I first met Zach Gage ten years ago when I was living in NYC, and he was teaching at NYU. One of the things that excited me about game-making in New York was the interdisciplinary approach that many creators that had taken. In the absence of a large commercial video game making scene, like the one found in San Francisco or Montreal, video game creators often floated in and out of other mediums like architecture, graphic design, and interaction design. There was no big game studio that was looking to swallow up game creators, but there were plenty of other influences on the space.

Gage’s work since then reflects an itinerant nature that’s jumped from fonts to sound design to performance. Oh, and there’s some Proper Videogames thrown in there like Typeshift, Really Bad Chess, and Card of Darkness. The throughline of all his work is a deep love and exploration of systems and the generative behaviors that they create in players.

I spoke to Zach about jumping in and out of video games, learning from his audience, and the nervousness of watching people play with your work in front of you.

How did you get into creating things? Did you come from a family that did that?

My great-grandfather was a painter, and my grandma did painting and show posters for Broadway. My grandpa was an art director for advertising, and my mom is a painter now. My dad was a carpenter. Everybody was into art or an artist.

Did having that background impact the way you viewed the arts?

I never really thought about that. It almost certainly is true, at least of my mom. We would go to a lot of art museums. My entire understanding of art was framed in her explanation of painting to me, and art, and what’s interesting about it. That’s become my perspective, so it’s difficult to separate what her perspective would be.

I don’t know if this is what everybody learns about art or not. For me, the main thing about art is that pieces operate as lenses. They’re a thing that shapes the way that people see through them, and not a presented concept. Thinking of things as lenses really opens up what a painting is, or what a sculpture is. It makes it a lot friendlier because it’s not about you understanding it. When you look through a lens, you don’t think about what the lens is. You think about what you see through the lens, and that’s what art is. That’s what’s magical about it. It’s a very welcoming and open perspective.

College was where I was doing a lot of interactive conceptual art. That’s the time where I was really thinking about the theory and how I talk about stuff. That’s where I figured out a lot of my art language, and I would apply that stuff to the games.

For example, during that time, I learned how to make something that someone will walk up to and use in the gallery, which is a very weird thing to do. Nobody’s expecting to interact with anything in a gallery. Being able to set up a context and present helps people feel comfortable—like they’ve mastered the thing—so that they can perform it.

Performing is what they’re doing when they’re surrounded by other people who are watching them interact with the work. That concept is so hard in a gallery, and it’s so much harder than a game, but it’s what I think when I make a game. I’m thinking about how someone’s going to interact with this thing over time. That’s where I learned that skill.

When did you start dipping into games more formally? And then back again?

I did a little dip into games, and then after I went back to more traditional art. The first piece that I made was called #Fortune, which was this little box that searches Twitter for a bunch of different phrases and then uses them to generate fortunes for you.

When you interact with it, it’s a box in a gallery and a button. You push the button, and it pops out a little fortune, and then you laugh. I had scattered a bunch of fortunes on the box itself to get people comfortable and understand that this a thing. And then they interact with it, and as soon as one person does it, it draws a little crowd, and everybody’s really happy. It’s the joy of pushing a button and then getting a joke, which is really a very game-y mechanic.

That’s the core of loot boxes and all kinds of components of games. When I dip back in art I use the language of games. And in games, I use the language of art. So the loop is complete.

We had a conversation with Cassie Mcquater, and she was saying how much harder it was to show games at gaming conventions because people aren’t as willing to be confused. In an art context, she said, viewers came in with a mindset that it was okay to not quite know what was going.

That’s true when anyone walks into a gallery unless they’re like an art collector or a historian. [NYU Game Center Director] Frank Lantz has said that the joy of going to galleries is that you don’t really know if the thing you’re looking at is good or bad…and you also don’t understand it. You’re trying to figure out all of these things together.

But the thing that is happening in games, the reason why people have this expectation of understanding, is that literacy in games is so much higher. Literacy in art is criminally low. It’s impossible to totally grasp everything in art because that’s what art is about, pushing further and further. But also most people go into The Museum of Modern Art, not expecting to understand what they’re going to see and that sucks.

It feels like people should have a stronger sense of how art works. I frequently think about how I rarely see journalism about art in everyday life. You see journalism about movies and games and politics, but almost nobody’s ever writing or talking about art. Gallerists have somewhat been incentivized to mystify it.

I learned how to make something that someone will walk up to and use in the gallery, which is a very weird thing to do. Nobody’s expecting to interact with anything in a gallery. Being able to set up a context and present helps people feel comfortable—like they’ve mastered the thing—so that they can perform it.

Whereas games, there is actually massive literacy amongst gamers. It’s a commercial format, and it’s a relaxing format, so people are expecting to get the thing that they expect, that will comfort them and chill them out. They have a very high understanding of what the pieces of the game are and how they interact with each other. Even if, as developers, it often feels like people who are complaining don’t understand. But really they do, compared to a lot of other things. The literacy of videogame players is as high or higher than most of the people who are listening to music or watching television, in terms of how those mediums are structured and interact.

