[This article contains spoilers for the finale of Life is Strange.]

I am a compulsive spoiler seeker. I tried my best to avoid any information about the finale of Life is Strange on its release day while I was at work, but I couldn’t control myself. I searched “#LiSfinale” on Twitter and almost immediately saw reactions about the ending, some of which were downright outraged at the lack of choice in the ending. I didn’t seek any information beyond that, but I went into the episode ready to be disappointed.

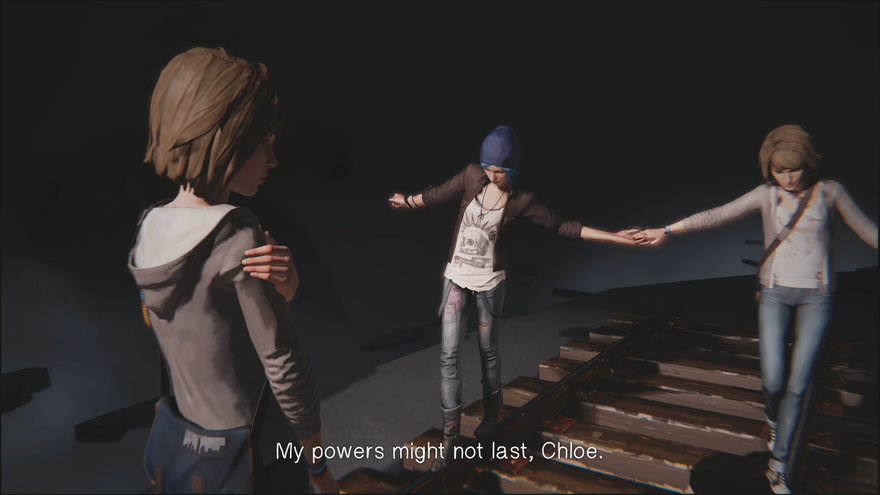

About two hours after I started episode 5, I stood on the hilltop beneath the lighthouse with Chloe, who is protagonist Max’s best friend and maybe girlfriend, and was listening to her ask Max to reverse time to the beginning of the week and let her die. All of the times Max has reversed time already seem to be for naught. There is no visible timeline in which she can both stop the storm and save Chloe.

This futility is a gut punch. Even though the dialogue and pop culture references will age poorly very quickly, I still think Life is Strange will hold up as one of the best time travel games in videogame history alongside The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask.

In Majora’s Mask, Link is forced to repeat the same few days until he can stop the moon from crashing into the earth and somehow find time to solve the relationship and business problems of Clock Town’s residents. As Link, you help reunite young lovers, save cows from kidnapping, restore the purity of polluted landscapes, return stolen eggs to a mourning mother Zora, and more. But it’s impossible to do all of these things in a single set of days. Inevitably, the clock will reset and, though Link retains the knowledge or loot gained from his quests, no timeline exists in which all of the problems are solved.

Futility is a gut punch

The game’s final cutscene sort of ruins this by showing everyone having their happy ending, but generally speaking, there is an implicit tragedy in time travel stories when done correctly. The logic of a multiple timeline theory of time travel dictates that, somewhere in the multiverse, someone is living with each choice you made.

There’s a reality where Link only helps the women on Romani Ranch. Somewhere, he’s a Deku forever. Elsewhere, everyone gets saved. It’s the same in Life is Strange, which is what makes the ending so striking.

Max thinks she can save Arcadia Bay from the tornado because of course she does. She probably grew up on a steady diet of teen hero stories and felt like she had been dropped into one when she discovered her time travel powers. But the reality is a lot more difficult. In reality, a pair of teenagers can’t save the world with their heart and good intentions, even if one of them does have a magic power.

Given that we see Max meet a version of herself in the nightmare sequence, it would seem Max is conscious of the fact that she’s only living with one version of her choices. In some reality, Chloe is still paralyzed and her parents are drowning in debt to the hospital. Somewhere, the girls never reconcile and Mr. Jefferson and Nathan probably got away with murder. But from where Max is standing, she has to stop changing the timeline and she has to live with one final choice.

In the end, I chose to sacrifice Chloe over the town. On the surface, the choice seems to be one of siding with whom the player is more emotionally invested: your best friend or everyone you’ve helped in the town. But after that first gut check, the choice gets much more complicated.

For me, it was a choice motivated by fear and respect for Chloe. Of all the characters in the game, Max has messed with her life most—mostly without her consent—so her plea to just let her life end was compelling. And on a totally selfish end of the spectrum, I was terrified for Max about what kind of person Chloe would become if Max sacrificed the entire town for her. If Max saves Chloe, she’s also essentially killing everyone else Chloe loves and Chloe knows it.

A pair of teenagers can’t save the world with their heart and good intentions

I watched the ending where Max and Chloe drive off into the sunset and I can’t help but imagine that by the time they make it to California, Chloe’s anger would be gnawing at her. I don’t think their relationship could survive that.

Both endings are selfish in their own way, but I chose to give Max the mercy of not seeing her love ruined by resentment. I let Chloe have agency in choosing her death.

Unlike other games (ahem, Mass Effect 3 and, to an extent, The Last of Us) where player choice shapes the plot only to pull the rug out at the end to reveal the pointlessness of your decisions, the limited impact of your choices in Life is Strange serve a narrative purpose.

Life is Strange’s finale shows that the amount of heart you display and the number of good intentions you have can’t make up for your bad choices and delusions of control. You can’t have your cake and eat it.

It would seem that the ending in which Chloe dies is the “canon” ending. The game certainly gives that ending more love and attention. We finally get the long-awaited kiss. We see Max go through grief and helplessness. We see Chloe’s funeral and a final appearance from the blue butterfly.

The final shot is of Max’s face, seemingly gaining some sense of closure, but I think the real tragedy here happens with the player after the console is turned off. What haunted me for days after I finished episode five was that, in the reality where Max saw Chloe die for good, that version of Chloe didn’t know what the girls had gone through. That Chloe never told Max she loved her.

It’s the ultimate denial of closure. Max is the only one bearing the emotional scars of the multiverse. She doesn’t have anyone to share it with.

The choices Max made have all been entirely meaningless because she literally ends up back where she started. This is one of the bravest narrative choices I’ve ever seen in a videogame. It exposes our powerlessness and leaves us to sit with it.