What’s Happening?

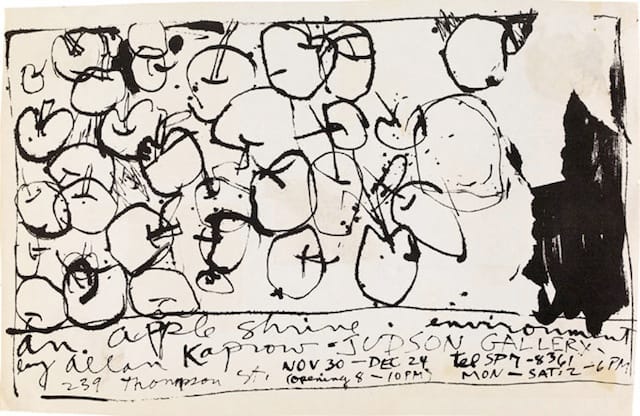

Make your way through a labyrinth of shredded newspaper, chicken wire, ripped cardboard, and crumpled newspapers. In the center of the maze is a softly glowing, sanctum-like room with a three-tiered wooden altar hung floating above the floor. On the altar is a pile of real apples mixed in with their plastic simulacra. A hazy miasma of apple scent hangs in the air. The choice that faces you: Take a plastic apple and hold onto it forever, or reach for a real apple and complete the sensory experience by tasting the apple, be that taste ever so ephemeral.

An Apple Shrine, an “Environment” created by 1960s conceptual art pioneer Allan Kaprow, sounds a little like a videogame. The piece’s immersive quality (it expanded to fill an entire gallery space and would have taken a fair amount of time to navigate), interactivity, and final forced decision might as well be a part of some postmodern Zelda game in which the player is turned into an art viewer, and the dungeon boss replaced with a philosophical conundrum. The process of interaction—penetrating farther and farther into a mysterious tiny universe, a feeling known well by any gamer—is present in the artwork, as is the traditional narrative arc of a game: Make your way through the temple and you are rewarded.

Kaprow was a pioneer of interactive, experiential art. His “Happenings,” which followed Environments like An Apple Shrine, were one-off artistic events that now might sound like a cliché of the ’60s, with strange dances, music, and performative painting occurring right within the midst of awestruck audiences. Yet these works remain a defining avant-garde touchstone. Reacting to the stiff, theory-based ideology of the Abstract Expressionists, Kaprow and his Happening cohorts (including younger artists like Claes Oldenburg and Lucas Samaras) liberated art from the canvas and made their viewers not just intelligent consumers but co-creators.

The artists provide the structure, while the viewer provides the dynamic experience—the life that makes a piece of art truly powerful. In the collaboration between creator and viewer, this participatory art was much like a videogame: audiences had to make of the work what they would, activating it with their own decisions as one would activate the world of Skyrim, searching out new sensory moments by moving into new spaces, testing the boundaries of the situation, and exploring freely. In order to experience art like Kaprow’s, the viewer must first become a player.

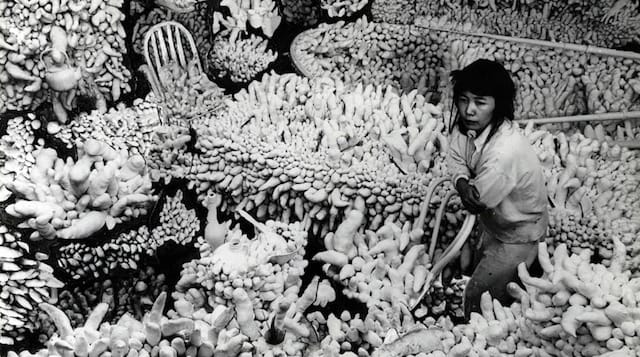

Happenings by artists like Kaprow and Yayoi Kusama enabled audiences to take part in performance art. Kusama’s environments in particular invited viewers into surreal, bizarre spaces unthinkable outside of an artwork—check out her Compulsion Furniture environment, in which a standard living-room setup is covered in phallic protrusions. The Japanese artist also toyed with the idea of virtual space in her infinity rooms, enclosed galleries covered in endlessly reflecting mirrors dotted with lights for an overall effect that might bring to mind a warped version of Portal.

