The Year in Architecture

Header image by Cur3es

///

It’s a yellow night in central Bristol, the city’s tungsten spill bouncing off a ceiling of low cloud. In an uneven alley, a single ellipse of white sits ominously on the pavement—a clean edge among the bricks and graffiti. It is one of eight such lights that are scattered across the city, shining in among trees in an empty park, tucked into the shadow of apartment block, or waiting along the roadside waiting to be discovered. Pass under one of them, and you’ll cast a shadow, as with any streetlamp, but idle a little and your shadow will be joined by others. The other shadow might dance, it might crawl, it might spin across the white ellipse and disappear out of sight. Or perhaps it will just flicker by, the trace of someone with somewhere to go.

This is Shadowing, a distinctive architectural project supported by the Playable City initiative. Coming to prominence in 2014 with international collaborations and a conference, Playable City presents a challenge to the vision of architecture as a purely functional space, envisioning itself as a response to the concept of a utilitarian “Smart City.” Shadowing was the recipient of this year’s award, a project which saw streetlights installed in Bristol that recorded the shadows of those who passed under them, and then played them back later to other pedestrians (not dissimilar to the ghosting that occurs within the Dark Souls series). The result was chance encounters between people whose paths cross spatially but never within the same time scale.

The project was hugely successful, encouraging Bristolians to break out of their routines and perform shadow shows for anyone who might pass later that night, providing a reminder of the way in which we unknowingly share urban space. In its transformation of architectural spaces into potential sites for improvisation and expressive play, Shadowing presents a compelling realization of the idea of playable architecture. Unlike services such as Foursquare, running apps and augmented reality, Shadowing is not simply using big data to gamify real-life space, instead it is drawing out its playground potential. This is why the project stands as a manifesto for the kind of projects Playable City actively supports—a view of architecture as having a wider, more human potential for play.

However, translating this capacity of architecture into a purely digital space is not easy. Games, by their very design, tend towards a focus on the function of architecture rather than its from. Take the platformer, or the cover-shooter, for example. Both genres build their entire architectural languages around basic contained blocks, arranged to serve the tactical and navigational possibilities of the player. In the case of the cover-shooter, an environment built entirely around the regular occurrence of waist high-walls is always going to be limited in its vocabulary, and therefore its expressive potential. Though we might think of these game spaces as being spaces of play, in architectural terms they are spaces of function, designed to fulfill the a series of highly-defined characteristics, like any office-block or hotel. Breaking out of this utilitarian approach is difficult—games require a certain focus on function for their design to be realised. Despite this, game design and expressive, playable architecture are not mutually exclusive—as a handful of games released this year have proven.

A view of architecture as having a wider, more human potential for play.

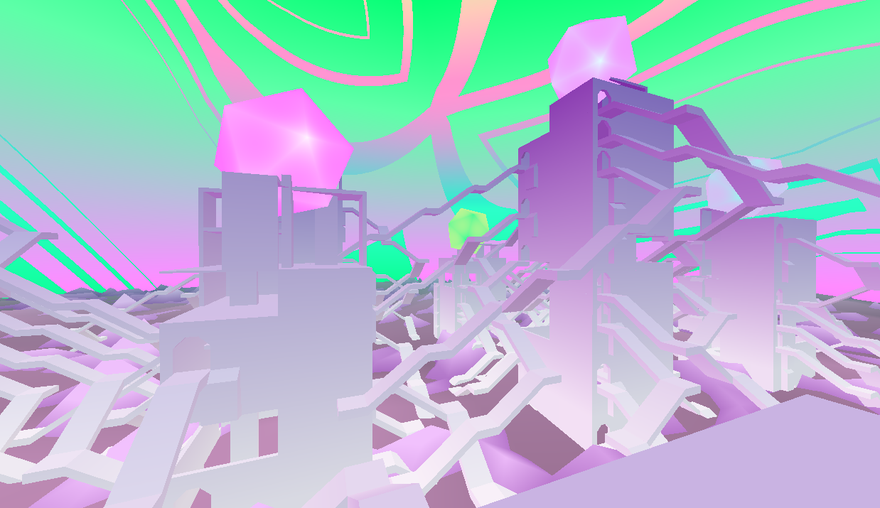

Abstract Ritual, developed by Strangethink, is one such game, marooning the player in a fluorescent world of illogical architecture and grumpy robed acolytes. It simply asks, as its brilliant title suggests, that the player performs a series of actions in order to open the hidden entrance to a secret world. The acolytes that dot its stark architecture give clues, but their ambiguity only further confuses the process. The result is the gaming equivalent of Jorge Luis Borges’ Library of Babel, where knowledge and noise mix inseparably, turning attempts at comprehension into futile wanderings. Most notably, the game’s architecture follows this same design, appearing like both a tumorous modernist housing project and a vast temple complex. The function of its rooms and terraces is obscured to the point of nonexistence, turning them into a playground for the floaty jumps of the player. This unity between the design of the player experience and the game’s architecture makes Abstract Ritual a hypnotic vision of what playable architecture might be—a space where meaning is made rather than read, and where rooms, walls and floors serve as poetic gestures not functional boundaries. Yet this architecture, strange as it might sound, is not so impossible as it might seem. In fact, at a distance, the boxes and ramps of Abstract Ritual’s weird world distinctly resemble the architecture of real-world architect Frank Gehry.

This year has been an important one for Frank Gehry. With two museums designed by the 85 year old architect opening within months of each other, and the first exhibition of his work opening at the Pompidou Centre he is experiencing something of a late-career flourish. Yet he has also faced some of the strongest criticisms of his work ever to surface, sworn at the press, and had his design for the Ground Zero Arts Centre rejected by its committee. His claims of “humanising” monumental architecture have been called into doubt, and accusations of his celebrity outweighing his skill have gathered momentum.

