WORLDS COLLIDE: On Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 and Style in skateboarding

2000 was a weird time to be a teenager. We had the millennium bug and the Matrix promising false futures, we had Napster, arguably the most liberating tool in the history of music, and we used it mainly to download nu-metal. Kurt Cobain had died six years ago and we were hanging on to grunge by a tattered thread without having ever experienced it firsthand; the internet was dial-up and we asked Jeeves; flame-sleeved shirts were the peak of cool. Though I’m biased, I find it difficult to imagine a more hapless, directionless set of youths. It could be a combination of the factors above, or simply because we were teenagers, but when Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 was released it felt like an answer, a solution, a raison d’etre.

Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 was a fully formed package of music, video and style, all with a sprinkling of commodified anarchy. A whole world of possibilities were presented: from the intro video alone the quick flashes of Kareem Campbell, Eric Koston and Andrew Reynolds skating real-life streets, ledges, benches and stairs, it was like unlocking the doors of perception irreversibly. Previously game environments had been either cinematic or fantastical, but here humble sidewalks and pavements were transformed into platforms of potential. The game also inserted Rage Against the Machine, Bad Religion and Public Enemy (via Anthrax) into unsuspecting homes across the world, like, I don’t know, a guerilla radio.

Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater was released a year earlier to largely positive reviews. Originally conceived as a downhill racing game, it combined elements of racing, platforming and arcade sports games. But it also felt more fluid than the other skating games of the time, and more open than the immensely fun but inherently limited Cool Boarders snowboarding series.

Humble pavements transformed into platforms of potential

The additions to Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 (2000) were not exactly groundbreaking, but they were many: manuals (wheelies), two player free skate, create-a-skater (male and female), create-a-park, larger levels, all of which extended the longevity of the game exponentially. The levels were now designed with manuals in mind; the skater could link tricks without having to grind on the edge of an obstacle, and as a result the levels were larger and more expansive. This allowed more freedom and more potential for exploration, which was fundamental to the experience. Also, after playing the finished Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, designers at Neversoft had time to reflect on what worked and what didn’t in the levels. While the career mode focused primarily on the frenetic high scoring and extreme combos, the larger, fine-tuned levels were best appreciated in Free Skate mode.

There, beyond the two-minute time limit, away from the structure of the scoring system and objectives, there were no aims other than to skate, freely. While many used this mode to improve their combos, to practice special moves and to treat each level as a training arena for their career progression, others would seek out secret spots or unskated lines. There was a thrill in controlling the prodigious avatar into a first-time 100,000 point combo, akin to defeating a boss or beating a record lap time, but there was a thrill unique in the understated simple trick. The kick of landing a 360 over a gap or bluntsliding a ledge on your own terms was exhilarating because it was your choice; you felt a sense of achievement and independence. While the career mode encouraged you to skate in a certain way in order to complete objectives, away from this, the game was open for personal expression. Free Skate offered no tangible reward for the endless laps, the never-before-done tricks, but back when games were limited by technology and Grand Theft Auto style free-roaming 3D cities were a distant vision, this simple freedom was at a premium.

