Why is Kill Screen running review scores again?

You are reading this big header and asking: Why is Kill Screen running review scores? Didn’t you already declare them dead?

The answer is: yes, we did. They were really truly killed and dead and now they’re back. They’re big and they’re stuck right on the top of the review. There are both colors and numbers involved. I want to explain why, and I will by the time we’re done here. But first, I want to talk about Ol’ Dirty Bastard.

Ol’ Dirty Bastard released his first album in 1995, right in the oft-cited Golden Age of Hip-Hop. It is often considered one of the best albums of that era. It begins with just under five minutes of the emcee mewling over canned crowd noise and synthesized strings; by the end of the first track, he is, I think, crying. Things go off the rails from there, with arrhythmic beats matched to atonal singing. On “Brooklyn Zoo II,” the beat changes up at least five times across the span of seven minutes; at times, he is screaming, crooning, rapping, and talking at the same time.

I want you to imagine, for a minute, that somebody from 1945 traveled through time to 1995 to listen to that album with you. What would that person think? The popular song of 1945 was called “Shoo-Fly Pie and Apple Pan Dowdy,” and, while that sort of sounds like an ODB song title, the song itself does not. I want you to imagine what that person would think of Ol’ Dirty Bastard; I want you to imagine the conversation that would ensue if you were to ask this person if ODB were music.

Okay, so: freeze frame on ODB in hot ‘95 mode—flash forward to February 2011, when Kill Screen started publishing reviews, and with them an article a lot like this one explaining why. That article acknowledged, first, the inherent strangeness of the endeavor:

You’ve heard it all by now. Game reviews are buyer’s guides. Critics tick off a checklist of graphics, sound, “gameplay,” and if you’re lucky, story … You and I may reach the same ending, but we’ve had vastly different experiences. You used the sniper rifle; I favored grenades. You care about the side quests; I skipped the cut scenes. You flirted with Leliana, and I got dumped by Alistair (and will never forgive him). And as for multiplayer—how can we compare notes on that?

But reviews of any sort are, I’ve always fancied, a sort of cultural necessity. Any piece of art, whether it’s a cheese danish or a prog-rock album, is a cultural action, sometimes a very public one, and a critic is just publically responding to that action. A re-action, if you will. If that critic is a twit, people will find the opinion stupid and move on; if that critic is good, has a thoughtful, informed opinion about the work and has conveyed it engagingly, she has done her job at the basic level. Good criticism, though, can be more than that: it can be its own sort of action. That was the hope in February 2011:

Reviews can represent a snapshot in time, that moment when a piece of technology and art finds human meaning. Let’s treat reviews as ends in themselves, not as means for making smarter choices for buying new product. (…) We hope you’ll seek out Kill Screen reviews because, like a beautiful print magazine, they’re nice things to read. If we succeed as critics, they will also give you insight into games.

Six months later, and after some unconscionable spell playing Duke Nukem Forever, that idealism was shot. None of those things from the original score-justification had changed but the absurdity of the endeavor had only become more clear. Pinning all the four-dimensional complexities of a piece of art onto a one-dimensional scale is limiting, reductive, foolish. And, as Kill Screen founder Jamin Warren said in that Duke Nukem review, Kill Screen had succeeded in the ambition of creating cultural actions. But that only exacerbated the issue: “The appearance of math,” he said, “was only clouding the pool.” And so our review metric was shattered, never to be used again.

As a writer, assigning a review a score sorta hurts. I know: woe unto the critic, right? Critics are, I realize, an easy punching bag, a self-serious lot that, as the stereotype goes, don’t like anything fun. Both artist and public, it is sometimes said, could do without the critic. Music writers oft cite the oft-missourced quote that “writing about music is like dancing about architecture”; they like this quote because it encapsulates the public disdain for supposedly haughty critics but also because it gets at the inherent weirdness of their work. Sticking a number on the thing just calls attention to this weirdness; and, while a lot of critics have gotten around this by not adding a score, others have stuck firmly to their guns (or their stars or their numbers or thumbs). Embracing the weirdness, as it were.

