Andrew Thomas Huang holds as much respect for craft as he does concept. With a background that meshes CGI animation with cinema, virtual reality, and puppetry, Huang molds singular worlds with their own tightly-sealed, labyrinthine logic, populated by bodies and landscapes, both familiar and unfamiliar.

Huang served as one of the creative directors for Björk’s immersive VR experience, Björk Digital, made the Grammy-nominated video for FKA Twigs’ cellophane, and is a current participant of Sundance’s Screenwriters Lab, where he will develop his first feature film, Tiger Girl. We sat down with Andrew to speak about the childhood puppets that kickstarted his creative pursuit, how he will bring his animatronic skills into his forthcoming film, and the breaking from expectations placed on creators of color.

Have you always been a creator, or was that something that came later in life? Where do you chart your initial journey into making things?

As a kid, I made shit all the time. It was compulsive—drawing and painting was my main thing. I also was obsessed with The Muppets. I wanted to be one of those animatronic people that made robotics—I would watch the Labyrinth behind-the-scenes video over and over. I got the steer from my neighbor, who had a boyfriend at the time that worked at an effects studio. Their advice was, You should really hone your art portfolio. You should learn to draw well if you want to go into effects. So I went to USC and studied fine art, but intending to be near the film school to help out.

At that point, I had done some digital filmmaking in high school and realized that I wanted to be in charge of my own thing. I made a short film outside of the curriculum while I was in college. I put it on YouTube, back when the site was only two years old, and they would feature like, five videos a week. It went viral and kickstarted my directing career. I didn’t really know what directing was, but I knew that there were people that I admired that made music videos, like Chris Cunningham.

I thought, Maybe I could go into directing that way. I did music videos and commercials for four years, getting my hands dirty. I finally realized, You know what, I’ve learned enough. I want to scrap everything I’ve done. I want to come out with a new statement. I made a short film called Solipsist, an experimental film that involved puppetry, mixed media, and live-action. Björk saw it, and I worked with her and Thom Yorke that same year—it was a point at which everything crystallized. I’ve done a combination of music video, narrative, and interactive work since and have been able to do so on my own terms.

Was there a Muppet, moment, or skit that sparked your interest in puppetry?

I was just such a nerd. I would tape all the Muppet show reruns from the 1970s on VHS. I also watched all of the Fraggle Rock series. It was the work that Jim Henson did in his later life that was more ‘adult.’ You could tell that he was crystallizing his artistic ways. He spent decades making family-friendly stuff, and then all of a sudden made bizarre, super-spiritual things like The Dark Crystal. In these projects, there are the goodies and the baddies, but it’s hippy work. It’s totally inspired by Jung and alchemy. As someone unaware of that, you feel that there’s something magical about the universe.

One summer, the Henson company sent two puppeteers to schools in LA to do a puppet program. When I was nine, they came to my neighborhood and taught us how to cut foam patterns and work with some pretty industrial, toxic materials. I threw myself at it. I felt privileged to be growing up in LA; to have access to stuff like that. That was the first moment I thought, Oh, this is how you can sculpt actual puppets out of foam and use industrial materials to fabricate these things. Even though I was nine, I still was like, Tell me what you actually use to make this stuff.

Is there something about the craft of puppetry that has influenced your voice as a director?

Totally. As a gay Asian kid, I never saw myself represented. There was part of me that was a budding thespian—I wish I could act, but I was too shy. The idea of inhabiting something else by proxy was more comfortable. The Muppets are super-queer—they’re beyond human; they’re fuzzy. There’s something that felt more truthful about being a weird creature. I identified with that.

Inhabiting something by proxy was an entry point for me and continues to be when I make work. I like that additional layer of speaking through this puppet to tell stories or inhabit a character.

That’s what’s so great about [The Muppets]. The mechanics are so awkward, technical, cumbersome, but the effect is so sleight-of-hand and seamless. I love when all the technicalities disappear, and you’re totally enchanted by this living thing.

