Yasmin Elayat is a self-proclaimed ‘hybrid’—she’s a new-media documentarian, a creative technologist, a collaborative storyteller, and a spatial designer. She co-created #18DaysinEgypt, a collaborative documentary centered on the Egyptian revolution; co-directed an interactive documentary set within the New York City subway system, Blackout, and Zero Days, a VR film about cyber warfare that won an Emmy for Original Approach in Documentary.

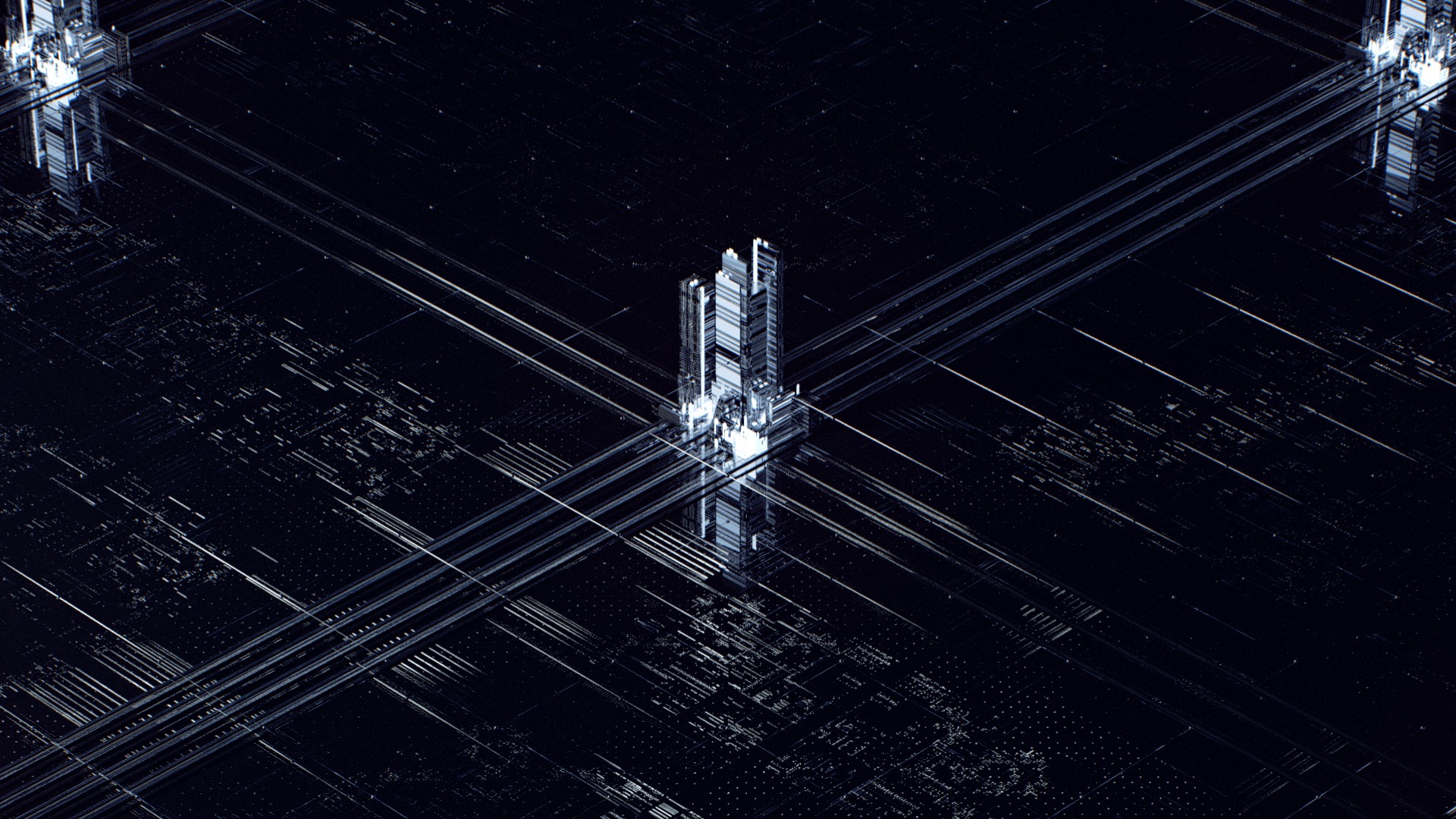

Along with James George and Alexander Porter, Yasmin is also the Co-Founder of Scatter, a New York-based entertainment studio that creates tools and collaborates with artists to ‘volumetric filmmaking:’ storytelling through immersive technologies. Scatter’s Depthkit allows its users to create accessible storytelling experiences through 3D capture.

