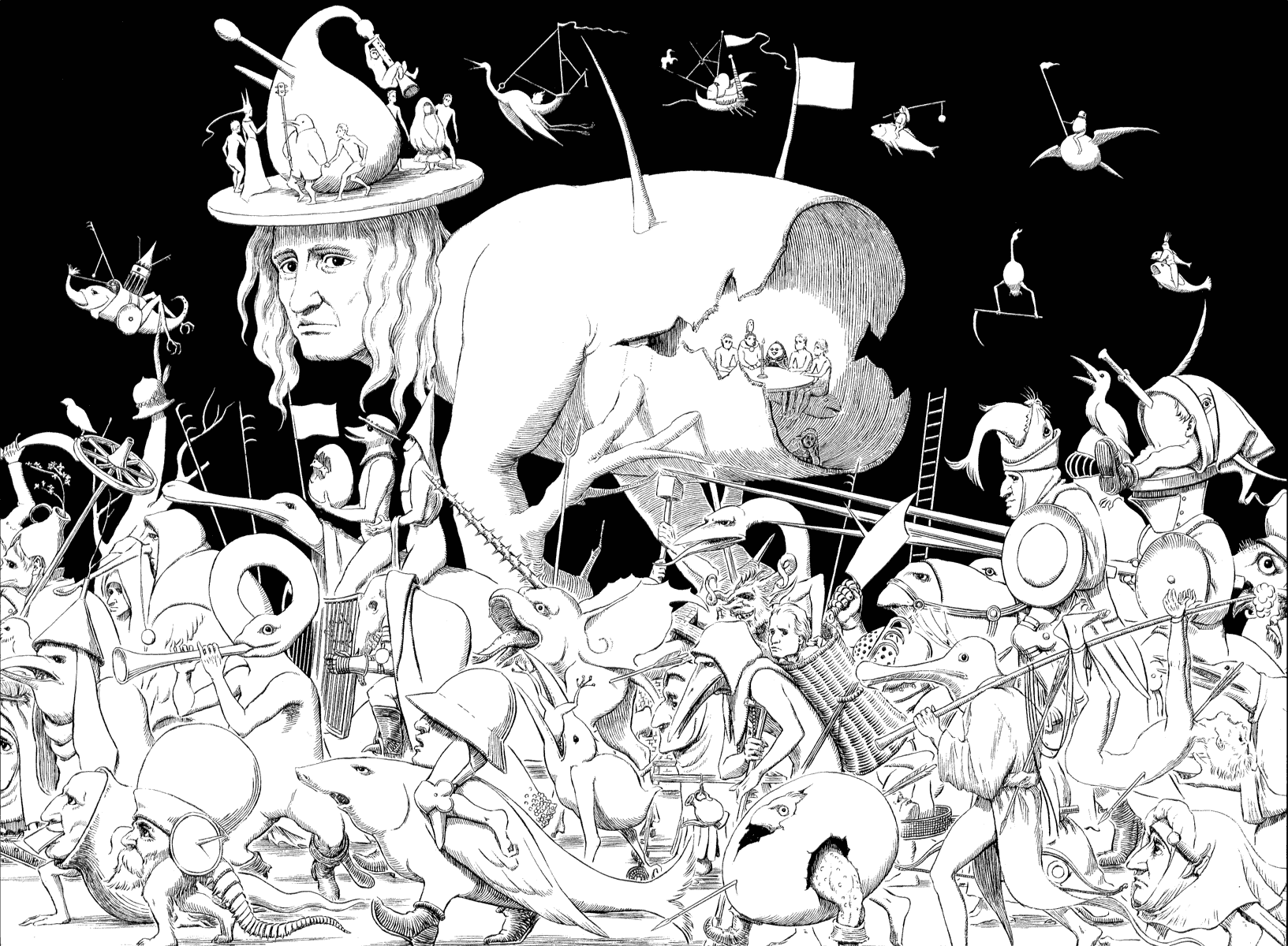

the Souls games have settled themselves into a tradition that will outlive them

As Miura’s work developed, he also began to go directly to Doré and other, even older Western influences. The Berserk panel below is a reinterpretation of the third panel of the triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights by 16th century Dutch painter Hieronymus Bosch. For those unfamiliar with this master of the weird, Bosch’s unique hellscapes capture the surreal and playful side of the dark mythology of medieval christianity. His cast of demons, not dissimilar to the yōkai of Japanese folklore, are part carnivalesque celebration and part terrifying vision of eternal damnation. Miura’s desire to engage with such a reference shows the complex world that hides in plain sight within the bloody pulp of Berserk. Guts is a centerpoint in this rich network of references, tormented by demons in a facsimile of Michelangelo’s Saint Anthony in one panel, then posing like Rutger Hauer in Salute of the Jugger (1989) in another.

Kentaro Miura, Panel from Berserk Manga, 1989-1992

For the Dark Souls series, Berserk isn’t just an influence, it is a mirror image. The world of the Souls games may not have the same pulpy feel as Miura’s work, but it possesses the same appetite for rich historical influences recombined into new and powerful images. The visual sophistication of the Souls games doesn’t only come from the talent of its artists or the clarity of their vision, it comes from a willingness to seek inspiration from every source—not just games and pop culture with their readily accessible fantasy tropes. It’s hard to think of another game series that so readily quotes the masters of its art; confidently repurposing the weighty aesthetics and themes of gothic romanticism and yet still maintaining a taste for the weird and the comedic, for parody and perversity. The resulting tapestry only gains from the mixing of Doré’s damned and Kuniyoshi’s demons, Friedrich’s trees and Miura’s swords. And through this process, the Souls games have settled themselves into a tradition that will outlive them.

Kuniyoshi and Doré may have been working in the dying days of their respective forms, but they were also laying the groundwork for what would come next. Ukiyo-e lived on in the birth of manga; illustration in the invention of the graphic novel. The separation of these two masters, at opposite ends of the Earth, has been slowly eroded over decades of fantastic art and fantastic artists, those who saw only connections, and sought to pursue them to their end. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to think of the world of Dark Souls as a realization of the promise of those two distant greats, and many others between. The hellish congregation of Louis Boulanger’s satanic mass, Kawanabe Kyōsai’s demonic visions of bloody slaughter, the dungeon-like imaginary prisons of Giovanni Piranesi, even the apocalyptic landscapes of John Martin. Traces of all can be found in the DNA of Dark Souls. Not as a single strand, stretching back into the past, but as a vast network, a root system of imagination and inspiration and a desire to pursue the macabre wherever it leads. As Dark Souls 3 suggests, one day this will all be history, stone carvings of another age, and when that happens it will be Souls games that will be seen to have carried the torch, lighting a new path deep into the enticing dark that surrounds us.