VR, the new arcade, and the presence-crisis of videogames

The first thing I did at PAX East 2014 was play Oculus Rift. The official Oculus booth had lines two hours long, I’d heard. At a small kiosk along the periphery of the expo floor, Hyperkin, the only official peripheral maker signed on with Oculus so far, was showing a demo of a gun-controller used while wearing the VR goggles. Three curious onlookers waited to try. I stood nearby and soon strapped on the prototype whose technology and name had been bought a week earlier by Facebook for $2 billion. I wasn’t sold on VR, and I’m still not. But if promises are kept and potential fulfilled, that price may make the Louisiana Purchase look like a rip-off.

Inside this virtual world I walked around an empty industrial yard. I looked up and, sure enough, saw clouds. Even within the chaos of a convention hall filled with thousands of people, this simple headset provided a surprisingly real respite from the masses. Soon I jumped for the roof of a stationary train and missed. Like with any sea change, we will need to relearn certain rules. I was running a race after having crawled for the first time. The goggles were the original prototype, too, a revolutionary step already outdated. Soon I felt dizzy. I turned around and thought for a moment I was going to fall down, not into a bottomless pit in the game world but right there on the expo floor. I grabbed the goggles off my face and breathed in a bit deeper than usual.

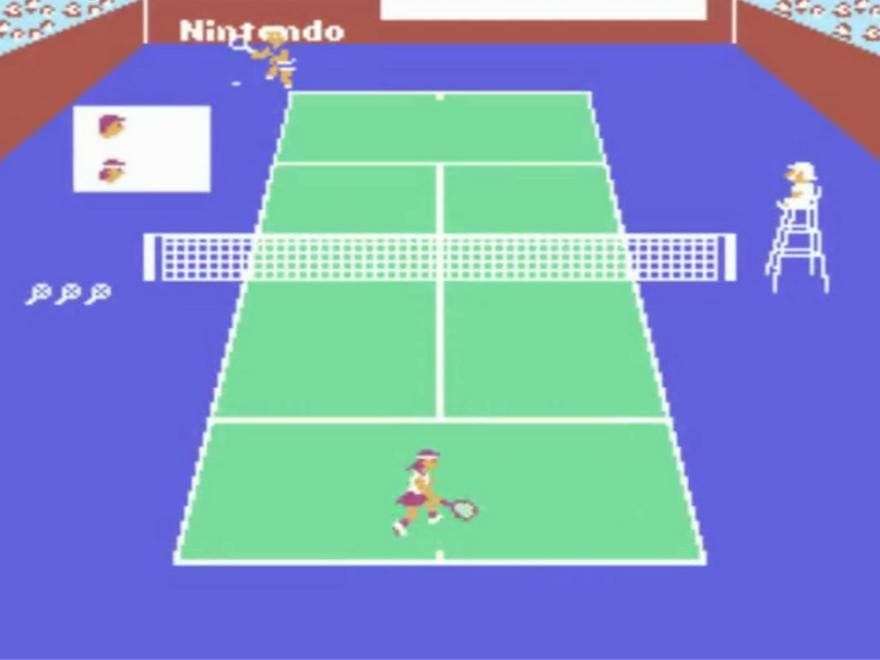

The second thing I did at PAX East was play Vs. Tennis against a stranger. Reps from Funspot, the largest arcade in the world, located in Weir Beach, New Hampshire and home to the American Classic Arcade Museum, turned a room in the Boston Conference and Convention Center into their best approximation of an arcade circa 1986. Rod Stewart played on the radio. Projectors shot fireworks of colored light from floor to ceiling. Upright cabinets, classics like Asteroids and Punch-Out!! and Dragon Lair, lined the walls. A ponytailed gentleman sat down at the Vs. Tennis machine, a dual-display machine based on the NES launch sports title. Before this match could happen, Gary Vincent and his staff at the ACAM had to lug 14,000 pounds of history in across two states.

“We have to load the trucks,” Vincent wrote me in an email, “then unload them at PAX. Then we have to get the games arranged in the room. [W]hen the show is over, we have to put them all back up on flat rolling dollies, load them into the trucks and drive two hours back to the museum… It is a lot of work.” All for three days of chance encounters like mine with Mr. Ponytail.

Vs. Tennis had a queue in 2014.

I sat in the empty seat opposite him and soon we took to the court. Five minutes later, I was up 5-0. He was serving to stay in the match. I saw the top of his head directly across from me. Feeling a twinge of pressure, I missed his first serve. 15-love. My next return sailed just wide. I scraped together a few points to tie it 30-all. A couple other attendees stood next to the machine. “Has anyone called next?” they asked. No one had. Vs. Tennis had a queue in 2014. My opponent took advantage of the distraction, winning the next two points and the game. He raised his arm in mock-triumph. “Yes!” he yelled, and that I saw his outstretched arm and heard his voice is important, because it spurred me on to dig down and focus. I served an ace and took the next three points easily, winning the one-set match, 6-1.

“Good game, man,” I said, and though we didn’t shake hands, we might have if we weren’t in the middle of a conference center filled with 60,000 germ-laden bodies. We relinquished our seats to the next combatants and went our separate ways.

///

There’s a lot of chatter about “presence” in the games industry recently. That’s the key term when used to differentiate the Oculus, and Sony’s own VR solution, Project Morpheus, from playing traditional games. You feel as if objects aren’t burned onto a flat screen in front of you, representatives say, but there, in the room with you. Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg feels Oculus could revolutionize social media. One advantage he cites: the possibility for eye contact.