There are things that puppeteers do to make something realistic or natural that are not necessarily intuitive. When you work with digital characters, do you find it challenging to make them look realistic or move believably?

For sure. When I work with digital tools, I always try to find some human input, whether that’s motion capture or tracking a real performance. I get really upset when I see robotic, lazy CG animation. You see kids shows nowadays produced so quickly and cheaply, I’m like, Oh, kids are watching this stuff that has no life to it.

People get into animation because they like to see the way things move. They think, Why imitate real human kinesthetics? People make Looney Tunes, for example, to do all the squishy stretchy things—that is the art of animation.

When I see something that feels biologically believable—like when we shift our weight or make something through motion capture—there’s a look to it because it’s doing what kinetically, your body would do. To get that goosebumps feeling, you have to have some sort of visceral human-like input. It’s challenging, but I think as long as you’re mixing techniques and always involving some level of real performance, you’re going to get some of that feeling.

You’re conversant in a variety of tools. When you’re sitting down and figuring out what you would like to make next, where does the process begin?

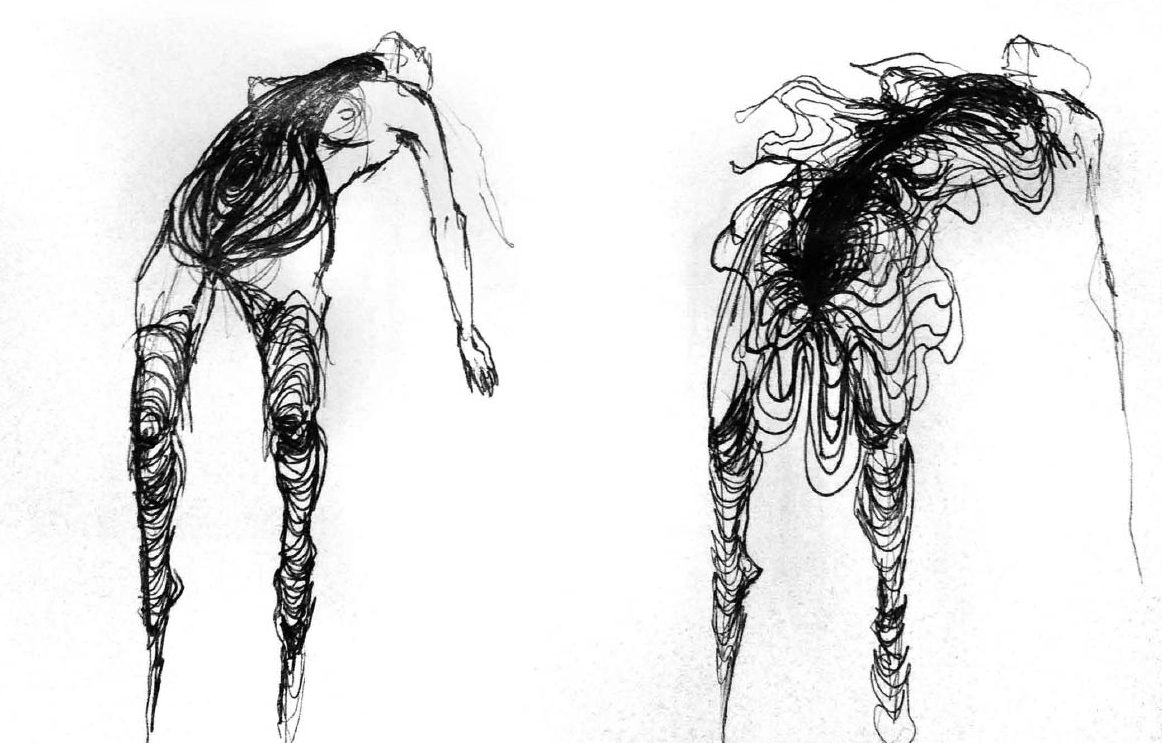

Usually, it’s drawing that comes native to me, but it depends. Sometimes, it’s a combination of regular pen-to-paper writing and drawing or a lot of research. If I’m working with a musician or another collaborator, it’s a lot of conversation. The music video industry is driven by these darts-on-a-board collaborations where they have multiple directors pitch on a track. I hate it when you see a video, and it has no real authentic threaded relationship with the artist. Whenever I enter a collaboration, I try to get to know them as people and understand what we’re conceptually trying to achieve with their music. How can I align with that visually? That’s when it becomes research, drafting, storyboarding, writing…I am a traditionalist in that way. I believe that writing—and, ultimately, pen-to-paper tools—are where I start.