Yet Gehry remains one of the most important living architects, especially for those interested in the idea of play. Gehry’s disjointed, distorted and purposefully chaotic architecture rejects future visions of shimmering glass in favour of what has been termed “adhocisim.” Poor materials, expressive structures and the playful jumbling of recognisable features all make Gehry’s work some of the most distinctive and exciting in the world. In many ways his design philosophy chimes with that of Playable City—a rejection of utilitarian principles of design in favour of human interaction and play. In fact, at the opening ceremony for the Louis Vuitton foundation building this year, a chaotic structure inspired by park playgrounds and dreamlike vessels, Gehry said to the curator, “I made you a violin, now you have to play it.” This philosophy—that the architecture itself requires play to be activated—is a revolutionary one, and a very useful one for thinking about architecture in the context of games. But Gehry’s genius doesn’t just lie in his positioning of the Louis Vuitton Foundation as both an instrument and a playground, but in his understanding of architecture as an expressive medium. In his metaphor of the violin, the inhabitant of the architecture is empowered as the catalyst through which the potential of the space can be realised. In this exchange the architecture becomes the expressive object and the inhabitant becomes the player.

This philosophy is a revolutionary one

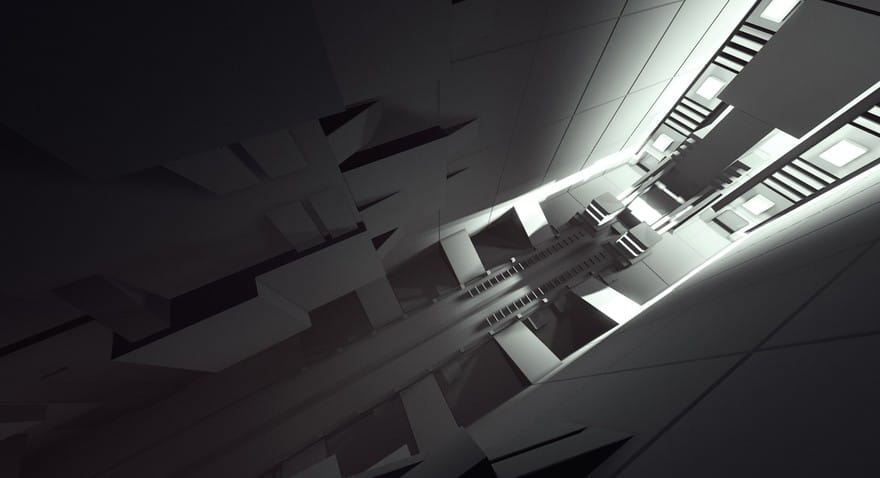

This year’s most successful and distinctive realisation of this “playable” architecture is the game NaissanceE. Developed by the small team at LimasseFive, this first person adventure excels in providing a restrictive minimalism that results in an expansive exploration of the expressive potential of architectural space. The basis of the game is simple—the exploration of a dizzyingly vast complex of stark monochromatic architecture. Yet in its stripped-back narrative and aesthetic, breathing room is given to the architectural construction of every room. The game begins in a world of primitive shapes, basic blocky arrangements that feel like digital versions of ancient monoliths, simultaneously a lost past and an unrealised future. But as you descend into its labyrinthine world, staircases, pillars, and elements of classical architecture begin to intrude. There is a moment when you encounter your first set of curved arches, coming upon them like an archeologist delving into a lost civilisation. But by the time textureless furniture appears and apartment blocks and cyberpunk skyscrapers are formed from greebled sci-fi surfaces, it becomes clear that there is no history to be found here. Instead each of these elements is a complete realisation of expressive architecture. The chairs and tables that lie around a room have nothing to do with realism and everything to do with affect, just as the steam vents and overlapping bridges are there not to build a world but an atmosphere. During one memorable descent the references blend and buffer together like half-remembered dreams: Fritz Lang’s Metropolis giving way to Blade Runner, and Grand Central Station interlocking with St. Josephs of Le Havre.

The result is an expressive architecture of memory, history and emotion that is totalised into an ornate and obscure physical language. NaissanceE is an expansion of Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Imaginary Prisons, oppressive spaces that are enticing in their complexity and ambiguity. Yet, unlike Piranesi’s sketched potential spaces, NaissancE represents an actual space of exploration and play. It is true that the game is often a platformer, asking players to complete jumping tasks and puzzles, but the game’s architecture never fully secedes to that function. In fact it often presents dizzyingly ornate structures that offer more dead ends and discoveries than paths forward. Those paths forward involve the player exploiting geometry as if they were testers, trying to break outside the game’s invisible walls. Ultimately its architecture is as unfocused and playful as that of Abstract Ritual. Both games present an architecture which refuses gamification, remaining oddly dysfunctional. It is through this dysfunction that the space is made for the realisation of an expressive architecture that supports and encourages play openly. The meanings you bring to the readymade spaces of Abstract Ritual and NaissanceE are supported by its architecture, much in the way Shadowing supports individual expression. In all three cases architecture becomes important only in relation to the individual experience of those that pass through it.

Play sees the world as a place to make and unmake meaning.

Playable architecture is a design experiment, a challenge that pushes architects, engineers and artists to conceptualise a human-shaped world beyond function and the drive for efficiency. It opens up routes into expressive, human and playful architecture that can be powerfully liberating. Schemes like Playable City, and works like Shadowing, Abstract Ritual and NaissanceE understand this, emerging out of a worldview that refuses to accept data as the final realization of space. To play does not mean to be free; instead, play sees the world as a place to make and unmake meaning, and architecture as a powerful tool to do so.