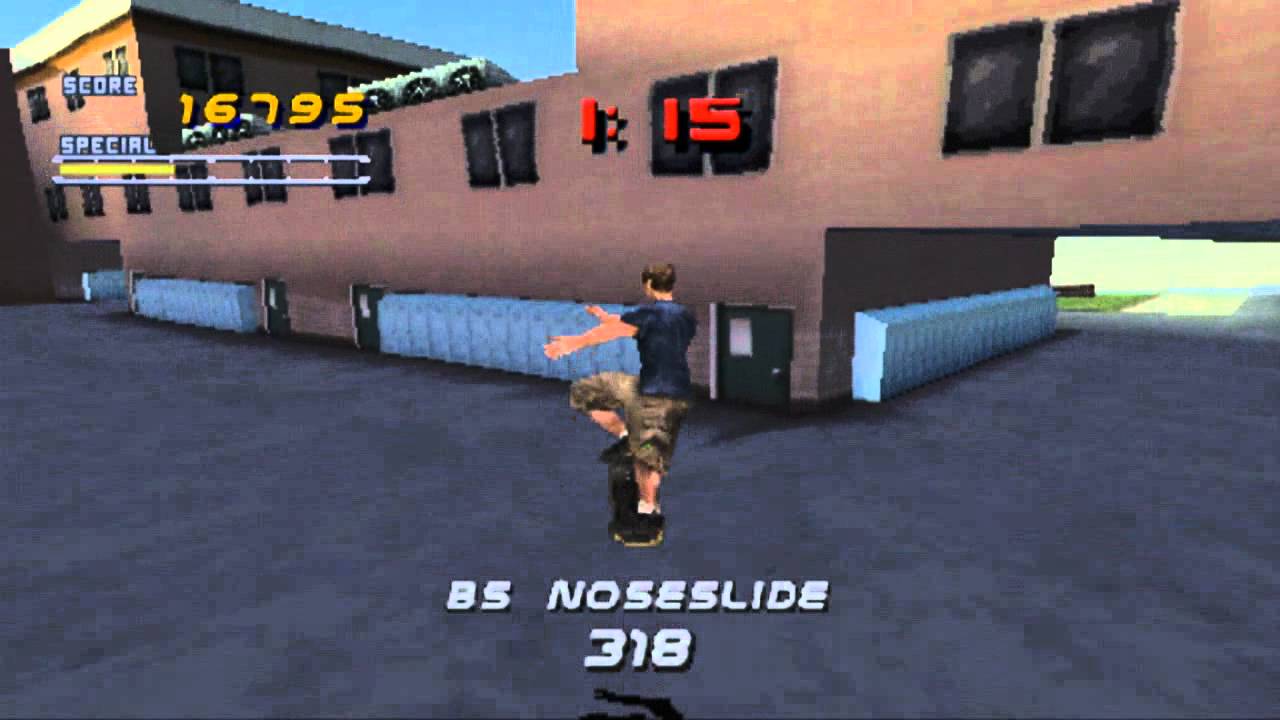

The School II level was where I learned my trade. While there was a certain irony in the industry and effort I put into my extracurricular activities here in comparison to my real life studies, at no point did the game feel more perfect than while skating the School II. Adapted from the School level from Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater, it illustrated the evolution between the two games; The School version 1.0 had huge pools and vert ramps snaking through the level, and it felt like a skatepark masquerading as an educational facility (though possibly one focused on the pursuit of excellence in extreme sports). The School II, on the other hand, felt real. Of course there were still the conveniently placed ramps and the forever frictionless ledges, but combined with the picnic benches, bins and school bells it felt more in line with reality. The School II had a few real life iconic skatespots integrated into the level, none more iconic than “The Leap of Faith,” a notorious ankle-breaking two-story drop as skated by Jamie Thomas in 1997. To begin the level you could either hop down the drop or grind the 40 ft handrail beside it, both with total ease.

The School II level exemplified Tony Hawk’s combination of the prosaic backdrop of life with the superhuman abilities of the skater in an almost magical realist take on skateboarding. You could pop shoulder-high ollies, grind eternally and recover immediately from the most nauseating slams. The game was a caricature of the escapism that skateboarding provided, with the perfectly crafted environments uninhibited by the barriers of friction, risk, pain and ability. For me, a not-so-gifted beginner skater in the rural middle of England, the eternally sunny, smooth levels were just as exotic as the calibre of skating.

The game presented skateboarding as a grand Western—a lone skater travelling the globe in his quest for points, winning competitions and cash prizes communicating solely through the medium of skating (and occasional grunts of pain). There were no other people in the game other than the anonymous judging panel on competition levels, fellow silent skaters and the drivers of the cars that circled certain levels endlessly. Despite not being a “living, breathing” world by today’s standards, there were endless trick combinations and possibilities, enough variation among the levels that you never felt alone. Or at least, if you did, the lack of distraction was welcome.

Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 presented skateboarding as a grand Western

This streamlined vision of skateboarding bears little resemblance to the real-life skate world. Skateboarding is rarely a solitary pursuit: at the very least, all recorded skateboarding requires a filmer plus the skater. The game also revolved around the competition circuit, which in reality is fairly insignificant. Skateboarding exists proudly without any overarching league, rankings or stats. The focus on doing complicated trick combinations in order to score high is largely at odds with the aesthetics that most skaters value. The ethos generally being that a simple trick done well is better than a harder trick being done badly.

