Always Sometimes Monsters is evil. Not the kind of evil that festers, or menaces. Not the evil that is opposed to good. But the evil of apathy, as proposed by Ayn Rand in her novel Atlas Shrugged, and which informed her Objectivist philosophy. In it, she wrote:

“There are two sides to every issue: one side is right and the other is wrong, but the middle is always evil … the man in the middle is the knave who blanks out the truth in order to pretend that no choice or values exist, who is willing to sit out the course of any battle, willing to cash in on the blood of the innocent or to crawl on his belly to the guilty.”

As with so many computer role-playing games, Always Sometimes Monsters is about making choices to determine the contours and outcome of its narrative. But, unlike so many of its peers, the game is open-minded and unemotional to the choices you make inside its modern day fiction. There are no Renegade and Paragon points. There isn’t even any combat. Rand may have viewed Always Sometimes Monsters, or rather its creators, as despicable cowards, but there’s a greater purpose behind its complete lack of judgement. This is an exposition of the role-playing we perform in our real lives (as opposed to a fiction).

The scenario that Always Sometimes Monsters begins with is one of the strongest examples of its engineering. Your book publishing deal falls through due to your character’s laziness. You have $13 to your name and less than 24 hours to find $500 to pay your rent. If you don’t then you’ll have to sleep on the streets. The easiest way to earn that cash is to steal money from your elderly neighbor’s bank card, and then do some extra work on the side. The harder option means trying to earn the $500 through non-criminal means. In fact, the tougher, more honest path may even be impossible, but as with life, failure doesn’t result in a Game Over screen. You’ll progress whether you generate the $500 or not. Later on, you’ll find other routes may open up that allow you to bypass other prerequisites (affording bus tickets, stopping a strike, winning back a car) of the narrative’s journey across the country to attend your ex-partner’s upcoming wedding.

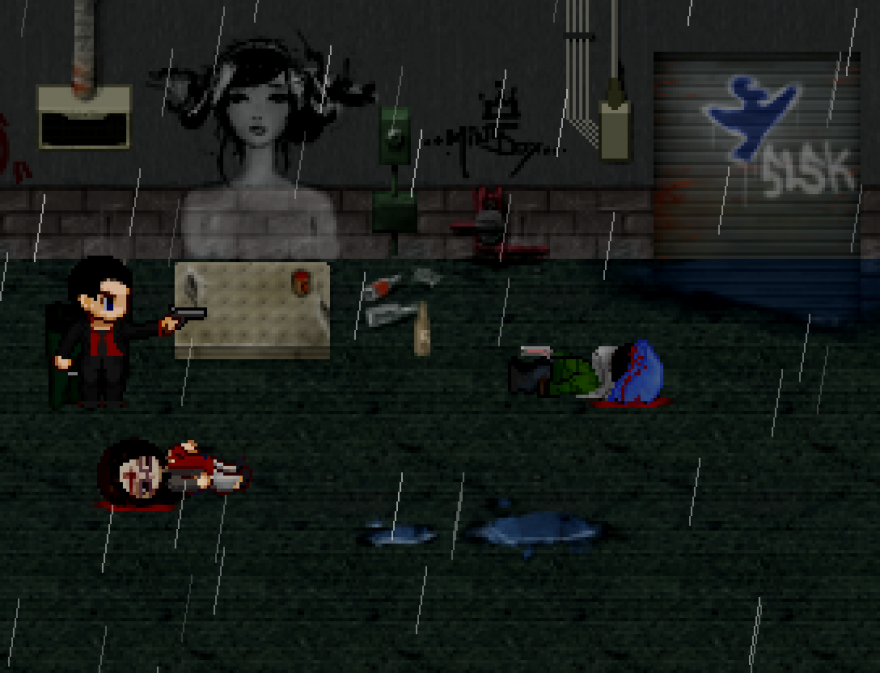

The “evil” neutralness of Always Sometimes Monsters is in its absence of any fundamentally right or wrong answers; there is no good or bad. The rules and enforcers of the society we are familiar with are nonexistent throughout, despite it clearly being set in modern times. This means that consequence is never synonymous with felony. Instead, the negative repercussions of your choices and inactions cause emotional, economical, or physical upset to others, sometimes even death. But the game will perceive you in the same way no matter what; whether you’ve murdered and robbed, or worked hard and slept on the streets.

This world without judgement or, at least, legal punishment has churned up its denizens and is lined with an omnipresent destitution. It’s embodied in the vagabonds you can converse with, avoid, and become. Progress in this world is found by transferring hardship on to others, or incurring it yourself. If you choose to not commit what could be perceived as a crime, you could place your fate in a higher power or, if you prefer another type of faith, trying to win big on scratch cards. Failing that, you’ll probably wind up repeating the same tedious actions in factories to earn the cash you need. It’s here that Always Sometimes Monsters does its best impression of Richard Hofmeier’s Cart Life and Lucas Pope’s Papers, Please; forcing you to feverishly perfect mundane jobs to become machine-like. You aim to grind harder for faster money. Unfortunately, it lacks the panache of these other two games, present in their focus on fumbling with coins, papers, and products. The constraints of RPGMaker means the best Always Sometimes Monsters can do is exhausting and rapid menu navigation. It’s the most basic RPG grind in a game that is otherwise so unlike other RPGs.

