We talk to NHL ’94’s producer to figure out why the game is still revered today

Jeremy Roenick in NHL ’94 was a beast. “A big guy, relatively fast, an accurate shot, great checking ability,” says Michael Brook, the game’s producer. This is true to life. Brook hired a professional scout to rate every individual player for the 1994 season and then fed those ratings into the game. What followed, however, was unexpected. In being digitized, Roenick had emerged as the god of hockey.

It’s generally accepted among the cognoscenti of videogame sports that virtual hockey was perfected with NHL ’94. This is why on its twentieth anniversary Electronic Arts included “94 Mode” as a callback in NHL 14. There are those who claim, boldly, that ’94 was the greatest sports game ever released, placing Roenick among the medium’s elite. The latter, at least, is hard to argue with. In the pantheon of legendary videogame athletes, only Bo Jackson (Tecmo Bowl) and Michael Vick (Madden 2004) hold a candle—untouchables capable of running circles around entire opposing teams.

The thing is, these guys were hardly as amazing in real life as they were in the those games. Don’t get me wrong. The real Roenick was a scoring machine. He was amazing, just not that amazing. In reality, he probably wouldn’t make the cut on your team-of-the-forever, but in digits, he’s your first pick. For whatever reason, the skills that make an athlete truly memorable are different from the skills that make them great athletes in videogames.

Roenick was the perfect specimen of statistical virility. If you saw his stats at a sperm bank, you’d want his stats.

If Roenick wasn’t the best player on ice, who was? Well, Mario Lemieux was the M.V.P. of the previous season, while Roenick throughout his eighteen season career was never once awarded the Hart Memorial trophy. As Brook says, “Lemieux was a stud of the game.” But unfortunately for Lemieux’s videogame representation, he was also injury-prone. (He was stricken with lymphoma during that season and was still scoring champ.) This made his valuation drop in a game that sensationalized teeth-dislodging hits.

Checking, or the art of driving your upper body into another human being while holding a hockey stick, was huge. “You’d lay a guy out and you might knock him out for the rest of the period or the rest of the game,” Brook says. At the CONSOL Energy Center, home of the Penguins, you’re not going to see ten crushing hits within a span of one minute. But on the Genesis, that happened nightly. “It was part of the strategy,” he says.

Roenick was the perfect specimen of statistical virility. If you saw his stats at a sperm bank, you’d want his stats. Namely, he was tougher than most anyone on the other team. “All his size came into play,” says Brook. “He delivered a powerful boom.” That applied not just to busting chops, but also to his knack for crushing one-timers—that is, to receive a pass and without blinking send the hard rubber disk flying towards the goalie at full strength.

On top of that, he had speed. “We had a burst move,” Brook continues, “so, if you had a really fast guy to begin with, he could blow by everyone.” Put those two attributes together in any game and it’s hard to lose. It was everything you needed to make your friend or younger sibling fume.

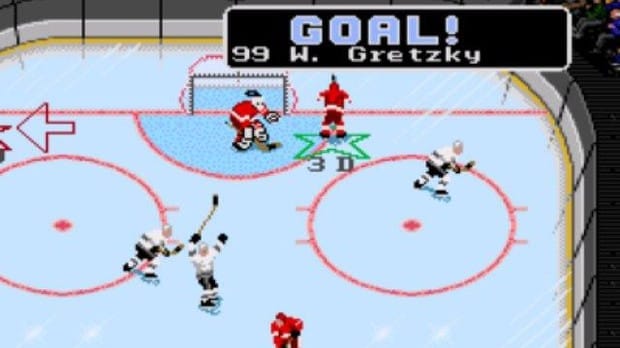

The speedball of bulk and haste is a lethal combination in many games, but especially in NHL ’94. Probably its biggest victim was Wayne Gretzky, who had neither—although he may be the most legendary hooligan on blades. In real life, Gretzky was always lanky and slow, and he became slower as he aged. In ’94, that didn’t change, and it cost his virtual self dearly.

Gretzky has the highest awareness rating in NHL ’94, but it turned out that having good intuition made little difference over the course of three periods.

What made Gretzky Gretzky were the numerous intangibles, things that couldn’t be measured easily, if at all. Whereas a player’s size, speed, and accuracy could be ticked in a box, attributes like intelligence are hard to quantify, and “everyone knows Gretzky had the best awareness of any hockey player ever,” Brook explains.

As it stands, virtual Gretzky has the highest awareness rating in NHL ’94. They programmed it in. But it turned out that having good intuition made little difference over the course of three periods. While it’s true that Gretzky is a formidable adversary when he’s being controlled by the computer, that all changes the moment you take over—which you’d want to do, because who wouldn’t want to play as Wayne Gretzky (aside from Edmonton Oilers fans, maybe).

His phenomenal skill evaporates, as it becomes you the player who’s responsible for knowing where the puck is. “It’s marginalized because your awareness probably isn’t as good as his,” Brook says, which goes a long way towards explaining the “Gretzky is a little bitch” scene in Swingers. It seems the idols of sports possess talents that just don’t translate very well to a gamepad.

Alternately, Jeremy Roenick, great but not the greatest, had a skill set that meshed perfectly with the palms of the player. It was his moment to shine, to be adored and feared and hated and banned by legions of sports game players. To be name-dropped by Vince Vaughn. To be legend.