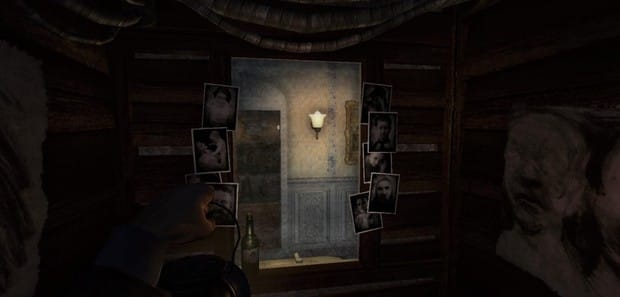

Dan Pinchbeck is happily married, good-humored, a caring dad. But when he sat down to pen Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs, all that went out the window. In constructing the persona of one Oswald Mandus, his protagonist who, shall we say, has some guilt on his hands, hez notched out the tortured mind of an irredeemable man. I talked to him in the U.K. the other morning, his wife Jessica Curry (co-director of the studio, composer, sound design) also chiming in.

(Content warning: This article discusses extreme and sexual violence.)

KILLSCREEN: Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs opens with the well-known Samuel Johnson quote, “He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man.” What drew you to that?

Dan Pinchbeck: What we were really trying to get away from with Pigs was the simple idea that there are bad people and good people, and that bad people can turn good, and that good people have bad people in them. We didn’t want a main character who was easy to write off as a monster. This is a tragic story of a guy running away from the pain he feels—trying to make himself less human.

What about yourself? I imagine that to create a work of horror, you have to become somewhat beastly, so to speak. How do you get into that mentality?

Pinchbeck: You’ve got to just push and push, every time you think you can’t go any farther, until you end up in some really dark places. The baseline horror, cannibalism, child murder, that just rolls out. But the darkest thing in A Machine for Pigs is the question of whether it’s okay to kill hundreds of thousands of people to save millions. It’s a really dark place, because it’s a real one. It’s the same question that Hitler asked; that Stalin asked. It’s what was going on in the Balkans, Rwanda.

Hiroshima.

Pinchbeck: Absolutely. Justifying the death of a few to save the many. It’s really fucking horrible, because it’s us. This isn’t really about a monstrous clockwork AI. This isn’t about mutant pigs. This is about what people do to people all the time.

Were there ever times when writing the script got to be more than you could handle?

Pinchbeck: With the stuff about the children, specifically, I had to sit down and go, “Do I feel comfortable as a father with what I’m producing.” It’s about a father who kills his children. It’s hard to put that stuff in. That was difficult. If any member of the team said, “I don’t feel comfortable,” we pulled it out.

What got axed?

But you’ve got to push it too far to find out where that line is. If you tiptoe cautiously up, you’ll always fall short. That’s how you find something with a real edge.

Pinchbeck: There was a pig fucking a dead body. The problem was it just looked like the pig was raping someone. It started off fucking a female body, and actually it just looked like rape. So we switched it out for a male body, and it [still] looked like rape. No better. We were trying to make a point of how animalistic the pigs were. But it didn’t add enough to justify the schlock.

Jessica Curry: We were lying in bed together and Dan tapped me on the shoulder and woke me up and went, “Pigs fucking human corpse.” I thought, “Who the fuck have I married!”

Pinchbeck: But you’ve got to push it too far to find out where that line is. If you tiptoe cautiously up, you’ll always fall short. That’s how you find something with a real edge.

Your background is in theater. Did you ever play the really horrible characters?

Pinchbeck: I was a really, really, really bad actor, but I did do some acting. All actors want to play the bad guys. Macbeth. The darker parts of Hamlet. I almost got to play the main character in ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore—the most unrepentant, unreconstructed shit. They never try to humanize him or redeem him. He’s so bleak. There’s a real attraction in exploring that dark path. In games, most people come to horror games so that they can be freaked-out by something that’s repellently awful. But they know that if it’s too much, they can hit the off-switch. We wanted to make a game that keeps scaring you after you’ve quit playing.

We wanted to make a game that keeps scaring you after you’ve quit playing.

When you were acting, playing a dark role, say an Iago, and also when you were writing Amnesia, did you ever feel like the evil was still lingering around at the dinner table after work?

Pinchbeck: I was pretty much able to compartmentalize it. But Pigs came from a political place. There’s a throwback to the attitudes that were kicking around in the Victorian period in terms of a rich minority treating the rest of the world like fodder. Because of that, I really empathized with the anger. When that’s shoved to the extreme—when you take grief, absolute rage, loss of faith, mental illness, and everything else—it’s actually quite easy to create that kind of monster.