The Oculus Rift and a pair of headphones sit on your head almost like a motorcycle helmet, and similarly put you a step back from the world. Rather than getting zen on a mountain highway with just you and your hog, virtual reality, which is currently being led by Oculus, completely takes over your primary sensory input. I had the pleasure of this experience at Microsoft’s NERD center in Cambridge, Massachusetts, at an Oculus-oriented “Virtual Reality Meet-up”; part public tech demo, part job fair, all draped with the cotton-candy skyline of possibly the final temperate Northeastern afternoon of the year.

The event drew out tech luminaries from the growing community around Kendall Square, including MIT’s Game lab along with local indie developers Dejobaan Games, 82 Apps, Defective Studios, and several other groups. They excitedly shared their Oculus Rift developer kits and beta software with the public, press, potential employees, and investors alike. Games weren’t the sole focus, but they were advertised as a large slice of the pie, so I attended with the question in mind: is there a game that necessitates the Oculus Rift? Is such a game even possible?

I attended with the question in mind: is there a game that necessitates the Oculus Rift? Is such a game even possible?

This is an unfair question, if we’re being honest. For all practical reasons it’s too soon to make such calls; prices and software are still in flux. Almost every game on display in the NERD center was developed before the Oculus Rift was on the table, though each developer praised the ease with which they were able to adjust their PC/Mac games for the device. Oculus VR Founder Palmer Luckey admitted in his keynote (many speakers were shifted around as a result of the shooting at LAX during the week prior) that not every game is appropriate for conversion to VR. Which is to be expected; VR isn’t right for every game just as the PlayStation Move or the Kinect aren’t right for every game. However, there were several folks at the NERD center who felt that the Oculus Rift fundamentally expanded upon their software, and that maybe even, serendipitously, they were developing games for the Rift before they even knew it existed.

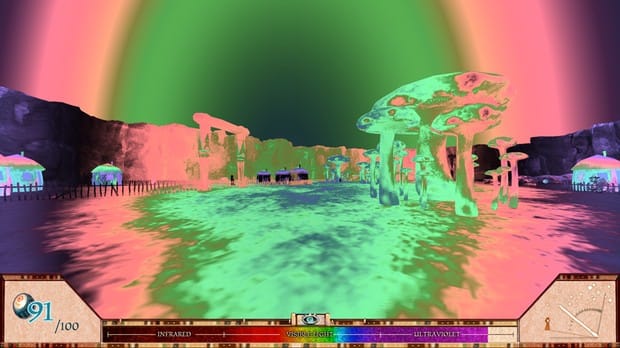

I started with the MIT Game Lab folks. They brought an OR-ready version of A Slower Speed of Light , an edutainment piece meant to simulate the experience of light-speed travel. This game perked ears a year ago before VR was on the table, but the Game Lab saw instant appeal in the Oculus Rift. They’re working to get the game down to a 30-60 second virtual reality experience, ideal for use in a museum setting where longer playthroughs aren’t really an option. The Rift changes, and enhances, the light speed experience—you’re immersed in the shifting color spectrum and expanding landscapes, twisting your neck rather than your periphery. It’s hard to say whether it’s any more or less fascinating an experience within VR, or if it’s just the VR: this game was conceptually fascinating for a spell a year ago, and remains so for many of the same reasons. The Rift doesn’t change those fundamental properties, nor sufficiently convince your brain that you’re travelling at the speed of light.