One of the best pieces of advice anyone gave me was that when you make treatments or pitches, you want to create concept art that looks as if it had been plucked from the finished piece. So I go full-on. I’ll collage stuff from Photoshop or find images online that just marry together to look like the finished video. Sometimes, we’ll use that pitch and that artwork to raise money or guide the production. As a director, it helps if you give people a visual North Star for what your style is to be trying to achieve. Of course, there’s a script, and every voice that comes on your project will have their own interpretation. But if you’re doing something with world-building, you need the concept art to say, This is what we want this particular universe to feel like; this is what we’re striving for.

Regarding your collaborations with Björk, what is the process of building something interactive or multisite?

It’s not like we started out at one moment and said, We’re going to make Björk Digital. It was evolutionary. I made a video for her in 2012, and we reconvened a year later, and she wanted to do something different. She had a new album coming out, so we started with Black Lake, which was meant to be the center of her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. It was a combination of ideas and intuition on her part. She wanted to communicate what it was like to be truly in the center of this emotional experience, so she literally drew a stick figure and a dome around them.

We tried to make a 360° dome film in the museum, which was not possible financially because building a dome screen is extremely expensive. I shot Black Lake with an extensive tapestry format expecting to at least wrap it around a cylindrical screen. But it just didn’t work out.

We finished the film, but we were not able to create this immersive experience that we wanted. At the same time, Chris Milk was starting Vrse. works at the time, which evolved into Within. My producer during that period also happened to start working with Chris. So they had a prototype of the 360° VR camera rig with the GoPros that they were trying out.

In the narrative of Vulcinura, Black Lake is the death song. It’s the death of her relationship with Matthew Barney. In a way, it was almost appropriate that that was the last project we did in traditional film. For our next piece, it was like, Fuck trying to make a dome. We’re going to make an immersive experience with a headset. And so we shot our first VR piece that way, and it was very much an experiment.

