I downloaded Instagram for the first time a couple of months ago, wanting to see the feeds of my friends. I found pages filled with self-portraits: my friends in media res as eager, thoughtful people living active and seemingly happy lives. Taking a good, nonchalant selfie, I learned, is truly an art form.

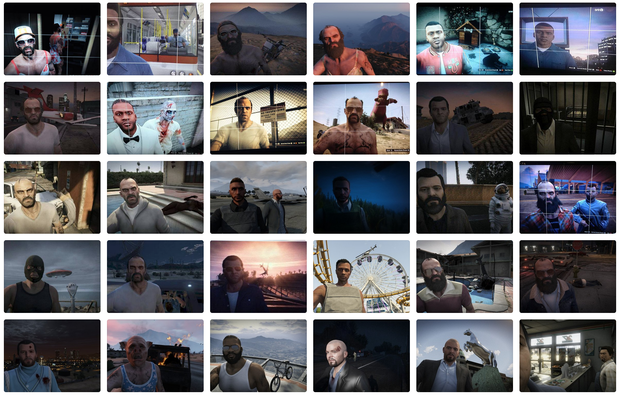

Taking a successful selfie in a game, like Wind Waker HD or Grand Theft Auto V, is also an art form, with added constraints. It’s not enough to just get a flattering angle on yourself as Link, Michael, Franklin or Trevor. The in-game selfie is really about the obscene action happening in the background. In GTAV, in particular, your selfie works best if the scene you capture makes sense given how we imagine these men. The pairing of your wide-eyed face with that action has to be believable. Scrolling through the thousands of selfies that players have taken across the Los Santos mini-verse (posted on the Rockstar Games Social Club site), I was struck by how dead-on players are in their authoring.

The in-game selfie is really about the obscene action happening in the background.

Nowhere am I Trevor, Franklin and Michael as perfectly as when I am taking a selfie as them. There are levels to this process of coming into our own as these three. They aren’t static, bound by lore books or intractable backstory. We create their lives as we play. We imagine the kind of lives they lead, and the limits around them. We hold a flexible idea in our minds of what they’d do on a normal weekday, where they’d go. And each time we take a photo of ourselves, we expand the meaning of what it is to be one of these men.

Players realize Trevor when they capture him scowling in front of a blowup doll, or before three police men shouting at him to stop taking a goddamn selfie and get down on the goddamn ground. His world—the Fear and Loathing in Los Santos world we imagine for him—is made and remade through each selfie. He angles his phone perfectly to catch the pink mountain sunset bathing his craggy face, a burning plane jettisoning across the sky. Or here, to immortalize his sinewy body in his skivvies, framed by a lightning storm, one of his eyes just slightly crossed. Or here, immovable in front of a gas station, swallowed in flower bursts of flame.

Where anything goes for Trevor, Franklin’s selfies are usually taken before his classic cars, on the deck of his art magazine-worthy home, sometimes in front of the strip club. He is poker-faced, inscrutable, possibly wondering at his own good luck. Selfies in which he is out of character and off-kilter (like Trevor) make less sense, because they don’t fit our idea of him. They are less funny as a result. Michael’s selfie expressions are most priceless of all: wide-eyed and confused, lips parted in a weird half-smile, lines under his eyes and striping his forehead, he stands in a tuxedo, with nowhere to go and no one to spend time with.

There is something sweet about these men submitting to the comically girlish impulse of a selfie. The idea of Trevor, Michael and Franklin hashtagging their pictures is even more comical: #ThereAreLevelstoThis #Lucky #Reckless #Balling #IWouldHateMeToo #YouOnlyLiveOnce.

Link’s selfies, on the other hand, own this sense of girlish playfulness. Set within Wind Waker’s cheery cosmos, Link comes across as a traveler, happening upon expansive washes of picturesque scenery. One can barely blame him for the need to document his presence therein: otherwise no one would believe that he’d seen such things at all. His are the selfies of the early-20s European vacation.

Yesterday, I nearly walked right into two ten year-old boys on the street. “Hello!” the tall one shouted, in my face. “I get that it’s a nice phone, but come on,” the other said. I got completely shamed by two children, and rightly so, because I was acting like a teenage girl. I was trying to take a picture of my new shoes for a friend.

Selfies tear off the veil: man or woman, young, old, or somewhere in-between, we’re all that teenage girl. Put on our best tempered smirks, crane our phones at an improbable angle. Hopefully, someone will tell us that we look like we are having fun. We reply, we are. We are, in fact, having fun. Hearts.

Only we would take pictures of ourselves as the world is collapsing.

Taking your own picture is a hilarious act fraught with existential dilemma. It is your proof to yourself that you are, wrapped up in a sly submission to your peers for validation. The picture whispers so much more than you’d like it to: I exist, here I am, see the most excellent environs I live in, affirm my taste. Some psychologists label the selfie as a foolproof tool for increasing your self-esteem; others term it the inevitable end of a visual culture that consumes itself endlessly.

Taking a selfie in a game dramatizes this process, and brings it front and slightly to the left, right there, perfect—center, making us see how absurd we are, for being us, for being, period. The selfies in GTAV tell us more about ourselves than the game’s whole universe of sardonic parody. When Franklin takes a selfie, masked, right before a home invasion, we laugh at the contrast of the banal act with the terror that he’s about to inflict.

This is the core of comedy—seeing our bumbling, hapless futility in relief against the great suffering and pain around us. Only we would take pictures of ourselves as the world is collapsing. Anything to shore against the abyss around. No one wants to die alone. But I look good today. Let me get a quick selfie. All will be well.