This War of Mine is not fun, but you should still play it

On my first playthrough of This War of Mine, one of the game’s three survivors died of her poorly treated wounds and another was beaten to death while scavenging for supplies. The last of the group killed himself, having lost hope for a better future. That there was a sense of relief when the screen faded to black and stated “You didn’t make it” in plain bolded text speaks to the kind of despair that characterizes the game. Trying again, loading up a fresh attempt at helping a group of civilians survive amidst the wreckage of their ruined city, the menu’s illustrated background displays a wall where someone has spraypainted “Fuck the war!” across the bricks. As the player watches yet another new batch of characters ground into misery within the warzone that graffiti starts to feel like it probably contains one word too many.

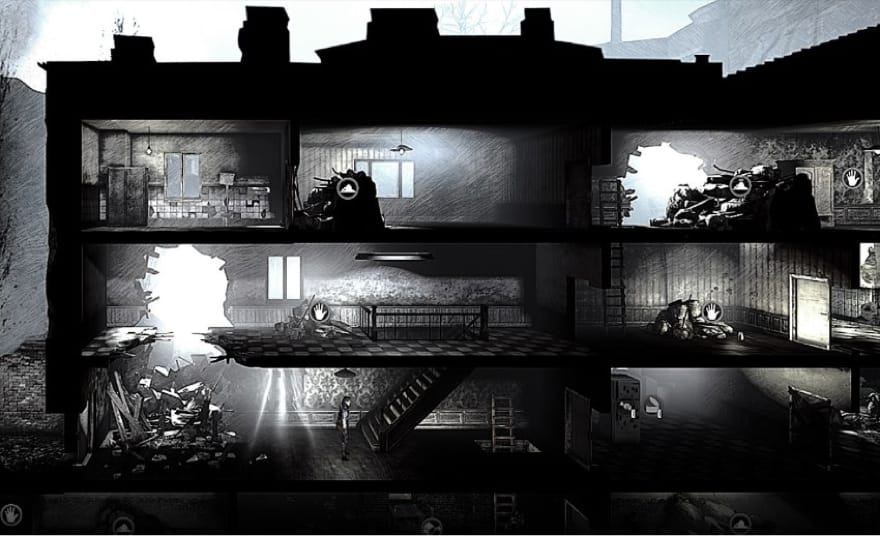

11 bit Studios’ act of subversion is to release a videogame that makes war not thrilling, but a miserable slog. This War of Mine is a slow-burning, gray-skied journey through the special sort of depravity only humans in the direst need are capable of reaching. Without worrying about the exact nature of the conflict or spending more than a few sentences on how a group of civilians have ended up sheltering together in the same dilapidated house, the game offers control of a handful of people and asks players to help them figure out how to stay alive in the apocalyptic landscape of an active warzone.

This, it turns out, is not glamorous, mostly taking the form of carefully managing essential resources (food, medicine) and important supplies (building materials, tools). In order to keep the survivors from starving, getting sick, or becoming too sad to complete basic tasks, the player must use workbenches to craft simple luxuries like comfortable beds, cooking stoves, radios, and armchairs. The daytime portion of This War is Mine concentrates on making the tough choices of which household items most need building, who gets to eat, and when to let a wounded person rest rather than help get things done. At sunset the stakes rise further. A character can be assigned to sleep overnight, guard the house from thieves, or be sent out to scavenge supplies from homes and buildings in other city districts. Every action is vital, but it’s impossible to perform them all.

The ruthlessness of dictating life on this scale is part of a delicate balancing act. Necessity often forces players into the kind of amoral decision-making required while navigating Lucas Pope’s brilliant faux-Soviet border guard simulator, Papers, Please. This War of Mine, too, erodes any long-term ability to maintain “good” characters by forcing players to put themselves in the mindset of desperate people who have little choice but to act poorly to continue surviving. Is it better to guard a dwindling set of resources by staying at home during the night, or to head out to steal life-saving materials from the people in nearby buildings? In one instance, having already seen a member of the group killed and running dangerously low on medical supplies, a character scavenges everything she can from an elderly couple’s house. While rooting through medicine cabinets and emptying a refrigerator, the victim trails behind the player character, pleading for her to leave enough behind for them to live on. Ignored, he runs upstairs and hides with his wife in fear. In another moment it may be necessary to give priority access to food, medicine, and bed rest to the member of the group most adept at stealing during the night-time sequences. His ability to bring home fresh supplies has to be protected, even if the survivor who is nothing more than a talented cook starves to death or succumbs to illness as a consequence.

This is heartbreaking. Success in This War of Mine often comes down to being willing to make the kind of decisions that we’d really rather not want to imagine ourselves even considering. Throughout all of this the war comes across as an unstoppable force of nature, always present in the background of the game. Its effects are felt in the districts too dangerous to travel through, the distant thunder of shelling, and the crack of a sniper’s rifle shot. The constant, low-boiling menace of conflict lends gravity to the situation, while being forced to control the few, potentially life-saving choices left to This War of Mine’s characters encourages a level of empathy uncommon to war games. The act of slowly becoming monstrous—of turning into the kind of person who can rationalize stealing medicine from an old man or enabling the slow starvation of a weak friend—brings home the realities of existence as a wartime civilian.

It’s only in 11 bit Studios’ efforts to introduce structured narrative elements into the game that This War of Mine stumbles. While the short biography paragraphs accompanying each survivor’s portrait provide a welcome backdrop to their character, written updates detailing their mood changes or reactions to major events (like a housemate’s death or the murder of an enemy while scavenging supplies) are too constraining. The awkwardly phrased dialogue doesn’t help either. Rather than read a character describe his difficulty coping with the stresses of wartime through a diary entry stating “It’s difficult here, but you know how we did it on our street?” it would have been far more preferable to have nothing—to allow each survivor’s personalities to exist naturally within the player’s head.

When this aspect of the game is ignored, though, This War of Mine manages to convey an important message very well. By turning the player into an active participant in the cutthroat rationale of life as an ordinary person attempting to survive a warzone, it encourages a level of empathy only possible through interaction. Instead of simply hearing the stories of people who suffer unimaginable hardship as civilians during war, the audience is asked to inhabit these narratives. When our choices became their choices—as completely awful as they may be—we can better understand the ground-level tragedies taking place across the globe at this moment. 11 bit Studios’ greatest success with This War of Mine, it turns out, is in creating a videogame that is profoundly unpleasant to experience.