And that’s just the thing. Criticism is only getting weirder, at least vis a vis videogames. Writing and videogames are completely incongruous, and that’s because everything and videogames are completely incongruous. As the form develops and matures and regresses, sometimes within the span of a single work, the need for solid, harder criticism increases. The Duke Nukems ain’t going away, in other words. We can argue whether scores are necessary for film or music or cheese danishes, but because videogames are in a state of flux, in fact because they are not suited for a binary rating, they actually require a clearer public re-action. The original actions, the games themselves, are too weird, too various. They are mutating, as popular music did so violently in the fifty years that birthed psychedelic rock, soul, punk, metal, fusion, house, and, eventually, Ol’ Dirty Bastard.

What we need, then, is not necessarily lower scores or angrier critics—although those would be nice—but more solid ones: we need braying, iconoclastic voices just as much as we need clarion, establishment voices. We need everything in-between: we need lily-livered panderers, moderates, and feckless joykillers in equal measure. And we need scores to plant these opinions in the ground. Videogames are, yes, fungible experiences, but our reactions and our scores are not. While a monsoon of rhetoric and money and activity swirls around we can grip our 73s and our 32s and say: Here is what I thought, not more or less but exactly. Otherwise how in the hell can we act like this is a unified medium? How can we even begin to say that all of these guns and fields, these tone poems and war recreations, these silly digital toys and these alternate realities, are roughly the same experience? That they matter at all depends upon the idea that they are, in some manner, alike.

Numbers, we think, are a start. We urge you to agree, or not.

Header image A Painter at his Paint Box by Adolph Tidemand

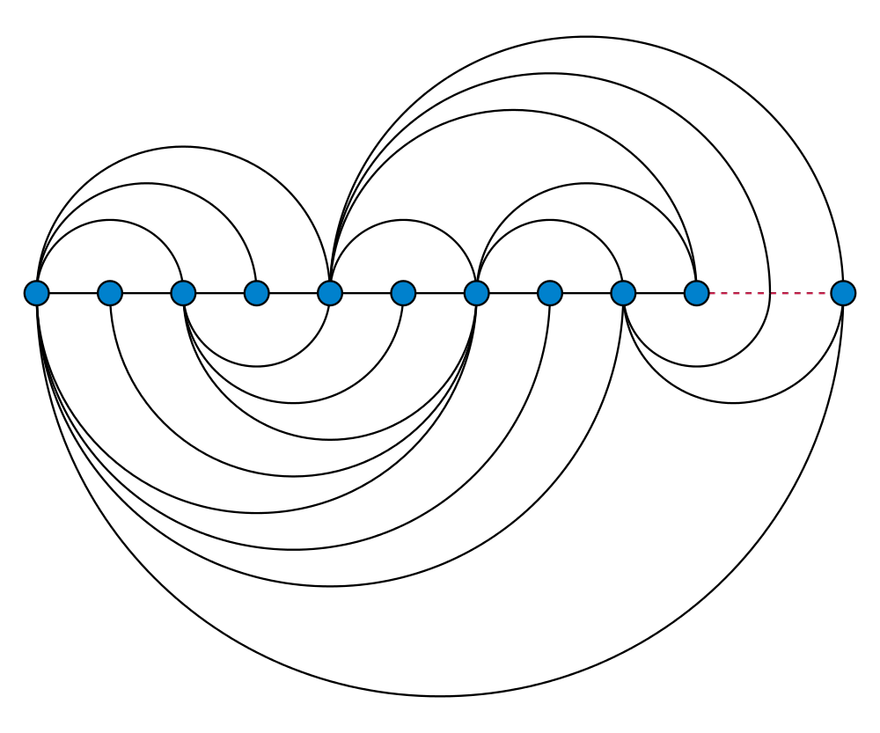

In-line image A linear embedding of the Goldner-Harary graph