Here, Yasmin tells us about how working in a museum space led her to spatial and volumetric filmmaking, demystifying the role of creative technologist, and what it’s like to run a tech company fueled by creativity—one that continually redefines itself alongside its community.

Listen to our conversation with Yasmin on the Killscreen Podcast.

BETWEEN ART AND TECHNOLOGY

Can you talk about when you started your path into the field of creative technology; when that first emerged for you as a creative impulse?

Now that I look back and reflect, I realize it’s always been there. I grew up in Silicon Valley, and my dad had a startup. I was one of those privileged young children who had a personal computer. I remember teaching myself to program at a young age. I was 10 or 11 when I started programming, but I began to program to basically build websites just to show off my drawings and my poetry. I wasn’t trying to be an engineer, actually. You saw it as a means to an end.

Even though I studied computer science and worked as a software engineer, I gravitated towards art school and went to ITP at NYU. I thought, Okay, there’s definitely a way to merge the left and right side of the brain here. There’s something about knowing the possibilities of technology. I find it liberating that if something doesn’t exist in the world, you can always build it. It’s exciting for me, but I was never excited to be an engineer to solve technical problems.

I was always excited about stories that I wanted to pursue—but because of how the creative process in my brain works, it was still not traditional storytelling. I like telling stories in different ways or new ways that haven’t been told before. It’s always been there, but it became more solidified after grad school when I was in art school and in New York. New York is a place where hybrids, like me, could find a place because you can be an artist and a technologist.

STORYTELLING THROUGH SPACE

Was there something specific from working with the physical space that informed your work later on?

There was something about the Holocaust Museum. I found that museum space and cultural space actually the most experimental—there was the element of being relevant to audiences, or engaging several generations. It was a new building—beautiful architecture, innovative. They wanted to do everything connected, so we built an entire audio guide to talk about every interactive piece in the museum.

Part of it was how do you work with such heavy subject matter? Especially sad stories, very hard, very violent things that—to hear and learn about and translate it into something material, and being sensitive and respectful to the material. Also, trying to tread this balance and doing it in a beautiful and poetic and mature, sophisticated way. That was a significant learning experience. It was also a huge technical feat.

I felt like the leader of a team—I understood that I could play these dual roles. It felt natural and fluid to speak to the engineers, but I also learned how to think about spatial narrative. It’s one of the most beautiful marriages of literally designing from the ground up with the architect. Everything was seamless. Everything worked together, from what we designed to how it was eventually laid out.

How did you first make your way into virtual reality? How did those encounters open the door to your work at Scatter?

There are two critical bits to mention that led me to Scatter and startup into an XR space. After Potion, it was the first time I quit my job and started my own project, my own film, interactive film project supported by the Tribeca New Media Fund and Sundance Frontier at the time. The inaugural class of both of these funds and labs.

This project, #18DaysinEgypt, was the first time I was working independently. This was at the time when we didn’t have a space for where these projects fit anywhere—I was thinking about how do you tell stories using emerging technology? Specifically, I was always interested in documentaries.

The second important beat was that I also started a company with #18DaysinEgypt as its foundation. The project was an outsourced collaborative documentary about the Egyptian Revolution, where anyone who’s there on the ground can tell their story. It was like an ongoing story to capture the moment and keep this grassroots storytelling, having the people in their own history or a country own their own histories.

We realized that platform that we built for that project from the ground up over a whole year became a company, became a startup. My first company was also a company about storytelling. Those two things were pivotal.

I worked as an artist, and then I came back to New York, where I met James. We were both computer scientists, artists with strange films that didn’t fit in a box—but they were both these documentaries relevant to ourselves and the communities we were part of. Before joining forces with James and Alexander, I’d always embraced whatever was emerging technology, whether it was wearable tech or web.

I went to ITP when iPhone-based games were the new technology. What’s really cool for me about XR was it’s the first time that I saw a potential ecosystem. When I finally did start working with James and Alexander, how the Scatter started wasn’t straightforward. There’s something about seeing your future as an entrepreneur happening, and seeing what they’re doing with that kid at the time was RGB toolkits. It was 2016, they were moving into productizing it into a company, and that’s when I was also a free agent and looking for my next thing.

