What videogame RPGs could learn from Community

You’ve probably seen that one episode of Community. It’s impossible to talk about tabletop role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons without mentioning it. A lot of people’s introduction to D&D was hearing Abed say, “This is a role-playing game. It takes place entirely in our collective imagination. I tell a story and you make choices in the story.” Which is excellent, because that’s the best introduction to D&D you could have: it gets to the point, which is a rare virtue. Playing the videogame descendants of RPGs, it’s unlikely you’ll hear an introduction so succinct.

Take Might & Magic X: Legacy, for instance, Ubisoft’s 2013 resurrection of the classic series. The introductory cutscene is four minutes long and begins with someone telling you about a dream they had, then wondering about the nature of dreams, before meandering through ancient history and politics for a bit. Only in its dying seconds does the narrator remember to mention anything about you, some hero on a quest or whatever, which is completely unrelated to everything you just heard and saw.

videogames are in love with their own lore

When I was 14 years old and running my first game of Warhammer Fantasy Role-Play for my high school friends (both of them) I made a similar mistake. RPG scenarios typically begin with a chunk of boxed text, three or four paragraphs of setup you’re expected to read off the page to the people sitting at your table. I did that, then looked up and realised they were about to fall asleep before we’d even started. There’s something about the “reading out loud” voice that turns us into kids being read bedtime stories, and out go the lights in our heads.

Abed does not read out the boxed text. He summarises it in a few short sentences, and at no point does he say anything like, “This story begins with what we now call Uriel’s Deception. During the fabled Elder Wars…” Instead, he sets up our heroes and their adventure and he starts, and he does it while making eye contact with his players. I could have cheered at that scene when I first saw it, because it’s exactly how a good Dungeon Master runs a game. (Yeah, Dungeon Master is what they’re called, and, yeah, it is weird.) Imagine if Skyrim started with something as brief as, “You’ve been mistakenly arrested alongside a group of revolutionaries you’ve never met. A soldier is leading you to the chopping block. GO!”

But videogames are in love with their own lore, and whether it’s the intro narrator or the opinionated bartenders in Deus Ex they will lecture you about it at length. In tabletop games we call this stuff the “fluff” to differentiate it from the rules, which are the “crunch.” There’s an implied judgement in those names, a suggestion that crunch is the good stuff, the real business, while fluff is airy, lightweight, inessential. Some people— the kind who care about why this fantasy land’s wizards are different— object to the word “fluff” for those reasons. I suspect those people of having rubbish pillows. Fluffiness is delightful, and I like fluff in the right places.

the fluff is important

The rulebooks for tabletop RPGs place their fluff and crunch in alternating layers, like some kind of delicious pastry with cream in it and possibly also nuts. Often they weave the two together until it’s hard to tell them apart. Getting back to that teenage game of Warhammer FRP, part of what made my droning boxed test introduction redundant was how well the game had already communicated its setting, and, importantly, its tone. Characters in Warhammer FRP are defined by careers, which are like the classes in D&D but more restrictive and specific. You might be a Noble, but you might also be a Footpad or Rat Catcher or Servant. It doesn’t have classes, but it most certainly has a class system, and your odds of being at the top are low.

Obsidian’s latest game Pillars of Eternity differentiates its characters by adding subraces, cultures, and backgrounds to its classes, so that you can decide your Human Fighter is actually a Meadow Folk Dissident from The White That Wends. But understanding what each of those things mean involves reading a paragraph of description and hoping it will be relevant in the actual game. Looking down at a Warhammer FRP character sheet and realizing you are basically playing Baldrick from Blackadder is instantaneous.

