In 1540, cartographer Petrus Apianus created a rotating chart, or volvelle, that mapped the known limits of the stars above. He called it Astronomicum Caesareum. By moving this simple construction of paper and ink, one could trace the path of Venus or count the orbits of the moon. The project was a gift to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V. And now, nearly five hundred years later, Apianus’s ancestors can drive to Staples and buy a stack of that once-devine material for $8.99.

Ah, the humble piece of paper. Long before paper was a mainstay of the office world, it allowed artists and commoners both to imagine fantastical places, or create the fiction of a living, breathing creature through a few simple folds. Before the computer chip drew polygons or lines onto a video screen, a peasant’s fingers dragged carbon over paper to tell a story.

Now digital artists are going back to this ancient medium. From exploratory platformers like Media Molecule’s Tearaway, to interactive pop-up book puzzlers like Nyamyam’s Tengami, designers are building their gameworlds using that most nondescript of material. And that choice tells us much about those making and playing games today.

When we’re young, paper and games co-exist: We fold an airplane in class, we scratch out a tic-tac-toe grid on the back of homework. Then we grow up, get a job, pay our taxes. By then, paper’s transformative properties have long since passed, more often being used for the drudgery of daily life. “[Paper] as a material has more negative connotations in the adult world as we fight through mountains of paper-work,” says Rex Crowle, lead designer of Tearaway, the PlayStation Vita-exclusive game based in a papercraft universe. “But who isn’t delighted to hold a tiny papercraft toy or carefully open an intricate pop-up book and marvel at its construction?”

Sony’s new handheld has been billed as a full portable console, touting realistic worlds set in the Uncharted, Assassin’s Creed, and Call of Duty franchises. But Crowle’s studio, Media Molecule, known for LittleBigPlanet and its patchwork mascot Sackboy, hopes to tap into the nostalgia of adult gamers for those wonderful toys they used to play with, when a piece of paper was your next incredible machine, not typed up, stapled, and submitted for approval.

Many gameworlds evoke a kind of awe. But Crowle sees a disconnect between most game-players and the environments they so often explore. “The languages of normal-maps and shaders are not something a player can really appreciate,” he explains, “because most will not have created anything with that method.” Unless you yourself are a digital artist, the effort and artistry that went into that sheen of a dirty rockface glinting in the sun is unobserved. Good for immersion; not great for being awed by the creation of that world itself.

In creating Tearaway completely out of paper, Crowle and his team hope to evoke a different feeling than simple, passive awe. “By focusing on a material we’ve all experienced, and by using its properties and showing its construction methodology, I hope that some of that wonder can come through.”

Other designers must have gotten the same internal memo (on a paper sticky-note, no doubt). In the past few years, a number of high-profile games have released with a paper-based aesthetic: Nintendo and Intelligent System’s Paper Mario: Sticker Star, Broken Rules’ And Yet It Moves, Q Games’ Starship Defense. And more are on the way. But it’s not just a return to childhood favorites that pushes this trend onward. It’s the devices we use to play games themselves that is driving the choice.

“Imagine trying to play a papercraft game with a controller,” says Phil Tossell, co-founder of Nyamyam and co-creator of their first game, Tengami, coming out on iPad later this year. “Press X to fold, pull trigger to cut. Now imagine the exact same [game] on an iPad. I can see my fingers swiping across the screen to fold or cut the paper.” The prevelance of touchscreens has made it intuitive and simple to create games based on these tangible, real-world materials. It’s more than just a trendy visual style; it makes mechanical and creative sense.

Tengami takes place entirely within the complex folds of a pop-up-book. The character and worlds are rendered in a striking style reminiscent of traditional Japanese washi papers. “We wanted something that displayed the beauty of paper in its simplest of forms,” says Tossell. Everything about the game—its slower pace, the serene mood, the thoughtful puzzles—reflects the humble nature of a material we take for granted.

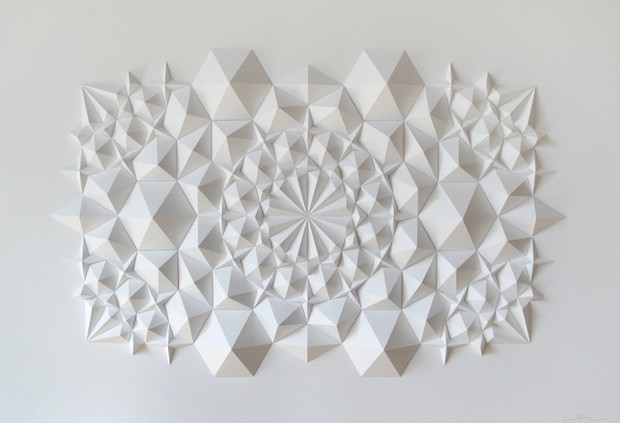

Even artists not making interactive games have found inspiration in paper. Matthew Shlian is an Ann Arbor-based artist and instructor at the University of Michigan. Much of his work derives from intricate, complex designs made by hand. Before teaching in Ann Arbor he was an artist-in-residence at Siggraph, the annual conference for digital arts and technology.

“I would set up a table across from the 3D modeling-interactive-stereoscopic-laser whatever and show people how to fold paper.” This simple technique held the attention of so many used to being on the bleeding edge of computerized design. “I would teach them basic pop up design, pleating systems, paper craft. People spent hours sitting with me in the middle of this barrage of technology and fold paper. They told me they missed making ‘things- objects of wonder. They said they sit at a screen and model characters or render things for hours and only have the work exist digitally.”

These two concepts come up again and again: of paper evoking a sense of ‘wonder,’ and the paradox of a digital thing not truly existing. Crowle and Tossell hope their games can bridge that gap between the tangible and in-, creating something lovely and beautiful and interactive in a way our childhood toys, that folded up paper football or a fortune-telling kaleidoscope, did so well.

One of Crowle’s favorite games as a child wasn’t the shiny new Atari or the electronic magic of Simon, but the word-guessing game Hang-Man. “For a simple pen and paper game, it had so much atmosphere and room for personal expression and storytelling.” The flexible, handcrafted element of creating the game while you played prepared Crowle for his future work.

“I’d embellish my little swinging corpses, sketching in misty moorland backdrops while my opponent tried to guess my (probably misspelled) word. And I’d always try and extend their life as much as I could, adding a moustache, and some glasses, and a fez, and a hearing-aid, and horns.” The classic paper-based game hinged on the same kind of user-generated details that made LittleBigPlanet so memorable. Playing Hang-Man “probably helped with my character-design art development,” admits Crowle.

Shilan: Ara 117

You can now download Extreme Hangman on your iPhone and play, tapping and pinching a screen instead of scratching lead into processed trees. Is all this paper-mania just a last-ditch effort to save an outdated medium? To touch and feel those tangible forms from our youth, if even just a facsimile?

The same anxiety crops up in every medium or artform: eReaders are killing books, CDs and MP3s killed the vinyl album. Local movie theaters are paying thousands of dollars to convert their film projectors to ones that read and play digital files; studios are just no longer making movies on reels of film anymore. We snap photos that forever remain locked in silicon. Newspaper publishers are folding up (no pun), moving operations online. Even the first videogames would run on a printed-out sheath of instructions. Now, everything’s encoded, molded by some ghost hands inside the machine. Is this paper renaissance really just a prelude to burial?

Tossell doesn’t think so. “To some extent the purely functional role of paper is being supplemented or replaced by screens,” he says. “So for me this really allows paper to be rediscovered as a purely creative medium. And if you look on a site like Etsy, you can see this is already happening.

“People are creating many wonderful things with paper.”