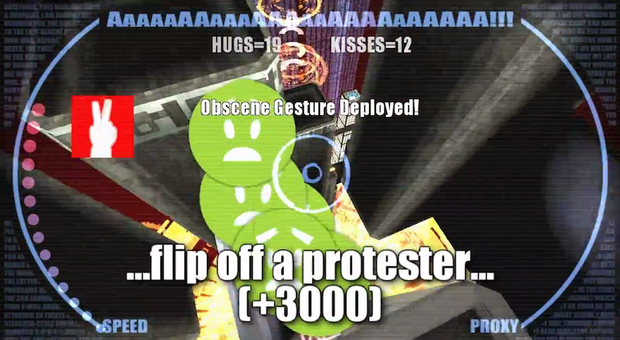

At this point, that sentiment could, and is, expressed for almost all available VR options. Is it the game, or is it the novelty of VR that I’m appreciating here? I asked Ichiro Lambe of Dejobaan games, who brought his Oculus Rift ready version of the impossible to search for “AaaaaAAaaaAAAaaAAAAaAAAAA!!!” to the NERD center, if the novelty wears off. He’s spent many hours under the goggles and believes that it’s as immersive each time, though the base-jumping simulator has been available for several platforms long before they got their hands on the Oculus Rift. Lambe says that this game was made for VR, if a little preemptively. He’s not full of smoke on this; it’s a totally separate experience to stare down at the ground rather than forward at a screen, attempting to kiss the passing buildings without obliterating yourself by falling into them. But for all your head-twisting and depth perception, it’s hard to ignore one of the basic limitations of the Oculus Rift: it’s a headset, for your eyes and maybe your ears, leaving behind your other major senses. Your eyes say that you’re falling, but your fingers are still clicking WASD on a keyboard.

The last game I had a chance to try out was also the first to give me a hint of “simulator sickness”. None of the presenters had trashcans prepared for worst-case scenarios, but the topic of vomit wasn’t shied away from. Erik Asmussen of 82 Apps, who brought his in-beta game Disco Dodgeball, hadn’t experienced full-on nausea himself, but recognizes the possibility. His game was the first where I felt deeper hints of true disassociation from reality. But it was also the one I spent the most time with, and the last I played.

The game takes place in a neon-drenched arena that immediately brings to mind both Tron and laser tag. You and a red exclamation point-shaped robot square off with glowing dodge balls, and the standard rules apply: you have to account for the physics of throwing the ball, not just shooting it like a firearm; you can catch thrown balls to instantly defeat the thrower; and as points are earned, more players enter the arena. Since I wasn’t on rails, and was engaging other players (or bots), the VR really kicked in here. I twisted and turned my face in constant fear of an oncoming ball, running around like a terrified lab rat, and eventually lost, but breathlessly. Coming out of the headset I felt it in the pit of my stomach; not full-on sickness, but rather a bit of eye-strain and disassociation from going in and out. People claim similar experiences with the 3DS though, which has never bothered me, and Erik added that it’s the kind of thing you get used to.

But if we tackle one sense at a time as thoroughly as the Oculus Rift, the potential is there.

Palmer said as much as well in his keynote, and acknowledged the challenge of selling a product that one must acclimate themselves in using. Limitations aside, the Oculus Rift is a singular experience, and there are plenty of videos online of people deep in their simulations, lost in wonder, mouths agape and eyes obscured. The Oculus Rift completely overtakes your sense of sight, and if done well, your sense of hearing. In doing so, however, it becomes immediately apparent how tied together all of our senses are. When your eyes are fooled, your sense of touch looks to compensate, along with your inner ear and balance. The brain often takes any unnatural input as a sign of poison or damage, and can render the user fairly uncomfortable, to say the least. There are so many variables involved, beyond sight even, that the holodeck experience is still decades away. But if we tackle one sense at a time as thoroughly as the Oculus Rift, the potential is there.

Potential, however, isn’t always enough. The Oculus Rift isn’t commercially available yet, and so far most of the software for it has been ports of already perfectly playable games for other hardware. I did not see the one that requires the Rift to convey an emotional experience unavailable through any other means. But my interest in piqued; the Oculus Rift is an interesting experience, and the consensus around the event was “it’s crazy right?” Running on PCs and Macs through software converted for VR in under a weekend for many, the challenges are not technical, but creative. The same could be said for any new console or hardware; I hardly expect that there will be a game that requires the Xbox One and only the Xbox One for reasons other than licensing. It’s clear that the developers involved are deeply invested, the hardware makers are passionate, and they all dream big about what the Oculus Rift can offer. As the device is released developers experiment, particularly within the independent games world, then VR’s capital will truly be assessed.