Instead of putting canvases on walls and leaving it at that, artists in the ’60s and ’70s pioneered immersive installations that restored agency to viewers. For a transcendent experience of pure agency, look to James Turrell’s light chambers: smoothly curved, monochromatic rooms that appear to stretch out into the distance forever, like borderless horizons. A predecessor to installation art, Kurt Schwitters’s Merzbau is what would happen if a game of Tetris exploded in a small space, with fractured polygons plastering the walls. Even early Dutch abstractionist Piet Mondrian got into the game, covering the entirety of his New York City studio in his characteristic geometric shapes. These works all present spaces for viewers to explore at will—with much less narrative than an open-world videogame like Fallout 3, but conceptually alike.

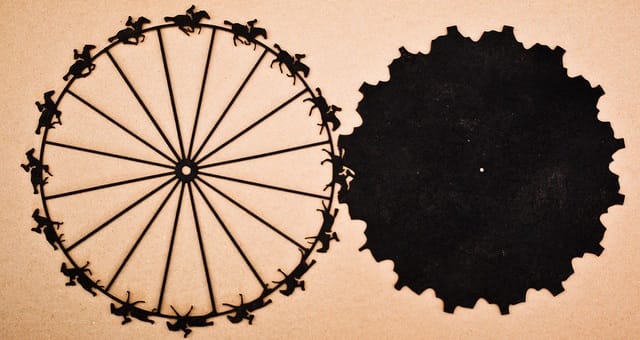

Within the same ’60s and ’70s New York City milieu as Kaprow and Kusama were the Fluxus artists, a group who named themselves after the Latin word for “flow.” Taking their cue from the Dada movement in the earlier half of the 20th century, Fluxus artists were strongly anti-commercial and played with ideas of the absurd. They created small activities and games for viewers that were meant to shake them out of their daily stupor, facilitating small moments of aesthetic and emotional awareness amidst what they saw as a dull cultural climate. Yoko Ono’s 1971 A Box of Smile is simply a box with a mirror embedded in the bottom. It’s a whimsical bit of trickery that prompts a reconsideration of an everyday moment, like Katamari Damacy’s fantastical re-imagining of domestic objects and mundane scenery.

It just might be that art is doing a better job than mainstream videogames of using interactivity as a tool.

In his 1958 essay “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” Kaprow first outlined the idea of the Happening as a distillation of everyday life, an uncovering of the normal. He suggests that this uncovering should be the goal of the day’s young artists: “Not only will these bold creators show us, as if for the first time, the world we have always had about us but ignored, but they will disclose entirely unheard-of happenings and events.” He goes on to describe the possibilities in surreal, flitting poetics: “An odor of crushed strawberries, a letter from a friend, or a billboard selling Drano; three taps on the front door, a scratch a sigh, or a voice lecturing endlessly, a blinding staccato flash, a bowler hat—all will become materials for this new concrete art.” Kaprow turned out to be right.

Videogames are of course accomplishing this goal of shining a new light on the world around us with creations like Pokémon (insect collecting) and Braid (the lasting consequences of our mistakes). Will birds ever be the same now that they’ve gotten Angry? I think not. It just might be that art is doing a better job than mainstream videogames of using interactivity as a tool, entertaining and attracting viewers, but also forcing them to reconsider their relationship with technology on a fundamental level. Casey Reas’ projections of swirling, abstract patterns sense where their viewers are within a space and shift accordingly, creating a whole new kind of generative performance art. Kyle McDonald’s project People Staring at Computers (2011) appropriates Mac computers, that technology we all know so well, and takes over an Apple store’s worth of webcams, taking snapshots of the anonymous users trying them out. If only videogames could attain that level of critical self-awareness.