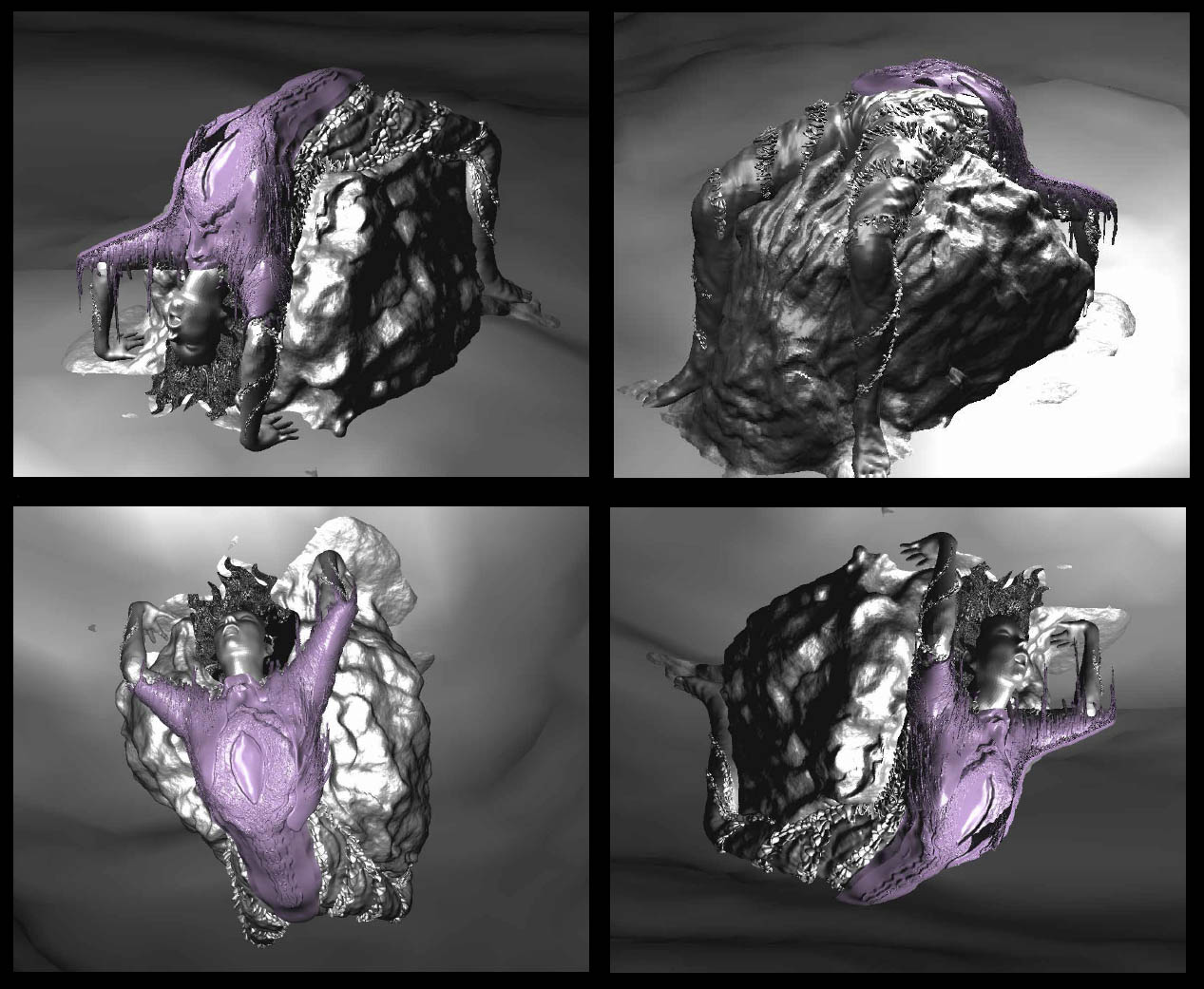

By that time, the technology was moving so fast. When we premiered that piece at MoMA PS1, it was like, Now volitional movement is more important—we have to build this in the Vive where you can actually move around. So for the next piece, we migrated to Unity and made it a proper game, but there was a conflict between the mechanics and making it a new musical narrative experience that changes through time.

“Inhabiting something by proxy was an entry point for me and continues to be when I make work.”

Programming the landscape to change throughout the song on a particular beat was tricky. As a filmmaker, it was definitely frustrating and challenging. I’d think, Can’t you just change the color at like one minute and 30 seconds? And they’d say, No, we have to program an interface to make that happen. Even then, it may not have occurred right on the beat because of the way the experience loads for everyone. Then there’s, of course, the question of 4D audio—at that time, it was still a relatively beta version of Wwise, spatialized audio where you attach sounds to objects.

That experience was my first true game experience, and I need to credit two developers, Vince McKelvie and Peter Javidpour. They were incredible problem solvers and both artists in their own right. It was so much to figure out how people come in and experience these pieces. How do we create individual rooms where people can have their own little chambers? I had also heard that sometimes people would experience my piece, but the shaders or the lights wouldn’t load. So as Family toured around, I wasn’t sure if it was being experienced the way I wanted it to.

