Photorealism in Crisis

In certain corners of the world of Super Mario 64, there are graphical glitches that turn a seemingly solid space into a splintered chaos of polygons. Solid walls turn inside-out as the game’s camera freaks out. The same fractures exist in the visual façade of games like GoldenEye 007 and the Call of Duty series—tiled textures extend to cover objects that they don’t belong to; walls or trees that seem to exist in space are actually two-dimensional stage props up close.

What we perceive as a logical world in a videogame is, of course, an elaborate construction, but it’s usually good enough to trick us into believing it. The varying degree of this believability seems to correlate to a videogame’s “realism” quotient; the more a videogame looks like a photograph, the more real we think it is.

There will come a point when photorealism in videogames reaches its zenith—when the grass your avatar treads on looks and bends like real grass, when polygon glitches no longer exist. See a trailer of Battlefield 3 gameplay or Crysis 2 for examples of how the immediate future of videogames reaches toward a perfect photorealism. But what happens after that point is achieved? The photorealistic approach seems to me to be a dead-end street, an aspiration that, once perfectly achieved, leads to a death of possibility.

But what if we shook up this definition of realism and believability a little bit? After all, a videogame is never going to be real. Even a photograph—a chip or piece of film exposed to light—is more inherently connected to physical reality. Videogames, in contrast, are only depictions and representations of reality, artificial approximations. What if, rather than continuing to move toward slicker and slicker approximations of reality, games instead provoked players into new ways of seeing reality, and new ideas of “realism”?

Chasing photorealism has led to some incredible gaming experiences, but it’s also limiting, defining graphical success only in terms of how real something looks. Visual art hit this conflict when photography was invented—if photography was able to instantly capture reality as it existed, long the territory of painting, what was the role of painting? But what rose out of negotiating that artistic tangle were new forms of art.

What if, rather than continuing to move toward slicker and slicker approximations of reality, games instead provoked players into new ways of seeing reality, and new ideas of “realism”?

Photorealism was both an artistic strategy and a movement in the ’60s and ’70s, but photorealist artists didn’t just make their paintings look like photos. Photorealist painters like Chuck Close, Audrey Flack, and Richard Estes used the visual qualities of photography to critique the photograph, destabilizing images that were supposed to depict reality.

Close’s early work, including the staggeringly exact Fanny/Fingerpainting (1985), may seem exactly photorealistic, but on closer inspection the paintings are made up of artificial base elements—Fanny was made by the artist pressing his thumbprint into the canvas over and over. Estes’ iconic Paris Street Scene (1972) reproduces a staid street scene in every detail, but the street on the left of the painting is reflected exactly in the storefront windows on the right side. The painting no longer represents reality as it is, but mingles reality with its own false image.

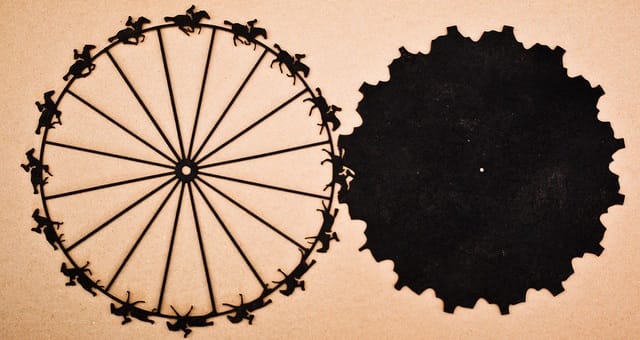

These works make viewers rethink what they’re seeing, and notice what makes painting different from photography. Videogames are fully capable of challenging their players in the same way—think of games that explore or subvert the idea of standard space and representation, like the 2D/3D-flipping Super Paper Mario; the recent Lost in Shadow, which switches foreground for background; or the cel-shaded styles of Wind Waker and Jet Grind Radio. These games abstract from realism, subverting players’ expectations rather than bowing to them. Bernie Schulenburg’s upcoming Where Is My Heart? might even be a videogame answer to cubism, with multiple viewing windows that can be shifted through at will.

Think of the possibilities of further decoupling videogames from photorealism. What might an abstract-expressionist videogame look like? If mainstream videogame designers continue to overemphasize photorealism as the ultimate goal of game development, we may never find out. Though the latest high-texture, high-polygon-count shooter might be flashy and impressive, it’s never going to provoke the player into thinking about the visual world in a different way. That surprise should be the goal of videogames, not the artifice of photorealism.

Visual Games is a monthly column covering the intersection of videogames and visual art.

Paris Street Scene edited by Daniel Purvis