I had this moment a very long time ago with a piece that I did called Lose/Lose. It’s this game like Space Invaders, but the aliens kill your files on your computer when you kill them. I never expected anyone to play it. I didn’t really expect people to talk about it, because it flew in the face of the expectations of people who play games to such a degree that they were enraged. But there were only thousands and thousands of threads of people calling me an asshole and being really upset.

I read all of these comments. It was amazing to me that people cared about the thing that I had done. Buried in one of the forums, one player was describing art to another player and explaining how Lose/Lose was art. But they never used the term art, because they didn’t really know what art was. They had stumbled onto this concept. It was so mind-blowing to me that someone could put that together. All these people, thousands of people know what art is! They can discuss it and talk about it, even if they don’t think of it, in that way.

How do you describe what it is that you do, then?

I usually say I’m a conceptual artist, and I make videogames. A long time ago, when I was trying to figure out if I should stop doing as much traditional art and start making more videogames, I was worried that I was going to do something that was not important. I was giving up something that was maybe really cool and interesting and unique and meaningful, to make entertainment for people.

I definitely still dread when people ask me what I do, and I say I make videogames, and then they say, “Oh, what platform?” And I say, “Mobile games.” That sucks. I wish that mobile games had a better reputation because they’re the most interesting, most important context for games that we have right now.

Now that I’ve made games and I have an audience, and people write to me and talk to me, I hear a lot more stories about the way that people use games. They tell me how meaningful games can be to get people through tough times in their lives or as a part of daily rituals, in a lot of ways that I didn’t understand. I really have enjoyed videogames, and I know games can bring people together. Still, there were a lot of nuances to the way that games and entertainment fit that is much more important than we give it credit for.

There’s a lot of that that gets embedded into these objects. Games and art are creating these historical objects that document the way that games have moved through culture, what people have resisted, and how those things can be interrogated.