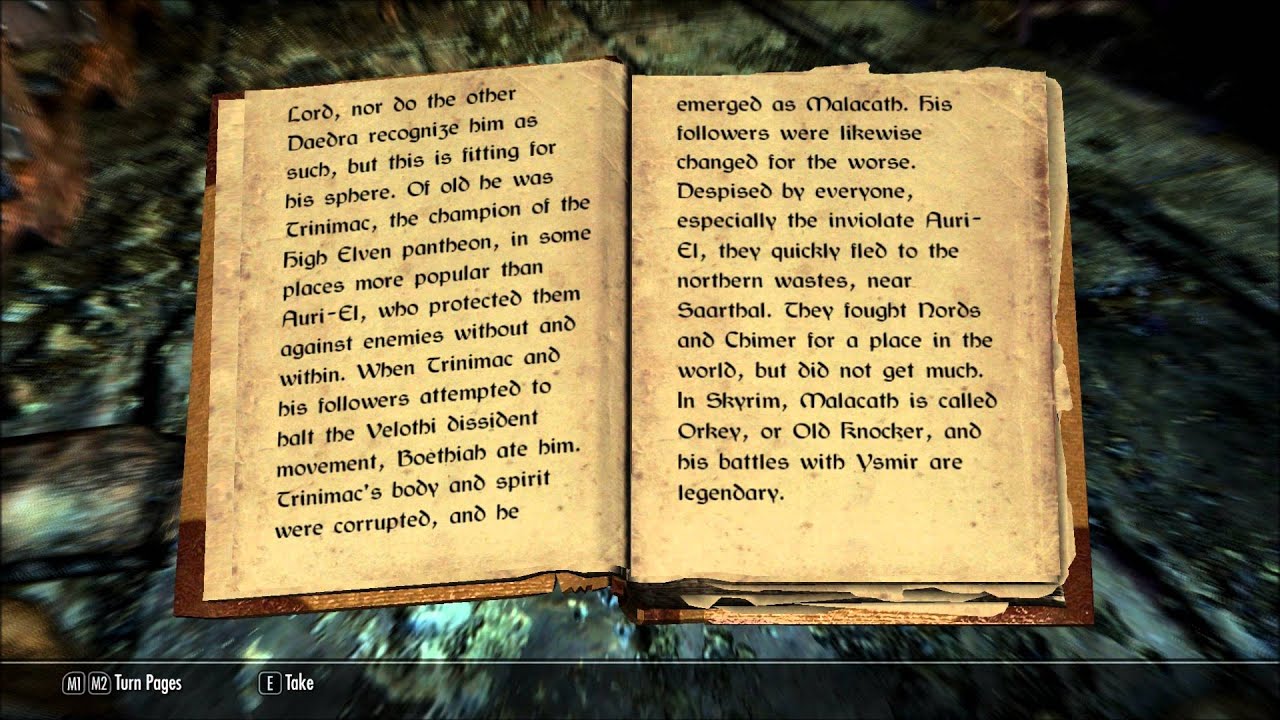

RPGs don’t just front-load themselves with heavy dumps of backstory at the start, however. They keep it up the whole way through. Each Elder Scrolls game hands you books as loot, and even as the kind of player who will skim The True Nature of Orcs with a cup of tea when I need a break from shooting arrows at giant spiders, there’s no way I’m ever reading all of them. There are 470 books in Skyrim alone. Mostly I just sell them, and only realise which ones are important when I’m not allowed to flog off a particular one because a pop-up tells me it’s a quest item that somehow relates to one of the 20 tasks in my journal.

Tabletop horror RPG Call of Cthulhu has the perfect solution to this problem. Its campaign Masks of Nyarlathotep, a globe-trotting pulp tale set in the 1920s, popularised the idea of using props for player handouts. As the investigators hunt for clues from New York to Nairobi they receive newspaper articles, letters, diary entries, telegraphs, even a matchbox left behind in a hotel room. Each is unique, the letters composed in different handwriting and the news stories written in different styles based on whether they’re from the New York Pillar/Riposte or the tabloid Scoop. While nothing in a videogame can compare to sliding a matchbox across the table and watching players turn it over to read the address of the bar it’s from, the individuality of each handout makes them— and the information they contain— unforgettable. Meanwhile, the books from The Elder Scrolls are almost all written in the same font, as if copied by monks in a scriptorum with access to MS Word.

Faced with RPGs that drown you in fluff, it’s easy to rail against it, to long for the simplicity of games that just give you a gun and point you at some zombies. But the fluff is important, as everyone who has ever had a player yawn and say “What are we doing in this dungeon anyway?” knows. Context gives players motivation— it just needs to be distinctive enough to remember and subtle enough to not feel like homework. When Abed leads his study group in a game of D&D nobody realises they’re learning anything: they just have fun.

Header image courtesy of Wizards of the Coast.