Void and Meddler is lovely but lonely

It’s a gorgeous evening in Void & Meddler’s synth-wave nightscape. The downtempo music is pulsing, rain is falling, and I’m guiding my protagonist Fyn through a market of vibrant neofuturistic goods. I click on some fish, stacked near a bobbing robot merchant.

“No, just no,” Fyn tells me.

I click on the pile of fish again.

“No way.”

///

Booting up the game, I knew from a single glance that Fyn and I were not going to get along. With her hips perpetually half-crooked and a look of withering disinterest carved into her expression, Void & Meddler’s protagonist is all attitude. The plot seems moderately invested in proving that she has some substance, but by the end of Episode 1, I never saw it. Fyn isn’t simply an awful person: she is an unsympathetic and empty void, lacking in personality. Which is a damn shame for a game overflowing with atmosphere and ideas.

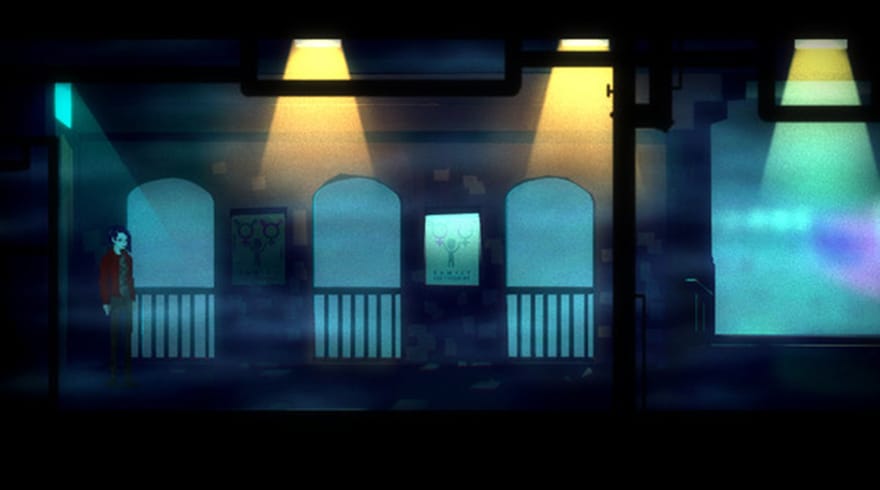

Like Mi-Clos Studios’ bitter space survivalism in Out There, Void & Meddler is evocative and colorful: every screen is awash in gorgeous shades that just “pop” and pretty shit to click on. There’s a pervasive feeling of alienation and loneliness here, a consistency of tone that arises from the moody color palette and music.

Starting out in Fyn’s apartment, I investigate the heap of pills on the bathroom floor, the breathing shape of some one-night-stand still in bed, then settle on a mass of tangled wires and a guitar in the corner of the room.

“I don’t have time for that,” she says.

As we leave her apartment, Fyn calls her bandmates assholes. Shoplifting from the convenience store is her “job perk.” When she opens up to her boss, he shoots himself in the head, then comes back to life. We chase down the one old man in the city who doesn’t have any implants so we can hold him up at knifepoint and pump him for information.

///

In a violet-magenta warehouse full of dancing young people—transhumans, shelled-out druggies, hormone junkies—I hover my mouse over the crowd and ask Fyn to describe someone.

There’s a pervasive feeling of alienation and loneliness

“I’m not going to describe everyone in this room,” she says.

And why should she? The world in which she lives is a neon bloodbuzz. It’s more interesting to look at how the light plays off the smoke and darkness than it is to describe the characters grinding on the dance floor. Like Blade Runner, the cyberpunk society of which Fyn is a product is all glitz and glam: I am seduced by bright lights, moody atmosphere, pulsing drama of synthetic beats. Talking to its inhabitants—or listening to Fyn grouse about the work she has to do to examine her environment—seems mind-numbingly boring in comparison.

I direct Fyn to pick up a magazine on the floor of the subway station.

“Nah I’m not a sports person,” she says dismissively.

///

In one sense, the writing in Void & Meddler is pitch-perfect. One out of ten interactions will read with the crisp distance of strangers passing in a nightclub, which in turn feeds the game’s glorious aura of alienation. The rest of the humor is dark but vacuous: in the chapter’s most memorable and fucked-up moment, Fyn corners an angsty teenager hooked up to a VR game called “Spit on Me” in a vintage arcade. She learns from a gaggle of nearby teens that his girlfriend recently dumped him and he’s having a hard time getting over her.

We need a distraction to keep going in the game, so Fyn eggs the boy on, tells him he’s ugly and doesn’t take care of himself. She tells him that’s why his girlfriend left him, and he’ll die alone, and that she’ll be comforting his girlfriend tonight. Sparks issue from the boy’s VR helmet, and he goes limp in his rig.

“You killed him,” one of his friends exclaims. But Fyn isn’t listening; the floor attendant is already busy cleaning up, and there’s more to do.

///

Void & Meddler is a headgame, like a lot of good cyberpunk. What is actually happening to Fyn? What is real and what is not real? Is her experience one long narrative of a night of suicidal ideation? So little is revealed in this first chapter that it’s difficult to say. And in its stubborn refusal to adhere to convention or basic narrative, Void & Meddler lags significantly. Throughout the episode, a number of key moments play out—promises made, favors cashed, teenagers fried—that might lead to some legitimate payoff in later episodes, but who can say at this point?

Void & Meddler is a headgame, like a lot of good cyberpunk.

And it’s here that Void & Meddler falls short: not for lack of promises, intrigue or atmosphere, but because its plotting is directionless, its protagonist entirely unlikeable. The game is aesthetically rich, but it lacks heart. Fyn is the epitome of a self-entitled city brat: catty, selfish, and unduly world-weary. And while chapters 2 and 3 might reveal more, it’s hard to muster any compassion for a story about a character as unrelateable as Fyn.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.