Weapon Shop de Omasse picks apart videogame conventions

The game begins in medias res, four 8-bit RPG heroes attacking “EVIL LORD” in a turn-based battle. With one final slash the pixellated enemy is defeated. The screen fades to black. Time passes … until the Lord predictably returns once more. A title screen appears. The sequel to the latest generic role-playing game has begun. There’s one disclaimer: “But the heroes will need weapons…” Now we’re taken to another title screen, this one for the game you’re about to play, a game taking place within the confines of another, nonexistent game. Welcome to Weapon Shop de Omasse, where even the title screen is a punchline.

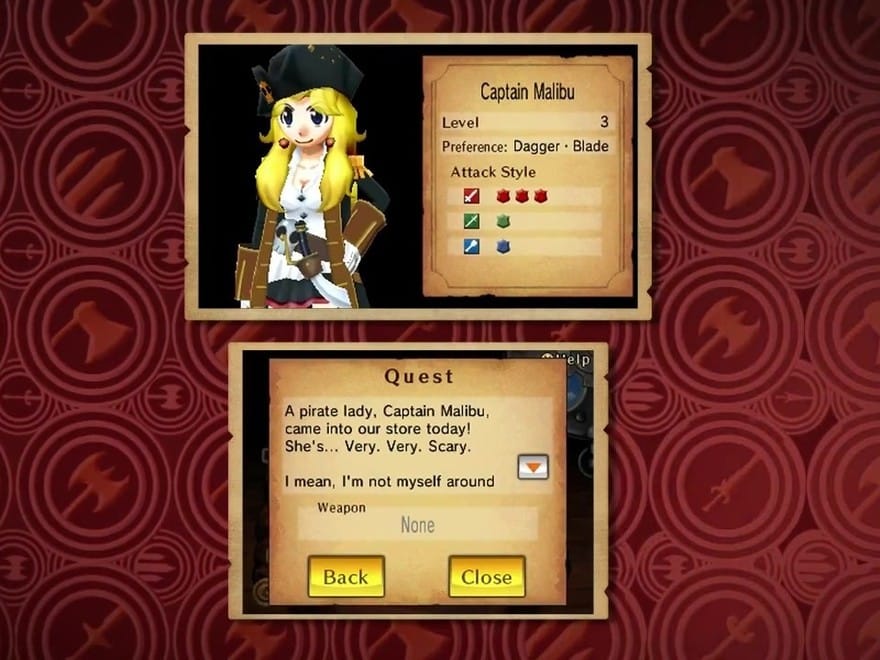

You play as an assistant to a blacksmith, crafting and renting out weapons to a recurring cast of heroes. Once a weapon is requested, you select from Daggers, Swords, Staves, Clubs and Axes (among others). A music track begins. With a molten lump of steel on the bottom screen, you pound in time with the rhythm as a temperature gauge slowly goes down. Between verses, place the lump in coals to keep it hot; when you’re finished, submerge the weapon in water to finish the job. This is the only action you’ll be doing for the entirety of the game.

Here, the role is one of vicarious observer.

The point of Weapon Shop stems from witnessing, not engaging in, adventure. For such a broad title, “role-playing games” always infer the role you’re playing is active and heroic. Here, the role is one of vicarious observer. While crafting weapons, you read a text-scroll (drolly titled the “Grindcast”), updating you on the actions of your clients. The amount of damage dealt is but one kind of information given; precedence is given to a going internal monologue, or even the one-sided repartee of the hero, chatting it up with their dueling monster.

Others observe you, as well. You and your clients are treated like characters in a sitcom. An off-screen live audience reacts to certain lines. They laugh at jokes (with typical laugh track consistency). They audibly inhale at moments of surprise. They applaud the entrance of a new character. When things go horribly awry, a character will saunter off to a chorus of boos. You learn quickly this is not a game about questing toward the ends of the earth to defeat a mighty foe; instead, this is closer to a visual novel, or rather, a gamified soap opera.

In true soap opera fashion, what someone tells to your face is not always the same as what they’re thinking. These plot twists are revealed through actions on the field. But you’re always stuck in your shop, shown on the top-screen, while the action-via-text scrolls on the bottom-screen. So while the boisterous Frenchman swings the Rapier you hammered out of iron ore, you’re shown petting your dog, or dusting the leftover swords.