But we also had byproducts—these avatars made for the experience that can then be used as motion capture puppetry for Björk. I also uploaded FBX files of these avatars up to Sketchfab, and people could actually tumble around these things in real-time. So that was a nice experience of taking what we built and spin out our characters, models, and sculptures in ways that people could experience interactively beyond what we created.

How are you defining a meaningful interaction for that work?

There are a couple of realizations that I had. One was how scale is viscerally impactful when you’re wearing the headset. The other had to do with hands. The mechanic of Family is that you’re sewing yourself through this journey, and we had these hands initially attached to the controller, but it felt like you were just holding them on a stick. I learned, though, that if you create a delay as you move the controller, the hand drifts, then it would feel like it was really your hand. If it’s connected to the control of your body, there has to be a delay or some kind of disconnect for you to feel like you’re actually controlling something that’s yours. Psychologically, I found that bizarre.

When you’re wearing the headset, there’s this desire to inhabit a space. For me, the climax of the video is very much like an Easter story. Björk has died and is resurrected. And once you discover her tombstone in the cave, you ascend through that tombstone and emerge on a sulfur plane—then she emerges as a giant goddess. The climax is her walking through your space; you penetrate the mesh at the height of the song. And you’re like, literally inside a giant Björk. I was touched to hear that people were in tears from that experience—they felt like they were really touching her in that performance and that moment.

In a way, that’s just an issue of staging. You can move around, but in the end, you’re still on this magical traveling carpet inside the ribbon sculpture that James Merry made. In a way, it’s still a passive experience where a character walks through you, but at the same time, you can volitionally experience it—you turn your head, and you can look around within that moment of embodiment. I thought a bit more about the way you stage theater or film, how often at the climax of a scene, the camera suddenly flips directions. Bjork walks through you, and the space flips.

Can you talk more about the viewer’s expectations coming into Björk Digital? They’re probably Björk fans and are explicitly trying something new. What’s interesting about coming from a non-interactive medium compared to one where users put energy into it?

It felt like designing a Disneyland ride. For instance, when you’re riding through Pirates of the Caribbean, you’re on a magic carpet, which is your boat, and there are many—Oh, I hate this word, but activation sites. Over there are the women chasing the pirates; over there is the animatronic chicken. And over there is the burning villa, you know? So there was pressure to fill in the blank page. When you have 360 degrees of volitional movement and space, there’s this tendency to want to fill it, but we just can’t, budgetarily speaking.

For Black Lake, we flew drones over all the sites in Iceland, and we also did photogrammetry scans of all the landscapes with a company called xRez. We thought, Oh, we might need these for visual effects purposes. But we also ended up using them for all the game landscapes in the VR piece. And that also became like when you experienced Björk digital—the home landing page. The photogrammetry scan on the landscape was enough for us spatially, and it was beautiful. I loved looking at the fine detail of this scan of a real location carved by a glacier—just letting the camera fly through.

In film, you’re always prioritizing where the eye is looking within the frame…and it’s no different in a game space. You can have an entire room that you enter, but there’s an activation site—a priority space that you’re calling for the game player to be drawn towards. For the latter half of the project, it was Björk’s tombstone and walking avatar. The same is for immersive theater—you can look anywhere, but you’re going to look where the action is happening. I think as long as you just prioritize what you’re emotionally trying to convey—and spatially where you want the user to be looking—then you don’t have to fill in everything. You can focus on what message you’re trying to convey, the action you’re trying to evoke.

Do you think that game makers are thinking more cinematically, or do you feel like directors are thinking more interactively?

I have so much reverence for game developers. They’ve been doing nonlinear storytelling for decades now. So hearing filmmakers be like, Oh, VR is a new pioneering way of storytelling, I’m like, What are you guys talking about!? Game designers have been doing this for so long. The only difference is that you’re wearing something on your face [laughs]. My opinion is more directed at filmmakers because I am one and see some of that rhetoric being spouted.