Games have never been so immaterial.

Videogames are having a presence-crisis. Games have never been so immaterial. As digital downloads carve out a larger portion of overall sales with each year, we lose something tangible: this experience boiled down into molded plastic surrounding circuitry. The advent of Steam sales and Humble Bundles provide frugal ways to amass hundreds of games; ostensibly a good value, but at a questionable loss to the attention afforded each purchased title. In forty years the games industry has expanded and contracted at once. From the arcade to home consoles to storage memory: What was once a public place stocked with hulking giants is now condensed onto a single silicon chip. What is the unintended result of this consolidation? An attempt, from all corners, to recreate the concept of presence. To pretend we’re standing again in the same room.

These fractures are visible throughout PAX East. Out on the expo floor, hundreds of developers show their wares to hungry players. But there are no discs or cartridges stuck into consoles. Just a file on a hard-drive. Swing over to the Classic Console room and stand gaping at things: the Atari Jaguar’s surprisingly comfortable 18-button controller; an Apple IIe with a floppy disc of Ghostbusters by Activision inserted, ready to play; an original Home PONG system. Two kids, younger than the game, twist the control knobs and yell at each other. Their actions, out of context, might have been adjusting volume on a car stereo. But something else is happening. They can feel it.

Others can, too. Behemoth, makers of Alien Hominid, Castle Crashers, and BattleBlock Theater, install their games each year at PAX into homemade arcade cabinets so players can stand next to each other, clack the joysticks back and forth and pound on plastic buttons with their hand. Elsewhere, off the main lobby, a lone cabinet for Samurai Gunn stands in a hallway; throughout the weekend I never see it unplayed.

Even at Sony’s booth I saw these grasps at an anchored, tangible physicality. Their VR helmet was not shown to the public. Instead they touted another kind of presence. Towerfall: Ascension played on a massive television in front of a couch and two ottomans. Matt Thorson’s archery-arena battler was an OUYA exclusive before releasing early this year on Steam and PlayStation 4. Much has been written about the ridiculous fun of slinging arrows across a pixellated dungeon, to which I can only add more of the same. Thorson’s choice to nix online play, in what many called the best multiplayer game of last year, has drawn criticism by those used to long-distance slaughtering. But he’s stuck to his arrows. He realizes, in 2014, proximity is a rare but essential commodity.

Multiplayer that’s restricted to the same room “can allow players to express themselves socially through play, and get to know each other by interacting in the game,” Thorson told Ryan Clements this past March. “And those interactions can bleed into the real world. It’s really simple, but so powerful.”

When Towerfall’s green archer, played by the stranger on the right side of the couch, fell from above and launched the finishing blow to my helpless red archer, I looked over and caught his eye. He shook his head, looking away, sheepish in victory. But for a moment we saw each other.

Twitch.TV, the streaming website with over forty-five million visitors a month, had a huge presence at the event, with devoted panels and a large centralized booth on the floor. Instant streaming of gameplay is one of the standout features of both Sony’s and Microsoft’s new consoles. When watching others play online, we can see their faces. But they don’t see us. Nor are they looking.

///

The kind of presence evoked by Oculus Rift or Project Morpheus seems, for now, illusory. Communication is all one-way: we imagine ourselves to be in a space, but the space doesn’t yet imagine us back. Virtual reality hooks into some pre-lingual nerve endings; we don’t have the vocabulary yet to describe what it feels like, yet we can feel it all the same. But this intuition has always been with us. It’s where videogames first sprang from. A Japanese teen knows to reflect the ball back in PONG, just as an American child knows to shoot the incoming Invaders descending from Space.

Electronic games began as analog objects.

During a panel discussion on the transition from early 80s arcade culture to our present era of home consoles, Jonathan Hurd, creator of Food Fight, showed off design documents from the development process: plans sketched out on notebook paper; pixel graphics colored in on graph paper; printed faxes from Atari, discussing the cabinet art. Electronic games began as analog objects. And the inverse, of course, exists: these digital places manifest themselves in our physical world, be it through cosplay, card games, t-shirts, foam props, or cardboard Creepers.

Before leaving I swung by the booth for Playism, a group devoted to bringing Japanese indie games to the west, and vice versa. I wanted to play Kero Blaster, the next game by Daisuke Amaya, AKA Pixel. He’s best known for Cave Story, a game he distributed freely online back in 2004 before a swell of positive opinion lead to an enhanced re-release onto WiiWare, Steam and 3DS. Kero Blaster is similar on the surface: A 2D platformer where you run, jump and shoot through pixelated environments, learning more about your enigmatic character, a bright green frog who stands on two legs. Another attendee was playing the PC game. I saw that the game was slated for iOS as well; I asked a booth attendant if I could play that version.

“Oh yeah, I think Amaya-san has it on his phone.” With that he called in Japanese over to a short man standing behind the table. The man was dressed in a head-to-toe frog suit. He grabbed an iPhone from the table and joined us. This was Pixel himself. He cycled through his many apps, bringing up Kero Blaster, and handed it to me. On the back of the phone were three stickers placed haphazardly, a trio of cartoon bear heads, each a bit more faded than the next.

I played the man’s game on the man’s phone while he watched. After a level I handed the phone back to him and said how I loved his games; he looked to his translator, who explained, and Pixel said, “Thank you,” with a slight bow. The game itself was pretty fun. But what I felt more than the enjoyment of blasting forest critters and being propelled through the air via jet-pack was something else entirely, something we lost a long time ago, something we’re trying so hard to get back.

Header via Sergey Galyonkin