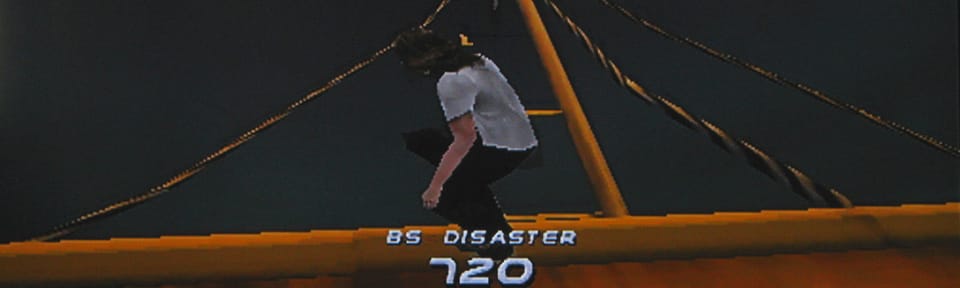

Recognizing this, Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 implemented the Sloppy and Perfect trick classifications. Essentially, if you under- or over-rotated a trick and your skater landed not facing entirely forward, the game would judge your trick SLOPPY in red letters and subtract 500 points from the trick score; conversely, land perfectly forward and your trick would be commended as PERFECT and net 500 bonus points. This acknowledgment of style over substance was slight, but significant. The gangly animation for a SLOPPY landing, in addition to the loss of speed afterward, was jarring to the game’s sense of movement. Despite largely being judged on a completely different framework, this was a subtle reminder from the game that style counts.

Style and simplicity in skateboarding are sticking points. These principles largely hold firm throughout the skateboarding community, which is why various insiders will dismiss highly technical tricks with the koan, “I’d rather watch Gino push.” First uttered deep in online forums, this saying celebrates the nonchalant propulsion of 90’s skate legend Gino Iannucci. Now a joke in itself, it still offers an insight into a mindset that might seem paradoxical when viewed solely through the onscreen interface of the Tony Hawk’s score counter. Skaters are not luddites, but there will always be an underlying ethos of purity, of style and of aesthetics that makes a Backside Tailslide more appealing than a Nollie Inward Heel Five-0 Shove-it.

Another common dismissal of modern skateboarding, often when the perpetrator has a consistent, clinical approach to tricks, is that he or she “looks like a videogame,” implying that there is little self-expression, freedom or nuance in the performance—just a soulless, robotic act. Boring even. The source of this disparagement is no doubt the rigidity of our Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater avatar. There’s some validity to it: It is true that the tricks are performed with mechanical efficiency and even in slams their body bounces and the blood spits in uniformity. But that’s also the entire point of our skater: to be the blank model through which we experience this manufactured world, to be the crash test dummy for our outlandish attempts and the heroic champion in our successful stunts.

One of the things that added to the longevity of Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2 was the simplicity: it was more a facilitation of freedom rather than a simulation. There was no attempt to be a virtual incarnation of the world entire; it was a cartoon more than an oil painting. A starting point, the art of skateboarding in isolation, the lone skater plying his trade across the globe, to what ends? There was no storyline and in glorious hindsight this looks much more like a blessing than an omission. Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 4 was the first in the series to fully take advantage of the PlayStation 2, building a sprawling career mode whereby you would go to a level and run a series of farcical errands (escaped animals, distracting guards, grinding various people/places/objects) all from atop a skateboard. Tony Hawk’s Underground was the first to have a story mode as such, charting the rivalry of one small-town skater and another, which culminated in said rival burning down said small town. Eventually Bam Margera shared the cover art with Tony Hawk well, and the less said about this, the better.

It’s true that the franchise could not have survived resting on the laurels of Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater 2, and, while the ambition of Pro Skater 4 and its successors were admirable, they missed the point. Skateboarding is inherently a subversive act, using architectural forms in another way than they were intended. Using creativity and physicality to harness cityscapes to a different end, there was no need to shoehorn in anarchy in graffiti minigames, dangerous driving, minor acts of terrorism, jackassing, even BMXing. The anarchy is in the energy and spirit of skateboarding rather than the specifics. Though the Tony Hawk’s franchise is no longer the relevant touchpoint for teenagers today, there’s a whole generation who owe a lot to Neversoft, the School 2 and the subtle anarchy of Free Skate mode.