Nonlinear storytelling has been around for a long time. I love watching Ghost of Tsushima. It’s gorgeous, a total cinematic experience. I love seeing how Unreal is being used now in The Mandalorian to make virtual LED sets—that totally took my breath away with it when I first saw it. There’s a really cool convergence happening. I get annoyed when people are like, Oh, this is the first time anyone’s experiencing something like this. And I think, No, it’s not—there’ve been pioneers doing this work already. I just think it’s a common tendency for everyone in their respective sphere to have their head in the sand and not look at what other people are doing in other industries.

Now, there are tools that bridge the gap between what game makers and filmmakers know their respective literacies. Sometimes the game makers can be too invested in making a thing that’s simply an expression of a mechanic rather than trying to tell a good story, which can be just as simple.

Respective literacies is a good way of putting it. If anything, I get sad that VR is so difficult to share an experience with. After Björk Digital, I realized how difficult it is to disseminate that experience to as many people as possible. That’s why I still really believe in browser-based—that’s the most accessible, democratic way of sharing an experience.

Are you still working in Unity or Unreal?

The short answer is no. Unreal has been on my list of things I want to learn. I see so many people doing cool things in it, but I’m at a point where I just only have so much time to learn new tools, and right now, I’ve been just trying to get my feature film, Tiger Girl, made. Navigating into that space has been a whole new educational experience for me. My years working on Björk Digital was a great time of experimenting with this new platform.

I think about what they did with The Jungle Book where they built the entire forest in Unreal—it was such a cool application of the project. But I have to make a budgetable indie film before I can even get to that level.

Tiger Girl sounds so different, visually and narratively, from what you’ve made in the past. How do you see this as a new expression of your past work, as someone who’s worked with digital characters, interactive characters, and puppetry?

I’ve had trouble making the first movie precisely because of that problem. My stuff is visual, which means it’s expensive. It’s just expensive to make fantasy stuff. I would like my first movie to be as rich as Labyrinth, but that’s not going to happen.

There’s also this dilemma in the way filmmakers of color are marketed and sold or positioned in these labs or fellowships. Sometimes I feel like we’re only accepted into these if we’re telling some confessional sob story about our immigrant background or a kitchen-sink, socially-realistic drama. That’s not really what I want to do either.

So, I’m trying to merge these things. Why does telling a story about my family and their history have to be a social realist drama? Why can’t it be as magical as something Jim Henson would do? Tiger Girl is about a Chinese girl in the 1960s who discovers the tiger in her attic. There’s going to be a tiger—there’s going to be a puppet, and it’s going to be red, and we’re going to do cool tricks; some CG fuckery. That’s going to make it like mind-blowing, but I still have got to shoot with real people with believable emotions. Nothing’s worse than wooden performances in a visually lush film, and I also really hate it when I see something told with no visual imagination or style at all. So I’m trying to thread that needle.

But now, what I have to do is make this a good movie with good writing and good acting. And it’s hard! It’s the same as game design; how do you make a compelling story with beautiful mechanics and an entire world that you’ve created? It’s like learning to be ambidextrous. In order to do that, you have to kind of zigzag—I could stay in this territory where it’s purely visual and technique-driven, but I gotta work on these other aspects. I know, though, that we’re going to make it great.

I have friends that are so visually-minded and sensorial, then I have friends that are much more literary, who love narrative and acting. It’s like a different way of thinking. So we’re going to flip over to that territory and then try to marry this stuff together in the end, but it’s going to take time.

That challenge on the representation side is eternal for creators of color—it’s that balance between what kinds of things you’re supposed to be making. Sometimes, that aligns with what you actually want to make, but sometimes it doesn’t.

It’s important to tell those personal stories and tell them authentically. I also hope to depict those stories in a visual way that we haven’t seen before. Let’s hope I get it right.

Credits

Edited and condensed for clarity.

Interview conducted by Jamin Warren in September, 2020.