With The Wolf Among Us, Telltale takes a turn for the nihilistic

“We have lived too long,” proclaims a no-name in Lev Grossman’s The Magicians. “The great days are past.” It is even worse in Fabletown. Telltale’s new game The Wolf Among Us is heavily weighted, in a very different sense from its predecessor The Walking Dead, by bitter sentiment: not only have the golden days gone, but they never actually existed.

Adapted from Bill Willingham’s “Fables” comicbook, this decidedly noir enterprise focuses on fairy-tale has-beens displaced to New York. The story follows Bigby Wolf, a former huffer-puffer and grandma-eater who has supposedly reformed his ways, becoming the archetypal bachelor sheriff for the dreary denizens of Fabletown. The game plays out much like The Walking Dead, prompting dialogue choices and occasional player input as Bigby investigates Fabletown’s first serial murderer (after himself, of course).

To err, after all, is to be human.

Each of the residents of Fabletown has been rudely humanized. The game’s “grit-ification” of familiar fairytale characters (i.e. turning Mr. Toad from The Wind in the Willows into a foul-mouthed taxi-driver) is designed to show a bleak understanding of human nature. To err, after all, is to be human. Centuries removed from pedigree and enchantment, we now see the fabled Woodsman reduced to a drunken bar-brawler, a princess selling herself on the street corner, the jolly Mr. Toad wallowing in the ghetto. Snow White plays the unhappy public servant. Bigby Wolf, long past his days of being “big” and “bad,” is struggling to prove himself in a community who hates him. The fairy tale animals have become tired people who have outlived their stories, for better or for worse. As in Sondheim’s Into the Woods, every happily-ever-after has its fallout.

These “happily ever afters” were nothing more than stories even for the characters in them.

The German word Sehnsucht describes an intense longing for a world or state of mind beyond this one; the Portuguese call it Saudade. Each character longs for the good old storybook days. Dig deep enough and you’ll find the storybook stained with everything from petty burglary to incest; these “happily ever afters” were nothing more than stories even for the characters in them. Simple abstracts are easier to idealize. Every character, from Beauty and the Beast to Bigby Wolf, is in the grip of Sehnsucht and seems to long for a simpler world.

All this yearning for the past is echoed in the game’s deeply, almost painfully nostalgic aesthetically. The game’s color palate brims with vivid 80s neon, garish and abrupt, while the soundtrack is awash with warm synth chords. Even the writing bites of old-school dime shop noir thrillers. It’s nothing we haven’t seen elsewhere; in fact, there doesn’t seem to be a single thing in The Wolf Among Us that doesn’t ring familiar, tired and edge-worn from overuse. But that is perhaps Telltale’s (and Willingham’s) intent: the tired tropes and trappings of our impossible ideals are condemned to burn themselves out in unspectacular and unflattering ways.

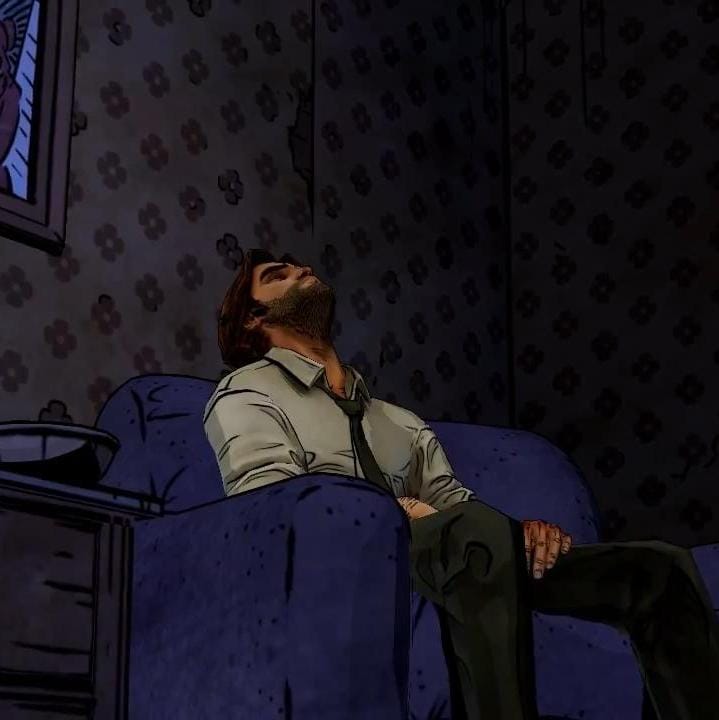

Yet Bigby Wolf steals the spotlight as the seemingly irredeemable anti-hero craving redemption. In a community fixated on the past, all he’d like is the “clean slate” he was promised: to forget and be forgotten if not forgiven. It is a cruel irony that Fabletown’s biggest, baddest monster happens to be the one keeping the peace. He presents himself with a low growl and sidelong look, far from The Walking Dead’s idealist ex-convict Lee Everett. In The Walking Dead, Lee found purpose in either preserving or tempering Clementine’s naiveté. Bigby Wolf has no Clementine, no deeper sense of purpose other than to survive in a world full of frightening enemies and half-allies. Given Fabletown’s mistrust and the trajectory of such future episode titles as “In Sheep’s Clothing” and “Cry Wolf,” The Wolf Among Us seems to suggest that his “clean slate” will be hard-won, if not impossible.