Yoshi’s Woolly World is cute, but confused

If you want us to cover more adorable games, consider backing our Kickstarter!

///

wool·ly

?wo?ol?

adjective: wooly

1. made of wool.

“a red woolly hat”

synonyms: woolen, wool, fleecy

2. vague or confused in expression or character.

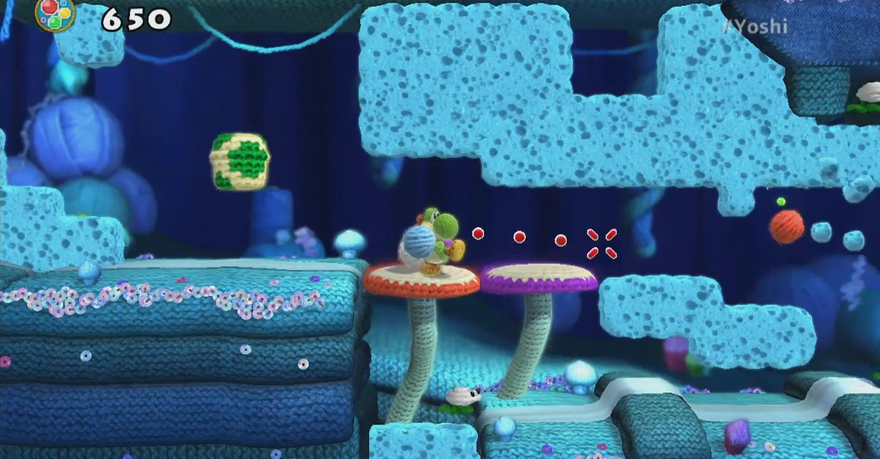

“woolly thinking”

The defining characteristic of Yoshi’s Woolly World—teed off by that alliteration in the title—is its aesthetic: yarn and glue. That woolliness bridges the gap between stereotyped gifts from grandma and the twee squeak most every Etsy storefront seems to be trying to wring out of you. This game is bright, soft, fuzzy, and unabashedly so.

If its defining characteristic is this set of aesthetics, we might think of its overall aesthetic category as the handmade. And that, in the context of a videogame, creates an interesting problem of representation: The value of the handmade is its singularity. Something handmade is, by definition, a one-off. It has little asymmetries and missed stitches that betray the human hands that made it. The handmade is literally irreproducible.

But Yoshi’s Woolly World has already been perfectly copied onto millions of discs, packed in boxes, shipped to near-identical GameStops and Amazon distribution warehouses, and sits waiting to be dropped into the disc trays of Wii Us the world over, where it will reliably boot up and display adorable yarny dinosaurs who connote the handmade to all who play it. Something about this seems off. There’s a friction between Woolly’s aesthetic goal and its medium.

Which immediately points us to a bigger question: Why, in 2015, is this sense of the handmade so desirable, especially when we’re constantly reminded in playing a game like Woolly that it’s illusory? To move the question to another part of the economy, why have companies like Etsy and Airbnb been so successful in commodifying authenticity itself? How is it possible that we’re looking for solutions to the problem of irreproducible experience in technologies that are valuable only because of their own reproducibility? The handmade and the main power of the digital—copy-paste—are antithetical to one another. Why the forced marriage?

The integration of crafts and code is not without recent precedent. Tearaway remains the best argument for the existence of the PlayStation Vita, and it makes much cleverer usage of its haptics in a craft context than Woolly World does. Tearaway takes the integration of crafts and play seriously: the player’s involvement in one informs the other. For example, in one level you cut a folded sheet of white paper and it becomes the snowflakes falling around a mountain. Nothing like this happens in Woolly; the yarn is a visual truth, but you’re not asked to do any knitting or crocheting. (I was especially surprised to find a Yoshi made of yarn could hold fire in his mouth.) Occasionally Yoshi’s body reconfigures itself into another form—umbrella, motorcycle, mechanized mole, etc.—but that’s hardly a function of knitting as much as it’s a mechanic from past Yoshi games yarn-bombed into this new context. There’s a too-easy argument to be made where I fault Wooly World for simply not being Tearaway, but that’s not what I want to do here.

Why, in 2015, is this sense of the handmade so desirable?

Games starring Nintendo’s egg-laying, fruit-gnashing dragon go back to Super Mario World 2: Yoshi’s Island (1995), which, as far as game feel is concerned, is almost no different from Wooly World. I don’t mean this as a criticism: Nintendo prizes refinement of past ideas above the idea that originality should be the measure of value. This is a commonplace about Nintendo—often used in a derisive way—but I think it bears mentioning that most of what we call “the AAA space” works in the same mode, albeit somewhat quicker (e.g., there have been 16 Assassin’s Creed games since 2007).

So, yes, Woolly is more of an update than a departure. It’s mechanically similar to Yoshi’s New Island (2014), minus the childcare. Instead, Woolly asks you to rebuild a community. Kamek rolls in on his broom and turns all of your friends into balls of yarn. Their body parts are scattered across the land and you have to go piece your friends back together. It’s straight out of a Russian fairytale, gore and all.

Woolly’s gameplay has sharper teeth than you might expect, given its plush exterior. That’s partially because of Mellow Mode, which is akin to the gold tanooki suit from recent Mario games. If you die more than a few times in a row, the game unsubtly reminds you that Mellow Mode (wings, extra health, etc.) is an option. There’s an irony here: If Mellow Mode is meant to prevent frustration, the game constantly reminding you that you’re not good enough to play it might actually be more frustrating than the challenge itself.

As a game, Yoshi’s Woolly World is consistently fun with the occasional devilishly well-hidden item, yet strangely unremarkable. In a lot of ways, it’s the ludic equivalent of the James Bond series: You watch it, and you enjoy it with the expectations you bring to a “flick” but never a “Film.” But, in a few months, someone asks you whether you’ve seen Quantum of Solace and you genuinely have to think for a minute about whether you saw that one or, wait, was it Skyfall? You shrug noncommittally before walking in to Spectre.

The way Woolly tries to disambiguate itself from its similar albeit less polished predecessors is with its handmade aesthetic. But that’s exactly the problem with the aesthetic itself: It’s literally repackaging Yoshi to avoid accusations of copy-paste. By trading on the unique and irreproducible qualities of the handmade, Woolly tries to conceal its other debts.

it’s the ludic equivalent of the James Bond series

This is an ethos that’s everywhere today. Apparently, we want the cachet of making the socially responsible, ethically defensible purchase that puts money in the pocket of a Real Person rather than a Corporate-Personhood Person without the messiness of actually engaging in an economic relationship with a Real Person. This leads to the creation of Corporate Persons who facilitate and lend an air of legality to the formation of economic relationships among Real People. On Etsy, you order something handmade(ish) from an individual seller, but you pay on a web form and it still arrives in a cardboard box dropped off by UPS. But doesn’t that cold emergence from a preformatted store page on the internet into the real violate the basic tenets of the handmade, since the handmade connotes a relationship between people? That you know the hands who do the making?

Where Woolly World is concerned, this line of thinking goes too far. I think Woolly has its thumb on this cultural idea of our increasing alienation from consumption, and plays it to pragmatic ends. Yarn helps them bridge the gap between binary bits and the player. But it’s precisely because we want to feel this connection that we’re so thoroughly deceived by it, and that makes the deception all the worse.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.