The War Must Go On

In an early level of Modern Warfare 3, Nikolai shouts, “Do whatever this man tells you!” at the player, who is in control of newcomer Yuri. He is being indicative of the style of game Infinity Ward has perfected: linear, prescriptive, and closely authored. The story told by its Modern Warfare series—itself a sub-series of the military shooter behemoth, Call of Duty—is not a great one, but it is a story superbly told. This is because it understands how a multitude of playable characters can flesh out a world that, by all accounts, should be forgettable.

Its tale of disenfranchised, ultranationalist Russians seeking revenge on the entire Western world for Old Russia’s demise in the form of a nuclear holocaust may as well have been conjured by Tom Clancy at his most deranged and directed by Michael Bay at his most bombastic. The Modern Warfare series wants you to believe it has a nuanced understanding of global geopolitics, but during Modern Warfare 2 in particular the written plot so often spirals into incredulity and incoherency that you need a sit-down with Wikipedia to make any sense of it.

Yet the previous Call of Duty games, set during various battles of World War II, demonstrated a complex and vast network of relationships and conflicts between nations across the globe. U.S., British, and Soviet playable characters were used to show that the war wasn’t won by an elite group of superhuman heroes on a single battlefield, but by a multitude of typical, everyday people from all over the world fighting on a range of continents. People who have names if you put your crosshair over them.

Set during a fictional near-future conflict, Modern Warfare is undoubtedly about superhuman heroes and villains—Soap McTavish, Captain Price, and Makarov are not your everyday men doing everyday things. But neither can any one of them see the whole picture. They are still apparently working within and dependent on a vast support network of orbiting gunships and squads gathering intel on the other side of the world.

Each entry in the Call of Duty series, even more than the previous, shows a superb understanding of exactly what videogames are capable of that film isn’t. Namely, the ability to have the player participate in the action, not as themselves but through an “other.” Or, in the case of Modern Warfare, through as many others as the game needs to communicate the whole story. It’s through these others that Modern Warfare grabs hold of players, who momentarily suspend their disbelief of its fundamentally problematic take on “modern” conflict and become utterly committed to the story, absurdities and all.

In a videogame, you must do what the character must do in order for the show to go on.

The Modern Warfare games are not afraid to yank you from one body and put you in another role every other mission. Instead of displaying a cut scene or a quick line of exposition that tells you that the Russian president has been kidnapped on his way to peace talks during Modern Warfare 3, you participate in the kidnapping through a Russian secret serviceman who is frantically trying to defend the President and his daughter. Instead of just hearing about that time Captain Price many years ago infiltrated the ghost town of Chernobyl to assassinate a warlord and prevent a nuclear attack, you are able to participate in the infiltration yourself through the eyes of a young Price.

You live every moment of the story and, in the process, will often find yourself alongside a character you were “inside” just one level ago. In Modern Warfare 3, you watch as one playable character from the first Modern Warfare dies; you watch another one kill; and in a mind- and time-twisting thirst for redemption, you revisit a scene from Modern Warfare 2 to attempt to kill a playable character you previously played in that time and space.

In a videogame, you must do what the character must do in order for the show to go on. In Modern Warfare‘s over-the-top set pieces, it is the playable character that tells us why we are running down this particular corridor shooting these particular enemies. These shifts in perspective and scope, showing multiple sides of the story, allow us to empathize with different sides of the same conflict. You are fighting Russian soldiers on one mission and defending the Russian president on another. You are crossing a country field while an allied gunship tears apart enemy soldiers and farmhouses alike in horrific explosions on one mission; and you are the gunship’s gunner on the next, quietly remarking on a “good kill” against the eerily peaceful, air-conditioned hum of the gunship’s interior, walled off from the conflict on the ground.

When critics decry the minimal player choice in Modern Warfare, saying it may as well be an action film, they are closer to the truth than they realize. Modern Warfare is just like an action film, but it isn’t player choice, or control over a scene, that it takes away—just the power to change that scene. You are in control of your own actions, but you are still following stage directions.

By ensuring that the player understands the character’s role, the Modern Warfare series is able to superbly tell a mediocre story, one whose politics are implausible and action is in no way representative of modern warfare. Unlike other games inspired by film, Modern Warfare relies little on exposition or cut scene because the player is always there-unable to affect the narrative, but always a part of it. It is something more videogames need to understand and take advantage of: that the player’s primary allegiance is to the playable character, and their primary objective is to make sure the show goes on.

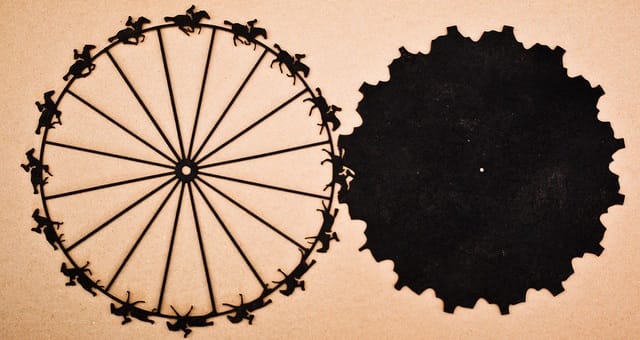

Illustration by Daniel Purvis