This could be a big deal. But we’ll get to the future soon enough. First, a glance to the past.

News of Nintendo’s demise has been swirling recently. And by “recently,” I mean since 1981, when warehouses were filled with unsold cabinets of space-shooter Radar Scope, a popular Japanese game that failed to ignite the interest of American arcade owners. (The units were retroactively programmed with a new game, about a mustachioed man’s attempts at saving his girlfriend from a barrel-tossing ape. It did okay.) But really, Nintendo was done for when their earlier forays into instant rice, taxi service, and “love hotels” failed to resonate with customers in the 1960s. In fact, the company was likely on its last legs in 1949 when Sekiryo Yamauchi, the company’s second-ever president and the founder’s son-in-law, died, leaving the 60-year-old business in the charge of his twenty-one-year old grandson named Hiroshi. (He did okay, too.)

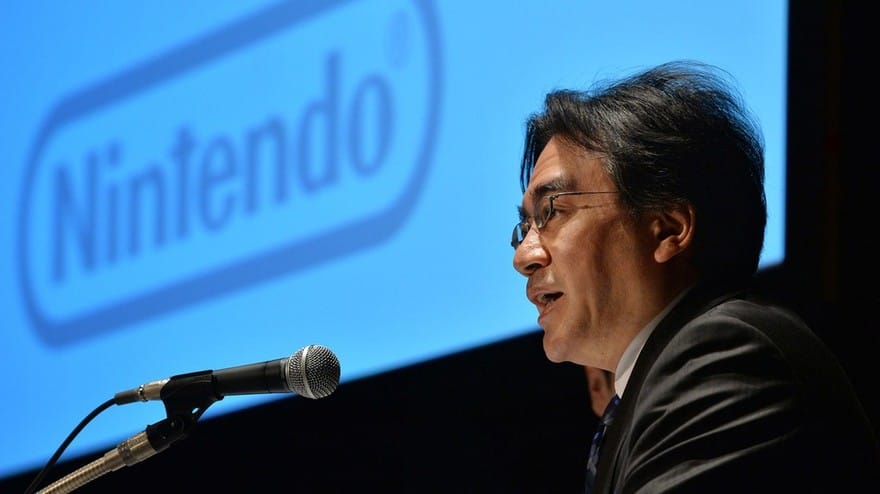

The newest head on the chopping block belongs to Satoru Iwata, president of Nintendo Company Limited since 2002, and the first and only leader given the reins from outside of the Yamauchi family since its founding in 1889. Under Iwata’s watchful eye the company has performed several miracles, doubtless familiar to readers already. First it introduced a strange, two-screened handheld device called the Nintendo DS that played games but also gave you a virtual puppy to pet or challenged you to daily math equations. The device was underpowered and built, it seemed, for an audience that didn’t even exist, providing answers to questions nobody thought to ask. It has sold over 150 million units worldwide.

Then came the Wii. Strange, check. Underpowered, check. Answers to unasked questions, check. It did okay, too, with lifetime sales to date just passing the 100 million mark.

All this success brought a huge amount of money into Nintendo’s coffers. But more than that, these products and their unlikely widespread appeal expanded the notion of what a videogame could be, and with that new definition came millions of people never exposed to Nintendo before. Surely new and improved systems from The House of Mario would sell to all these millions of new fans! Iwata’s position as sage and miracle-worker was all but guaranteed.

What he said hints at the beginning of an overhaul in strategy, the formation, indeed, of an entirely new kind of experience.

Until it wasn’t. The last three years have brought on diminishing returns and with it, vocal opposition. Their new systems, the Nintendo 3DS and the Wii U, have either been slow out of the gate or seen as an utter failure. All sorts of people, from investors to analysts to fans, have been quick to move Nintendo away from what sustains them and into the newest, latest success: Make a phone. Make games for phones. Use a phone to call somebody who knows what they’re doing and, you know, do something.

Nintendo is about to do something. But it’s not what you thought they should do. And the repercussions may well echo for decades, just as Donkey Kong saved and ignited a fledgling games company into the world’s largest.

