What happens to the young, retired stars of esports?

When Dennis “Thresh” Fong was growing up, there was no such thing as a ‘professional gamer’. He was sixteen when he started playing DOOM (1993), but wasn’t competing for anything other than the thrill of victory. Aside from hustling chumps at the local arcade, nobody was making money by playing games.

“A professional gamer is anyone who makes money, even winning 10 bucks on a Street Fighter game at Seven-Eleven,” joked Nick Allen, the panel moderator of “The Professional Gamer” at GDC 2016. That notion should seem quaint; at the Capcom Cup in 2015, the final prize pool for Ultra Street Fighter IV (2008) was a quarter of a million dollars. The constant influx of money esports have enjoyed year after year is thanks in no small part to Fong himself, who the Guinness Book of World Records recognizes as the first professional gamer. In 1993, though, Fong was just a 16 year old who was really, really good at DOOM. So good, in fact, that the Wall Street Journal called to ask him about it.

“My life was accelerating at this rapid rate”

“I was in my pajamas one morning when they called,” said Fong. “They wanted to do a story about online gaming, and they heard that I was one of the better players.” Though he’s 39 now, with several businesses under his belt that he funded from his winnings and endorsement money, Fong still hasn’t forgotten that incredulous feeling: the first time he was seriously recognized for his abilities. Within months of that interview, Fong was competing in professional tournaments and enjoying lucrative sponsorships. The change, he said, was hard to believe. “I went from dragging a 40 pound monitor to LAN parties to getting paid thousands of dollars to make appearances,” he remembered.

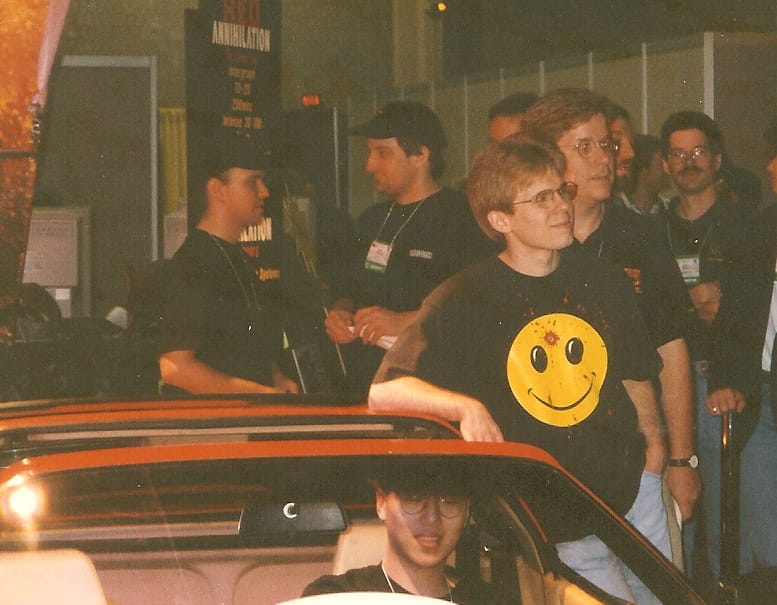

Dennis Fong sits in the Ferrari 328 he won from DOOM programmer John Carmack at E3 1997, via VentureBeat

While Fong may have been the first, he certainly wasn’t the last. Most of the panelists had similar stories: Stephen “Snoopeh” Ellis, former player for the League of Legends (2009) team Evil Geniuses, grew up in the small town of Stirling, Scotland. One day, he got a phone call from SK Gaming asking if he wanted to fly to China to play League of Legends. He was, at the time, not old enough to legally drink. Soon, he would be making six figures as a professional player. “My life was accelerating at this rapid rate,” said Ellis.

But even with the wild and sudden success Ellis and his fellow panelists experienced, they were all aware of the impermeability in their current position. Most of esports’ professional players retire by their mid-20s. Ellis dropped out of college to pursue professional gaming; he wasn’t certain what life would look like after League of Legends left him behind. “You have to think about what you’re doing with your money,” Ellis said. “Within 10 years of being out of the NBA, a lot of players go bankrupt. Prepare for the future.”

not all esports athletes end up so lucky

These concerns weren’t unique to Ellis’ game. Tricia Sugita, a professional StarCraft II (2010) player, described establishing her backup career in case the well dried up. “I was a business software consultant,” she said. “Have a backup plan,” urged Robin Johansson, a professional Counter-Strike (2012) player.

Their caution has paid off; everyone speaking in “The Professional Gamer” has skillfully transitioned into life after professional gaming. Of course, not all esports athletes end up so lucky. All the panelists shared stories of blindingly fast success, but implicit was the fear that everything they had gained could be taken from them just as quickly.

Check out our ongoing coverage of GDC 2016 here.