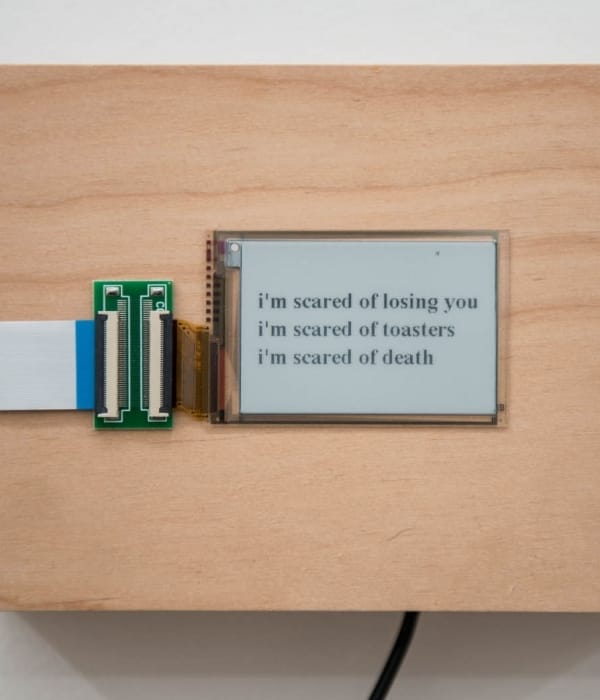

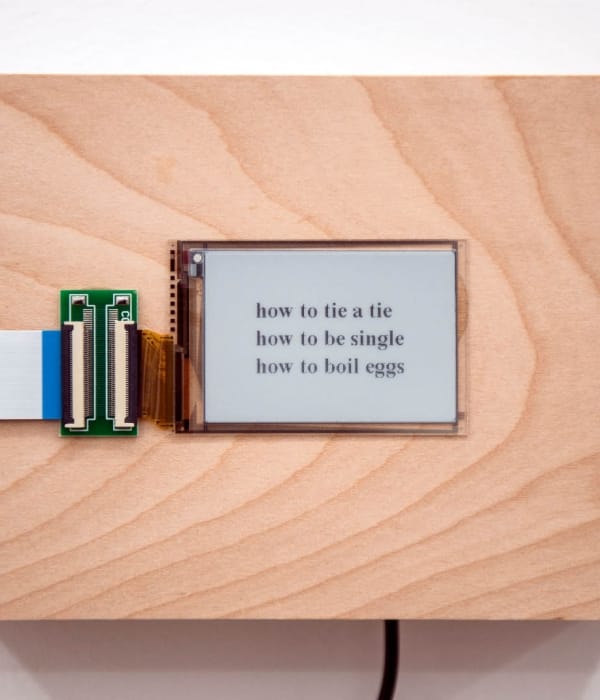

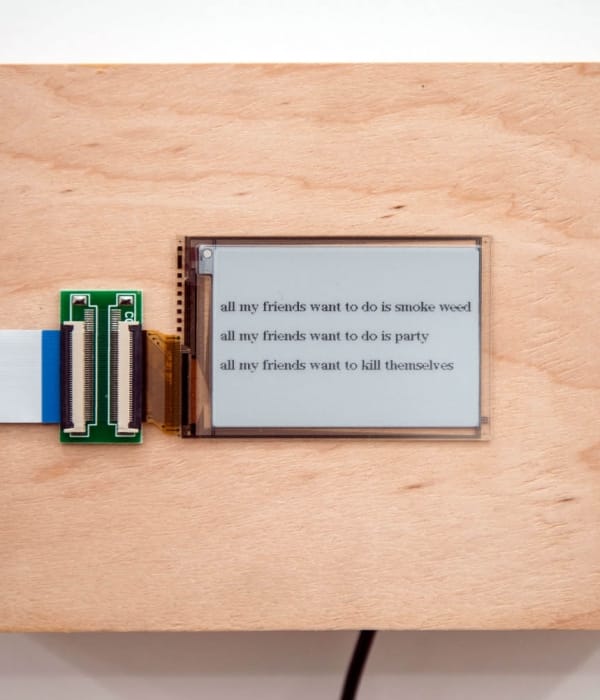

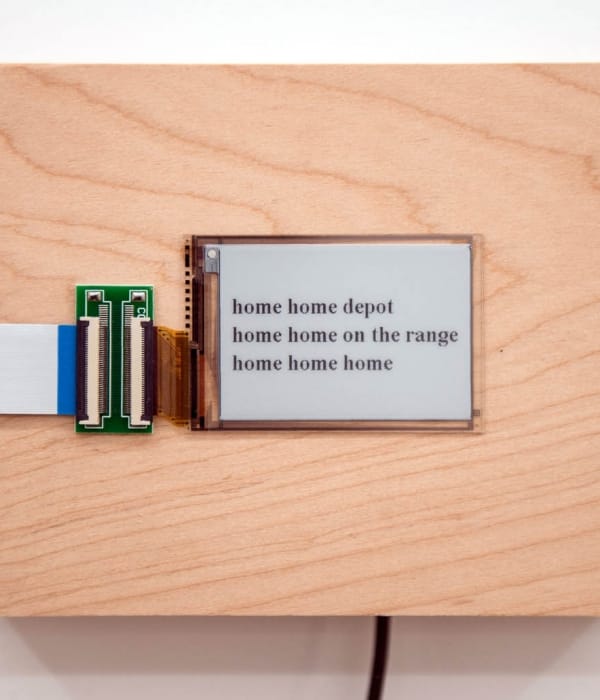

Glaciers (2015) generated unique poems daily from Google auto-complete prompts.

Games are this commercial medium that lots of people can purchase discretely and at a low cost, compared to art. How have you navigated that balance between selling a lot of a little thing and a little of a lot of a thing?

I had a series of pieces called Glaciers. A big part of that piece was that I wanted to create something purchasable but still felt unique. It was frustrating to me that most of the work I was doing was one-offs and that it had more emotional value to me than tangible value to anybody. A lot of the work that I’ve done recently has been about thinking of ways that people can repurpose things that they already have as frames for interactive works. What are the ways to use all of these old phones or tablets that everybody’s accumulating and turn them into sculptural works? Like a guerrilla usage of old things.

Last year, you did some installation work. How different was that from working in a digital context?

Transit Meditation very much was a game structure. It’s a labyrinth. It’s a game that only has only one path through it, but yet you can lose. Transit Meditation is, expectations-wise, sort of like a Kaizo Mario game (hyper-difficult user-designed versions of Super Mario Bros. games). You start it, and it seems like “Oh, this is easy, I’m going to walk this path.” Then you are walking it for about 30 seconds. You’re like, “Oh my god, wait a minute. This is not what I expected, this is way longer than I thought. Do I even have time for this? I thought this was going to be a quick thing. This is very boring.”

Either you duck out under the barricades, or you go, “Well, I’m not going to be beating by a bunch of stupid barricades. I’ll get to the center, then I’m going to walk back.” By the time you get to the center, you feel this accomplishment about having done it and having resisted this pull to bail. And it’s very cathartic, and as you leave, it feels much shorter than you went in because you’re not fighting a fight anymore.

Is it harder for you to make games in public or video games?

It’s still terrifying to release a video game, but the consequences for people not liking it are pretty low. But if you made a 10,000 square foot labyrinth in the middle of a big courtyard and buildings, and then it turns out it’s boring to walk through—and there’s no upside—it’s very scary.

With the Glaciers show and then again with Transit Meditation, the weirdest thing about doing physical installations is there’s no analytics in real life. You never really know how things are—if people like them or if they don’t? You do something in the real world, and I’m watching people, and they seem like they enjoy it. Is it a lot of people? Is it a little people? I don’t know! No one knows!

Credits

Interview by Jamin Warren on Februrary 19, 2020.

Photography by David Evan McDowell. Photography of Glaciers, courtesy of Postmasters Gallery.