The Kill Screen Review: Resident Evil 6, a devastating parable about addiction

You know by now that Resident Evil 6 is a distended disaster, a gaseous zombie of a game. Yes, it must be buried. I come not to protest the act, no, I have a shovel and am willing and able to dig.

I would like to offer a few words, though, something of a eulogy, because even the most ridiculous and offensive lives must be made sense of for the rest of us to go on living. Allowing this weird mess to pass onto the bargain shelf with just the naying and braying about “broken gameplay” and “bland environments” feels insufficient. To paraphrase Tolstoy in poor faith, bad games are all bad in different ways, and Resident Evil 6 is uniquely and unsettlingly bad, and I must try to squeeze some meaning from it.

This isn’t a “had a lot of promise” eulogy; the game is loudly inept from the beginning. One of the oldest tricks in narrative is to start with an exciting moment near the end of the story, then flash back to the beginning. Within the first ten minutes of Resident Evil 6, you smash a helicopter chassis through an apartment building, after colliding with but not being destroyed by an elevated train, after, while flying the chopper, shooting in the face a zombie that is trying to eat your partner. This qualifies as your exciting moment.

Has there ever been a blander collection of meaningless white people than those in these games?

Then we flash back to the beginning of the story, which should introduce the player to the characters and set the tone and establish the themes of the game. Instead, in the first scene, you murder the president. He’s a zombie, you see. Also, after shooting him, you cradle his head in your hands and say, “I’m sorry, Adam.” The president’s name is Adam.

It says a lot about the game that the fact that you are able to board an international flight hours after murdering President Adam is about the fifty-sixth least-coherent plot point.

Dear god, that plot! The Resident Evil series now spans sixteen years and countless games. The plot of Resident Evil 6 seems to make reference to nearly all of them, despite the fact that the youngest possible player who could have played all these games is, say, 23. Even assuming that this person exists, how can they possibly remember everything that has happened through the years and years of T-viruses and C-viruses and Mila Jovoviches?

(Also, why does the Resident Evil series have recurring characters? Has there ever been a blander collection of meaningless white people than those in these games? Who in the world cares what happens to them? No one but no one is clamoring to know the fate of Leon Kennedy and Chris Redfield. The only difference between these two, as far as I can tell, is that Leon wears a wonderful Moto-style leather jacket that looks better and better with wear and tear.)

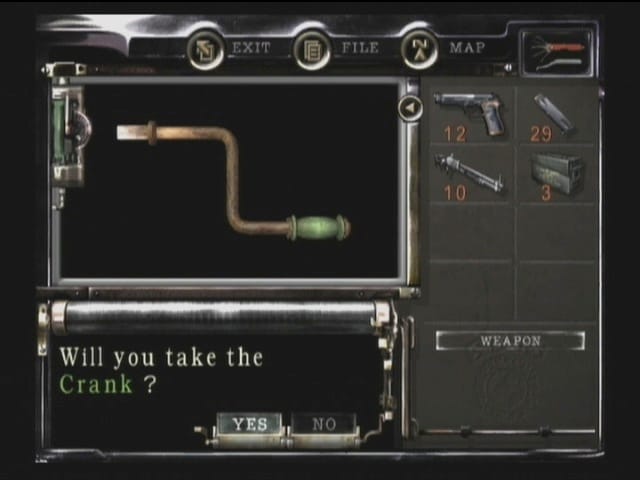

Then, about six hours in, there is a moment that makes the entire game cohere. As you run through some horribly enervated person’s idea of catacombs with your pointless, rock-breasted partner, you realize that the crank you need to open a nearby gate is missing.

“Guess what? There’s no crank,” says you.

“No crank? Well we’ve got to look for it,” Elena (I think that’s her name) responds.

“True. What the hell else are we going to do?” you admit.

Then, it struck me. Resident Evil 6 is a parable about two heroin addicts. The game is always asking: where is the crank? Can you use the crank in time? Can you avoid the monsters that are trying to keep you from using the crank? Only in the baffling, terrifying, urgent world of the smack-addled could the way this game operates make any sense. The zombies, I think, are not even zombies, just normies, the shuffling masses who don’t and will never know the beauty of a pure shot of china white! The ones who want you to have a normal job and keep normal hours and not use the crank!

Of course the struggle of two junkheads to stay flooded with their junkie reality would be over-the-top, outrageous, nonsensical.

The game’s operatic awfulness suddenly slides into focus. Of course the struggle of two junkheads to stay flooded with their junkie reality would be over-the-top, outrageous, nonsensical. The moment-to-moment gameplay often looks like this: rising tension as you look for the crank, fear that you will not be able to use the crank as you are assailed by zombies, then quiet relief and exploration after successful crank use.

The narrative that emerges from this reading is full of rich symbolism. One memorable set-piece involves trying to protect your partner from exploding Roombas. I imagined a pair of strung-out losers, terrified by the robot-vacuums they bought in a happier time while flush with dope money, terrified by the idea of cleaning up their lives.

Folks, Capcom went for it with this one. They wanted to show gamers the horrors of an escalating hard-drug habit through the power of triple-A gaming, and they succeeded. It is truly a harrowing, endless, and unrewarding experience, and I wouldn’t recommend it to anyone.