The Year in ADHD

Friedrich Nietzsche once wrote of 19th-century society, “That everyone may learn to read, in the long run corrupts not only writing but also thinking.” His observation couldn’t have been more far-reaching. The internet has been changing the way people think, slicing up and dishing out snippets of idle chatter, ever since the days of the Bulletin Board Service. Since then, our dependence on the information mothership has grown. At times, I feel that my brain is becoming rewired so that it no longer accommodates the media of old.

To be more specific: This is the first year that playing videogames has made me feel like I have ADHD. Nesting in front of the TV for a 40- to 80-hour run through The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim or The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword sounds more like exile than an excursion. The thing is, I no longer want to escape. I want to be fed a steady stream of data through a Wi-Fi antenna that is positioned as close to my brain as possible-which often turns out to be on my phone, a download service, or linked to in a blog. The stream has even infiltrated the way I play.

What struck me about the games I liked most this year, even more than the fact that they were all short, instantly gratifying experiences, is that half of them—2012 IGF Pirate Kart, Minotaur Rescue, and The Dishwasher: Vampire Smile—wouldn’t fit on Game of the Year lists from a few years ago. They would be relegated into their own category of top downloadable or mobile-phone games, as if their ephemeral nature made them a lesser creature. To be honest, I was hesitant to put Pirate Kart on my High Scores list at all. It lies very far outside the norms of what even I think a game is. For one, it has to be downloaded from a torrent site (even though it is perfectly legal). The file, which I keep on a zip drive on a keychain, collects more than 300 by-and-large terrible outsider games that are more of a curated protest stunt against indie domestication than thoughtful executions of game design. Most of them were made at the last minute (read: 48 hours) after a group of indie game makers rallied behind a tweet by Bentosmile, which simply asked, “Why is there no Pirate Kart for [Independent Games Festival]?”

I would say videogames are also becoming a web-like experience: one in which the player can get carried away by the flow of information.

The IGF Pirate Kart is hilarious and outrageously bizarre (see: You Have to Knock the Penis), but besides that, the reason I chose it as my No. 1 game is that playing it comes closest to my mental state when I am perfectly attuned to the internet: those fleeting moments when the feeds I follow are giving me exactly what I want, when I want it, without my even knowing I want it. William Gibson’s description of Zion dub, the autonomous, computer-generated music found in Neuromancer, sums up the experience. He calls it “a sensuous mosaic cooked from vast libraries of digitalized pop.” Pirate Kart is one of the few games that makes good on the prospect. I can effortlessly ride its stream—a list of games that can be sorted by author or chosen at random—to content that will consistently entertain and challenge me. The quick pace of navigation and the joy of discovery are as important as the games themselves. In a column for Pitchfork, Tom Ewing compared the social media stream to videogames, saying that it is “perhaps … best understood as the finest version yet of the web as a game-like experience.” I would say videogames are also becoming a web-like experience: one in which the player can get carried away by the flow of information.

Though Pirate Kart is fixed in place, located on a file downloaded to your hard drive, it nonetheless flows. Its libraries are vast enough, and its content suited well enough to my tastes, that it feels like a highly productive session on the ‘net—only minus the Like button. Pirate Kart is inclined to feel like surfing, since it and other compilations, like the quick-and-dirty Ludum Dare contests and previous Pirate Karts on Glorious Trainwrecks, are as much a conversation among a nihilistic online community as they are collections of irreverent mini-games. This gives them a nowness that is lacking in games that spend years in a development cycle. It is a stark contrast to the landscape of Skyrim, which feels like it occurs eons ago in Tolkien’s Middle-earth. The Pirate Kart doesn’t have a setting at all. It has a black background emblazoned with a skull-and-crossbones, and it has a very long list of links—some launching games that are so rough around the edges that you have to restart your computer to get them to go away, and others linking you to sites with a text adventure about a dinner date gone horribly wrong, where your lesbian lover is trying to cook you.