BRIDGING TOOLS WITH CONCEPT

Throughout your career, the content you’ve worked on informed the tools and technologies you had to create or implement. What does that look like for Scatter now, especially since you’re in touch with both the creative and technological sides?

We’re an artist-led company, and so we definitely lead with the creative. This is literally how we operate. We believe that art drives innovation. For all of us as founders, that’s what drives us. We actually all come from that kind of ethos before we met each other, the fact that starting a company, that’s how it’s led.

Art drives innovation. Even DepthKit was created to serve as a creative project. It was started as an expression between James and Alexander back in 2011, actually. This idea of the beginning and the seeds of volumetric filmmaking started the pursuit of creating this documentary about the creative coding community. It is still true today of Scatter.

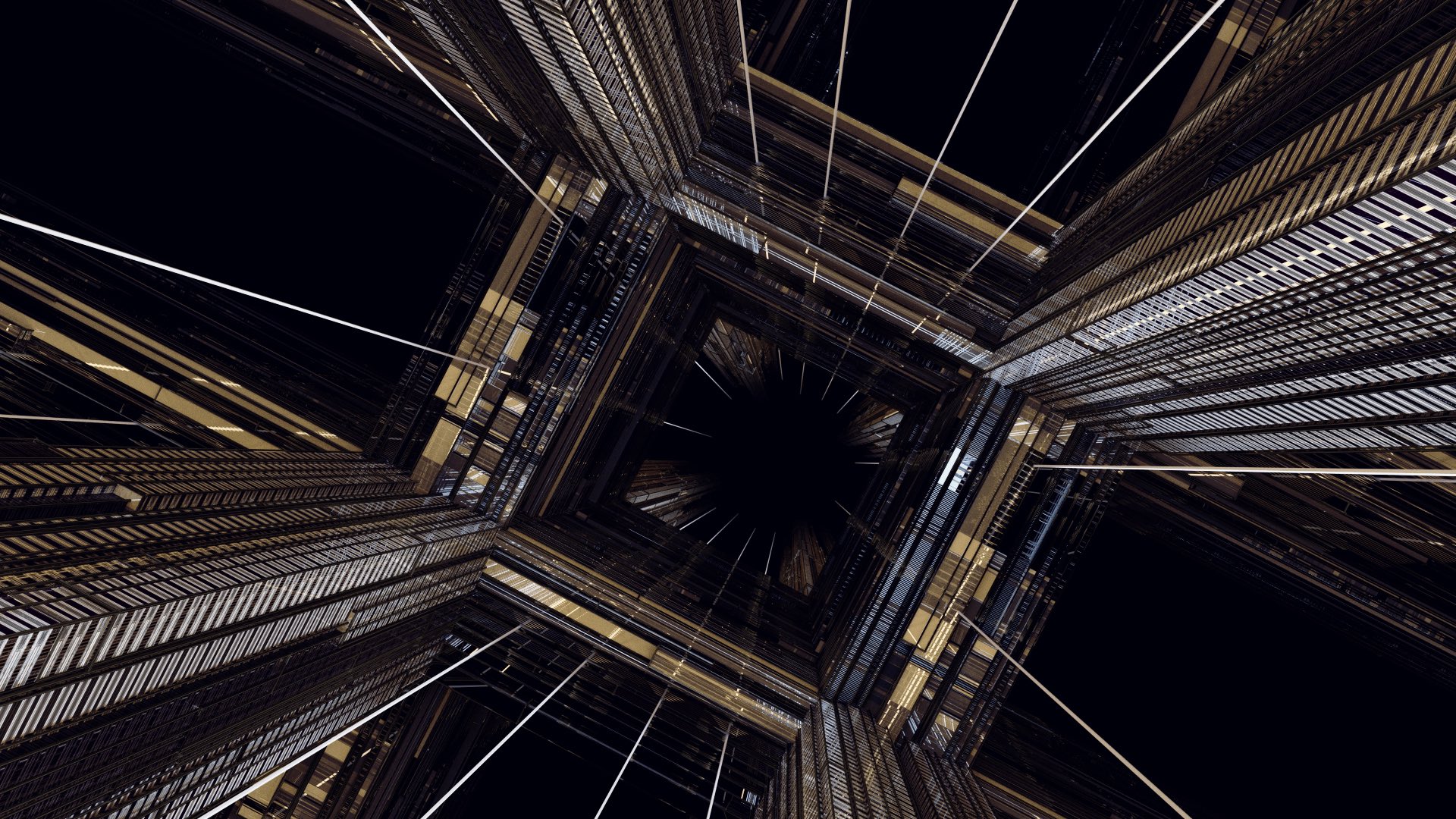

I really believe this idea of volumetric filmmaking, which is the term we’ve coined, is more significant than just a tool. It’s a new way of being; it’s a new way of telling stories. It’s a new way of a creative process that’s beyond just volumetric capture. It’s a whole workflow. It’s a whole way of creating, and it’s also not built just for arts, but for filmmakers and other types of formats and publishing formats.

One primary mission is how to define volumetric filmmaking and see that anyone interested in this space is our collaborator. We don’t use the word customers. We don’t see customers as customers. We see them as our community. We call it our community because it’s the volumetric filmmaking community helping build something that doesn’t exist.

Everyone is involved in building it and defining it. Part of that’s what we lead with. Knowing that in service of determining what volumetric filmmaking can be, then we work backwards. That’s what brings us home, is the way to say it, which is our productions, or you can consider them like the R&D arm of what’s next.