On January 30th, Iwata gave a presentation outlining the company’s future plans, both in the near- and far-term. Resident news-man Jason Johnson has already listed details of what to expect: the promised release of software for current hardware, fixes or upgrades to these system’s functionality, and a more lenient stance on licensing their characters. All well and good. But then the president revealed Nintendo’s plans beyond the present calendar year. For a company whose main directive has wavered little in thirty years, what he said hints at the beginning of an overhaul in strategy, the formation, indeed, of an entirely new kind of experience.

“We will definitely maintain dedicated video game platforms as our core business,” Iwata said, “but…” and here, on the online English transcription of this report , a reader clicks to see the next page, and that time is spent wondering what in the sam-hell is on the other side of that conjunction, before the next page loads: “… but we will also take on the challenge of expanding into a new business area.”

This “new business area” is a vague but fascinating promise. In short, Nintendo is moving into a parallel space alongside its seasoned and well-loved (but oft-maligned) videogames. Iwata’s presentation continues with fragments of hope, of shortened blips taken from longer spells cast behind the curtain.

“I have run Nintendo with the belief that the raison d’etre of entertainment is to put smiles on people’s faces around the world,” he says, before adding, “I think now is the time we need to extend the definition of entertainment.”

Smiles only last so long. Muscles tire; our attention shifts. Nintendo aims to move beyond our emotive face and focus on the source itself: how well we live in the first place. “We decided to redefine our notion of entertainment as something that improves people’s quality of life in enjoyable ways,” Iwata continues. This phrase (shortened to QOL for the duration of his talk) immediately expands Nintendo’s target beyond that of what’s been expected for a videogame company. In a way, it’s the more proactive version of Google’s self-professed motto: “Don’t be evil.” Here, Nintendo is hoping to solve the related problem: “How can we be better?”

Nintendo, once again, has decided to zag where everyone else thinks it should zig.

Their solution? Yet to be fully disclosed. But Iwata dripped tantalizing details that may well flourish into the next unforeseen sensation. In a landscape obsessed with wearable technology, Nintendo hopes to base this new health-centric vision on something called “non-wearables.” The term itself feels like a joke, the nonsensical feint of a sore loser sick of being bullied. Oh you drink water to stay alive? I’ll drink rocks! You breathe oxygen? Ha, I’m going to breathe paint fumes! The future is wearables, you say?… Non-wearables it is! Nintendo, once again, has decided to zag where everyone else thinks it should zig.

The disregard for trends even pops up in their presentation slides. After all the hullabaloo about Nintendo joining forces with mobile, a slide labeled “Expanding our Business in a new Blue Ocean” shows four ovals, one after the other: Console (picture of a 3DS), Mobile (picture of smartphone), Wearable (picture that resembles Google Glass). A line extends from Console to the last oval, called Non-Wearables, the arrow arcing over the middle two, with a cheeky caption stating their goal in the terms of playground warfare: “Leapfrog Strategy.” This last oval’s lines are filled in with a soothing gradient of blue. There is no picture of the next big Nintendo product. Only the promise of something lurking under waters untapped by others.

We’ll know what’s there later this year; Iwata promised further details before the end of 2014. But to shrug off this new vision as a Mario-branded pedometer or Yoshi-inspired fruit juice is missing the point. Nintendo realizes the ground has shifted underneath them. They need to move or risk being swallowed up. They’re still in the videogame business and will be for some time. But they’re taking steps to expand how we think of them as a company. Amazon first sold books; now they sell everything. Nintendo first sold cards, then rice, then games. What’s next? We might soon find out.

The last slide of the presentation given shows two distinct paths, each describing the Nintendo of our recent past, but also of a newly revealed future. One path is labeled: “Game Platform (1983 – ) → Expansion of the Gaming Population.” The other path, the color of burnt orange, a trail about to be blazed: “QOL-Improving Platform (2015 – ) → Expansion of the Fit Population.” Each path funnels down into a single blue rectangle: “Expansion of Nintendo Users.”

Sure, that last phrase has a whiff of cult enrollment. This may all be marketing malarky. Or, if these vague notions coalesce into anything resembling a real, tangible product, Nintendo may have just promised to introduce a new form of entertainment that goes beyond smiles and, instead, allows us to become better versions of ourselves. That’s a tall order. But they’ve arisen from doomsday scenarios before. If only they can help us do the same.