While Pirate Kart is easily dismissed as fringe—a group of “no-name” hobbyists plotting raids on normal people from an uncharted island of the internet—even Mario, gaming’s most well-recognized mascot, has been influenced by the structure of the ‘net. Where once we would find a set of lava levels, desert levels, ice levels, and so on, Super Mario 3D Land has shed any semblance of a world, instead taking place within the logic of the stream. There is no longer a bird’s-eye view of a world map. The level-select screen is arranged in a straight line that you scroll back and forth. The levels before and after have little in common with the one you are currently playing—except that you jump through them. It is like reading the front page of Reddit, where headlines are arranged arbitrarily by votes; or a Twitter feed; or playing Pirate Kart. The levels are spontaneous and extremely brief, a combination that ensures I will stay glued to my 3DS until its batteries run out, no matter how often it warns me that I may be doing damage to my eyes—even though I am left afterwards with only a vague recollection of what I have been doing.

This is the first year that playing videogames has made me feel like I have ADHD.

Mario isn’t the only mascot mixing things up. Kirby too is trying to keep up with the rate a Facebook wall is spammed with scores. The hyperactive romp through Kirby Mass Attack takes the idea into overdrive. Not only does each level go in a new direction, but the direction is shaken up several times over its course. In my review, I said it was a reaction to “the app-game generation”; that it “seems afraid that you will get bored” with Kirby’s traditionally laid-back pace. Yet the trend goes beyond cuddly Nintendo characters. Cult director Goichi Suda’s vision of hell, Shadows of the Damned, never does the same thing twice. Sure, headshotting a demonic road crew is the staple—but Suda takes the idea and runs with it, filtering it through so many two- or three-minute variations that it feels like listening to a well-curated playlist of punk-rock songs. On the other side of purgatory, El Shaddai: Ascension of the Metatron‘s divine aesthetics do the shapeshifting. Each level has its own distinct, jaw-dropping visual style, relying on abrupt shifts in art direction to keep you tuned in to the rhythmic combat.

Other games incorporate the stream directly. Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP, seemingly set in a wormhole between Hyrule and Mesopotamia, allows you to tweet stanzas of stoner-speak as you come across it during the game. Battlefield 3 opts for a browser-based interface, so you can have a dude-bro social experience in between rounds of shooting down helicopters, reading a stream that keeps you up-to-date with the goings-on in friends’ games. Dark Souls lets you to scrawl out notes of despair on stone, so that you can tell strangers how much you hate yourself. When they find your message in their own game, they have the option to vote it up.

It’s as if the stream—this never-ending current of information, which lets us feel that we are a part of something else, even when we are doing something presently, and that reminds us that the world is moving with incremental ticks—is now needed to distract us from games, the things that distract us from life.

The reason why none of this bothers me—that the stream is corrupting thought, that I need to be distracted from my own distractions, and that one day all big-budget games may be a small version of Facebook—is, unfortunately, a crass one: I like it. I like when images flit before my eyes and quickly fade away. I like the rush of nervous energy that comes from short bursts of wildly varied content, because I don’t have the patience to sit through 15 hours to get to the good part. I like when a game acknowledges that it is a part of a greater world around it, occasionally commenting on it, even having me interact with it, instead of creating a massive, digital world for me to lose myself in. I like gaming in the stream. So what if I have ADHD.

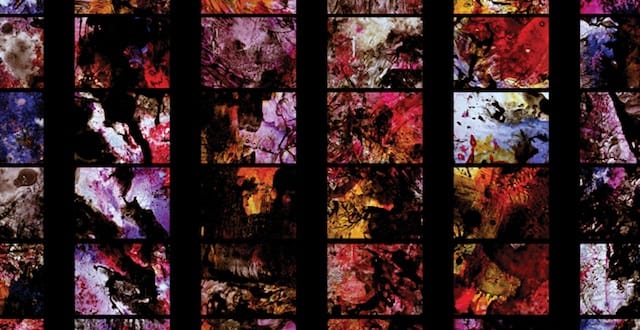

Images by Stan Brakhage