Then because we’re ‘dogfooding,’ we’re literally building what we know we need and what the future is and defining the future through their productions. Our tool then makes sense because we know we need this. Productions are also testing it in the process of productions, and we’re collaborating with the community. I would say the way we’re building tools is not like a regular tech company because it’s tools we as artists want and need. It’s actually quite poetic. It’s the dream, right? To build a company as an artist where you can do both, run a business, and work on projects you really believe in. It’s not easy and simple.

I was one of two women in my class or a few women and always the only female engineer. There’s something that I feel has a responsibility and where this is coming from. I think what we’re doing is intervening at Scatter. It’s about the diversity of storytellers, it’s about accessibility, making sure that both ends the stories that are being told are diverse and representative, and that the creators themselves are too.

If you’ve ever been to any of our events, I hope you can see that this is reflected. Also, in the kinds of projects that are being published, it really is true. It’s important to say that because there is this responsibility, which is we’re doing this because it’s a way to intervene and the future of technology and the future of what this space in volumetric filmmaking would be. I believe there’s an element of that. Whether or not it’s explicitly said, there’s definitely something that’s thriving us as a team that comes from that place.

COLLABORATING WITH COMMUNITY

What do you find to be the ideal use case for Scatter as a tool? What types of creators are attracted to it, and what do you find them using it for?

Volumetric filmmaking is a way to capture the real world, but it’s also a way to translate it and play with an aesthetic spectrum.

That’s something very important about Scatter. If you look at other reality capture tools, they literally capture tools, or they’re volumetric capture holograms. For us, it’s not that. It’s not just about holograms. It’s about creative expression. That’s why we always support different VFX workflows like Expert. We work with VFX tools that exist, 3D tools, or within Unity, We work with VFX Scrap and the Shader Graph.