The ‘Cast is something like a social media feed, complete with anachronistic hashtags. An NPC (named NPC; his quest is for a real name) notes the shine and heft of his rented dagger, followed by “#weaponreviews.” Other quips skew more clever. It’s worth keeping a notebook handy, if only to copy down the inspired insults flung at monsters during battle. “Thou pigeon-brained, puss-grown, carrion cankersore!” has a certain poetry to it. Better still is the punchy brevity of “craven milksop.” But most commentary is not trying for period accuracy, nor even a contemporary elegance. At one point, a surprise attack yields an exclamatory “Zoinks!,” which sounds kind of odd coming from an austere samurai.

“Kind of Odd” is a good descriptor for Weapon Shop. This oddness is welcome after the spit-shined perfection of so many modern games that are playtested and focus-grouped into a homogenous sort of “playability.” It’s no surprise the writing and design comes largely from a single Japanese comedian, Yoshiyuki Hirai; tasteful or not, Weapon Shop bears the mark of a singular vision, even if that vision goes a little cross-eyed at times.

There’s a strange undercurrent of forbidden sexuality throughout, another surprise given the light-hearted tone. One hero, Mr. Grape Kiss, is a giant who shakes the shop’s foundations every time he enters. He also wears a purple wig and lipstick while chest-hair sprouts from his open bustier. While in battle, he repeats the slur of an enemy—”You called me an ugly gay guy?!”—before smiting him with his rented mace. Later, back at the shop, he’ll lean down close to your face and warn you of future intentions: “Maybe in five years you’ll be a big strong MAN, and then I can really let you have it…” Upon telling your boss, he admits that, in addition to weapons, perhaps the shop should start renting out you. This game earns its Teen rating; the ESRB description includes “suggestive themes,” though I did not anticipate underage prostitution.

But for all its laughtrack-infused zaniness and questionable forays into taboo, there is an emotional core to be found after all that pounding of hot metal. A big-talking knight with a self-professed destiny for greatness is seen to be a cowering, inept ne’er-do-well. He returns to the shop after a mighty battle with his sword spotless, as if unused. Your precocious apprentice takes this as a sign of his immense skill; when he realizes the knight is a phony, the reveal isn’t played for laughs but as an occasion for real disappointment.

Each of the recurring Hero characters have some kernel of truth about them to be unraveled. It would’ve been easy to write each story as a total gag, winking the whole way. But sincerity often cuts through the bluster. “All things given form wither and fade,” says a Grandmother, questing for her lost longtime husband. Earlier, your boss rebukes another hero’s search for a potion that grants immortality. “The reason life has meaning is because there is death.” Then a pair of twin acrobats will enter the shop, boasting of defeating a monster while balancings pots of hot tea on their heads, and the crazy train will roll on.

This mix of humanity with the bizarre led to a furious need to see what happened next. The first few hours I was underwhelmed by Weapon Shop’s mix of rhythm-based crafting and text-adventure story threads. But at some point near the midway point I couldn’t put the game down. There’s an accelerated day/night cycle, where the shop closes up and you save, only to thrust you back into the action come sunrise. And each morning I’d be about to set my 3DS down when the door chime rings and in bursts the pirate who’s off to rescue her lover, kidnapped by some foul beast known to sacrifice innocents.

“Sure, I’ll make one more weapon,” I told myself, but while polishing the steel I read up on the ongoing quest of a prior customer who bests their opponent with a fatal blow. Soon they’re back in the shop to return their spiked club forged with chromium ore. And by the time you finished your conversation with them, the Pirate has returned for her weapon. I couldn’t turn the game off now, could I? Especially with hints of her lover being a conniving two-timer…

Weapon Shop de Omasse is that best kind of bad.

The last half of the game I binge-consumed, my gluttony worthy of a Netflix-equipped Breaking Bad marathon. The actions were simple enough not to think too much while reading the next twist in the narrative. The jokes kept my endorphins juiced; the sincere digressions kept me emotionally attached. Weapon Shop de Omasse is that best kind of bad: a soap opera filled with impossible characters you can’t help but watch.

That these tales reside within a videogame, itself housed within the frame of another fictitious videogame, speaks to the medium’s growing maturity. This could have been a self-referential mess. Instead, these PoMo underpinnings are a foundation upon which compelling moments are shared, in a way possible only within a game. This isn’t exactly Truffaut’s Day for Night, or Allen’s Annie Hall. But it doesn’t have to be. When your samurai customer falls from grace and curses his “dismal miscarriage of a life,” you can’t help but laugh at the horrific image, as you’re reminded that in this game and others, an extra life is but a button-press away. We should all be so lucky.