Another Legend of Zelda

When Shigeru Miyamoto debuted the latest installment in Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda series at E3 2010, he also made an explicit connection between videogames and fine art. The graphics of The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword, as it turns out, are inspired by the French painter Paul Cézanne and Impressionist art. The artistic influence was unmistakable in the game’s first leaked screenshots, where warm light filters through hazy trees that become masses of solid color in the distance. Yet some fans decried the new style for not being “realistic” enough, following on the heels of the gritty Twilight Princess of 2006.

Is realism defined by how closely the videogame image on the screen resembles our three-dimensional view of reality? Or can games be “realistic” without a glut of polygons?

Miyamoto’s famous dictum for The Legend of Zelda (1986) was that it should become “a garden in a drawer,” a miniature universe to explore like the Kyoto hills that the designer wandered through as a child. It was the first game whose virtual spaces felt large. The individual television-sized areas make up the world as a grid—a walkable continent that rambles through pixilated rivers, forests, and mountains. The top-down perspective, though lacking the intimacy of a behind-the-back character view, uses visual cues like tilted doorways and dungeon walls to suggest a three-dimensional space beyond two-dimensional pixels. In A Link to the Past (1991), the perspective shifts and becomes angled; players are made aware of shadows under houses, tables, and trees.

Early artistic representations of geographic space share The Legend of Zelda‘s technique of using a single flat image to represent a journey through a world. Think of Hyrule seen from above, and then check out the Cotton Map, an Anglo-Saxon manuscript from c. 1040 that represents the entire world as a visual echo of the English island (seen at bottom-left). England, a known quantity, becomes the basis for a spatial representation of the globe, just as Link’s single screen is a microcosm of the world around our avatar.

Hyrule changed forever with the advent of the Nintendo 64. Following in the footsteps of Super Mario 64 (1996), the first fully three-dimensional platforming game that allowed players to act in a facsimile of real space, Ocarina of Time (1998) brought the player down to Link’s point of view. Players are presented with an utterly familiar depiction of three-dimensional space: a world with logical foreshortening and atmospheric perspective instead of the iconographic clarity of the top-down view. But the perspectives of the earlier and later Zelda games are equally limited representations of space. In the former, our vision is cut off by the screen; in the latter, by the direction our avatar is facing and the perceived limits of sight. Ocarina didn’t add anything in terms of spatial realism, but it helped give rise to a new set of graphic expectations for videogames.

Polygons replaced pixels as the de facto medium of videogame design, and players began to demand the three-dimensional modeling, surface textures, and perspective that became the new signifiers of realism. Nothing could be “real” save a rounded, textured Mario or Link. No matter that Zelda is a fairy tale; its fiction must mimic visual reality.

In practice, the games themselves didn’t become much more realistic. Even the earliest Zelda game allowed players free reign in an essentially three-dimensional space, one represented iconographically rather than literally. In Majora’s Mask (2000), Wind Waker (2003), and Twilight Princess, players are limited to the ground-level view of their avatar that Ocarina pioneered, but are free to wander throughout a world that exists beyond the player’s immediate view. They are able to sail a vast ocean in Wind Waker, just as they wandered the interminable forest of that first game in 1986.

It is not photorealism that makes videogames feel real. It is the agency given to the player. In embracing a sense of freedom, Zelda pushes the boundaries of two-dimensional space into three dimensions—just as the best art blows past the boundaries of its medium, unfolding a world of unlimited possibility before the viewer.

Visual Games is a monthly column covering the intersection of videogames and visual art.

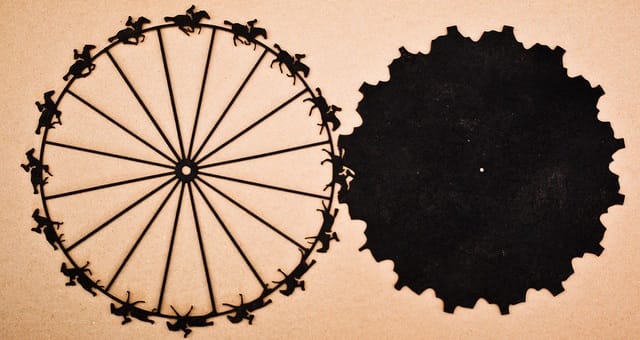

Illustration by Daniel Purvis