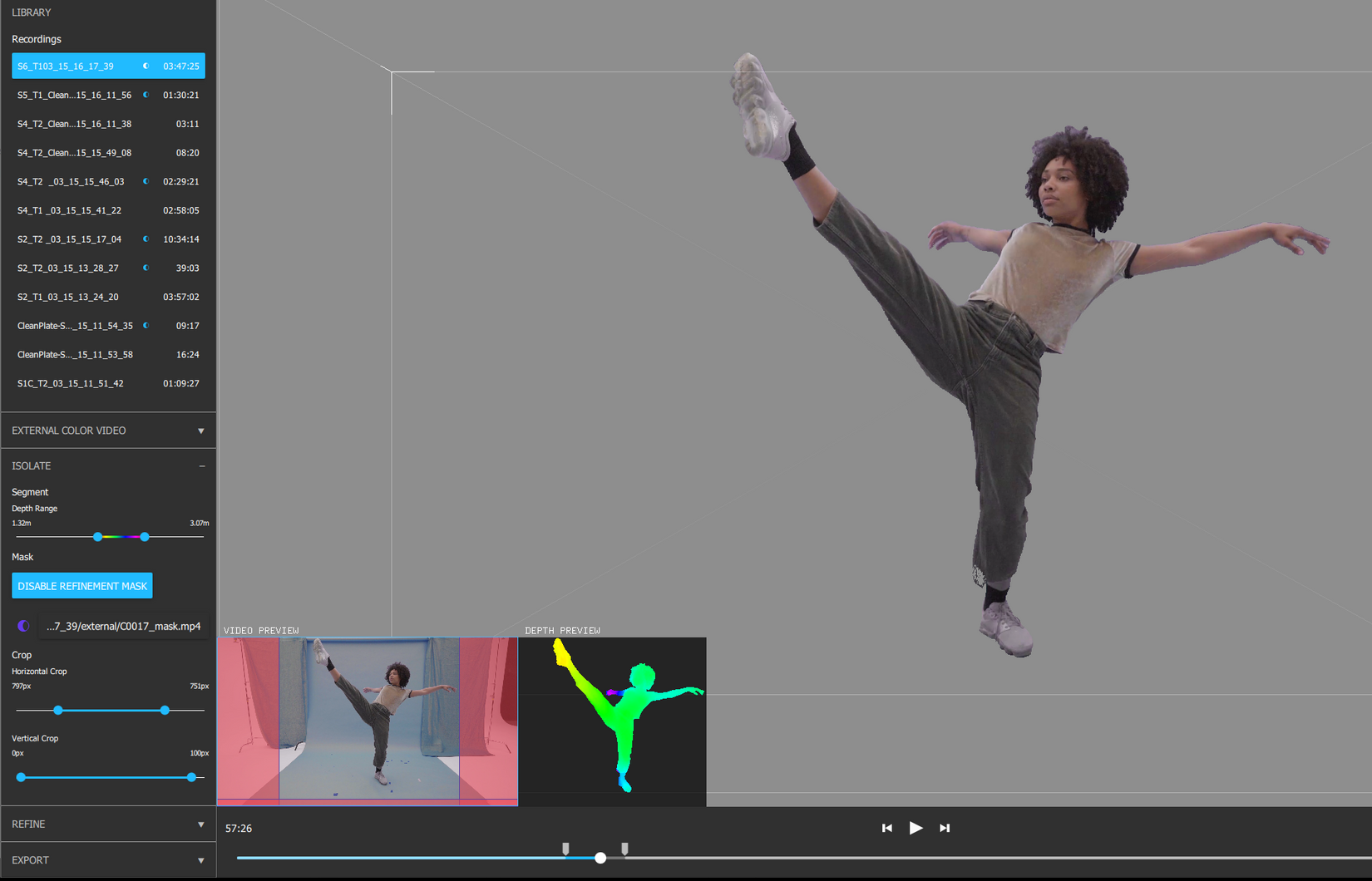

The documentary filmmaker Alex Gibney, who made Zero Days, wanted to use DepthKit as a VFX tool, too, in a way that felt native to the language of code or Eminem used in the Rap God music video. Also, in the XR space, it is an accessible solution. If you can get started with a machine and a sensor that’s a few hundred dollars versus a lot of our indirect and direct competitors, it’s more complicated. There’s lots of hardware. It’s much more expensive, and they’re not portable or mobile.

This idea of accessibility, mobility, and portability is attractive to many independent creators, of course. We have a lot of independent creators in the XR space that have used DepthKit. DepthKit has the most published volumetric films in this space compared to anyone. Our most direct competitor has had half of what we’ve published. Not us. Our community is true to what we believe in around diversity and things like that.

One of my favorite projects is in Brownsville. It’s a neighborhood in Brooklyn, and these young Black kids wanted to recreate; they rebuilt their neighborhood, they made a video game out of it. They shot hundreds of people in their community using DepthKit to collect their stories. It was like, “We want to own the narrative of Brownsville. Brownsville is our community. Brownsville is people that care about each other. Look at all these beautiful stories.” The human side of it versus what you hear in the news about Brownsville. That’s beautiful.

DepthKits are used in the Middle East and in Africa. It’s hard to get access to the hardware and tools but the fact that filmmakers are using it to make projects, to publish VR projects, or make XR space.

It’s meant to be accessible and something that any creator can see themselves using, and we’re trying to make it easier as we go over through the years. It’s still hard and expensive to make XR that works. Still, it should speak to people beyond the XR spaces—any storyteller could see themselves using DepthKit and working in the volumetric filmmaking space because we really do believe it’s the future.

It’s like there’s going to be this collision—already, it’s happening with virtual production. There’s a collision between these game engine tools, and the ability that they provide, as well as the craft and sensibilities of making that is—you can never lose. It’s the key. It’s what we lead with.

That’s why we call it volumetric filmmaking versus holograms or volumetric capture because we really do believe in that. It is a creative practice, and hopefully, the people it resonates with are using our tool and making things work with DepthKit.

Do you have a sense of what comes next in terms of distribution tools, especially since not everyone has access to a VR headset?

It is a big problem. It’s a whole ecosystem; it’s not just the distributions. It’s also which parties get funding, where can you get funding for this work, is there enough profit on the end—on the app store, for example? On the tool side specifically, that’s why we make sure that we support different publishing formats.

That’s why the beauty of DepthKit is you can shoot with DepthKit, and then you can use the same asset to make a film. That same, in the format that we shot back then, is actually the asset we used in Zero Days VR and built a whole virtual world and around the same shoot. It could be working in both formats. That’s why we support different types of ‘expert’ formats because we understand that it’s a problem. The web is what we are trying to move towards because it’s the most accessible for now until headsets get cheaper, or there’s a larger number of people buying them. AR is a whole other space. I would say that that may be one of the ways to reach audiences, but it’s each technology, why you pushed me means something different, and you’re trying to say something different.

Not the same story will translate the right to different distribution models. It’s still something we are cognizant of, and we’re trying to make sure that we’re supporting the whole space versus just the XR space. It’s like, Let’s support all kinds of creators, even if XR is still nascent right now. It’s still as a market ecosystem you can support all the other types of ways of creating.

Then on the production side, it’s a struggle. Right now, even more, so where we have a project focused on the racial justice movements—it’s about the 400 years of American citizens with racial injustice, and it’s a magical realist time travel experience. It’s about how it just evolves but doesn’t really change. It’s magical-realist, Afro-futurist, and very pertinent right now.

The reason I’m bringing it up from a production standpoint now in this climate, the traditional way we would have approached distribution doesn’t totally make sense anymore. Like the way film festivals are adapting. We have to rethink and be a little more creative. Because we’re Scatter, we are always like, Oh, if something doesn’t exist. What is the thing that we need here?

We’re at that moment where I don’t know how to answer yet. At Scatter, we’re always in the headspace of, What is missing that will help us build and enable a project like this to connect, to succeed, and to thrive?

THE BOUNDARY OF CINEMA AND INTERACTIVITY

Zero Days existed as both a film and a VR interactive experience. Do you find that creators come into it with the expectation that they’re to make a film first, or an interactive experience first? Is that something they figure out along the way as they’re in the process of building their storytelling vision?

Most people come with their own vision. Either they’re working on a film, and there are a few feature films. What they are, they are documentaries or not all documentaries that are or someone is specifically coming in to do this music video or someone is explicitly working in virtual reality. Sometimes people will switch—they will play with VR and an AR component or a mixed reality.

It’s only us [at Scatter] who’s been dipping our toes in both with projects. Most people either don’t realize it, or maybe they don’t realize that they could work this way or it’s already costly and hard to do one or the other.

It could be something that exists in the same world and the same visual space and design metaphors. They’re always building worlds. There’s something there, but now no one has really come out that I can say except us that has done that.

The model of showing what you can do through creative practice makes an awful lot of sense. Hopefully, larger companies continue to invest in content to showcase what the technology can do, rather than just saying, Oh, yes, creators will figure it out, and they’ll figure out a way to monetize it.

We definitely believe it. You could be a tech company, or you can be like us, which is, we’re not a traditional tech company. We’re not driven by the demands of just technology for technology’s sake. You build tools differently in that way, and you make choices differently. Also, because we’re in this space and making work, too, these are our peers. They’re not our customers. We have the same needs and struggles as our community. It totally changes how you build and what you’re building it for.

It’s also hard. Obviously, that’s why there’s not a lot of companies that are like that. That’s how many Oculus and other companies start that way with this heavy investment and then realize it actually takes a while, so you see the return. It’s definitely not the simplest way to work. It’s true for us. One thing you’ll see is, we’re true to our core and our ethos and our values. That’s something that I’m proud of about us as a team at Scatter.