Fortunately, the larger picture that forms Always Sometimes Monsters is bigger than its technical limitations. As said, there’s an admirable reason for why it plays the middle man. It wants you to make the choices and set the rules that you abide by. This is revealed explicitly in one particular scenario that I experienced. “Are you judging me?” my character Clarissa asks Casey, who in turn—as the game’s only parental figure—speaks on the software’s behalf. Casey says it’s not her place to judge Clarissa and therefore myself, revealing that the game rests on the same impassive credo. Instead of judging me, the game takes the opportunity to invite a moment of self-judgement.

The delinquencies I’ve committed over the course of the game and jotted down in my journal are then read back to me by Casey. I’ve robbed an elderly neighbor; given toxic drugs to a girl to pocket some extra cash; broke into a city hall’s electronic mainframe to rig an election, and more. I did these things because my back was pushed up against the wall. I either had no choice to commit them if I wanted to progress, or I decided it was the better of two or more consequences. The question is whether I regret making these decisions or if I can excuse them. I am given only these two choices to judge my actions and cannot adopt the timid indifference that the game reserves for itself.

Here we see that the world of Always Sometimes Monsters offers itself as a vehicle for you to explore your personality (your politics and culture). It pushes tough choices on to you in order to squeeze your basal values and sensibilities out. It’s about making decisions and facing the myriad consequences of each of them; affecting entire towns, individuals, and yourself. Its thorough neutrality becomes a conduit for self-judgement; a mirror for us to see ourselves in and react to the monster we may have always been. The strength of it achieving this goal relies entirely on how well you can connect with its fiction. Like a cold reading, it needs “hits” to be effecting at all, meaning you need to perceive a line of rationality in the choices you make. You wouldn’t normally just suddenly snap and kill someone, or perform a similarly horrendous act on a whim, and so you don’t in Always Sometimes Monsters. There are always steps that can be traced back to these decisions, and each of them are, as the game’s opening statement says, “an evaluation of cost and benefit.”

No, that’s simplifying it too much. Decisions aren’t mathematical equations in life or Always Sometimes Monsters. They’re conversations you have with the voices in your head. They’re as complex and self-revealing as the rationale that causes you to shake your head and walk hurriedly past a beggar on the streets—What will they spend the money on? Food? Drugs? Will they attack me if I ignore them? Will they snatch my purse when removing it from its cosy pocket? Do these other people watching us think I’m heartless? What if I need that change later on today? These are the types of questions that you bring to Always Sometimes Monsters and that inform each world-altering decision you make. It’s a game that purposefully teases and implies the multiplicity of people and situations to allow space for your own elaboration. This is, in some small way, visualized through the typical top-down pixels of an RPGMaker game that it wears. Even the more luxurious portraits of the characters that appear alongside their dialogue are stiff, singular expressions—pointing upwards thoughtfully, beaming with a smile, hiding behind hunched shoulders and a hood. It’s as if that person had just one gesture with which to portray themselves forever, and it’s your job to fill out the rest of their persona. Getting to know each of them means getting to know the friction of each city, its high and lows, which in turn better informs the choices given to you, while at the same time the extra voices in your head means they become harder to make.

In making you aware of different viewpoints Always Sometimes Monsters overloads you with concern. It’s an attempt to portray the breadth of the human experience, and in taking it all in, you become sick with the interconnections and disagreements—you can only compromise and can’t “win” as you can in monomyth. These difficulties are all necessary for you to reach the game’s destination of self-discovery. But perhaps you have already, in your own life, dealt with similar conflicting issues underlying everything and have been shaped with this knowledge. In this case, as with my own experience with the game, going through simulations of real problems and conversations doesn’t really have the impact it’s supposed to. It’s for this reason that Always Sometimes Monsters will most likely resonate with those in their formative years. But that doesn’t mean it can’t help to, at least, further cement your understanding of your beliefs and how you’ve arrived at them. In fact, this is a result that is very clearly grasped at during one tangential conversation in which you’re asked directly what it is that guides your decisions: Love, God, nothing (Nihilism), or your individualism (Objectivism). But notice how limited this choice is when considering the large number of possible belief systems. What if you don’t relate to any of these choices? Then it’s possible that you start to become distanced from the game and that’s when it starts to unravel.

Not all of it coheres perfectly. When Casey read my more deviant choices back to me from my journal, one described a friend that had died in hospital because I didn’t help them. It was purported that I chose not to help this friend, but I didn’t know anything about them or their fatal condition, so it shouldn’t have even appeared in the journal (written by my character) as far as I was concerned. Similarly, when I forgot to feed my character, the Stamina meter ran to empty, which in turn led to my realization that it had no effect on my character’s health or abilities. This runs contrary to what the game leads you to believe in its opening sequence. It could also be argued that the game’s save system doesn’t pressure you to live with your choices enough. It allows for up to nine save states at a time, which means you can explore different paths and the permanent effects they have on the world, if you so wish. That seems self-defeating in a game about making choices and dealing with consequences. But on the other hand, having a wider sense of the possibilities at each node means that you can better determine the path that most suits you, helping to bring yourself into the decision.

Still, it’s the questions that Always Sometimes Monsters raises that matter. Its core principal runs parallel with another of Ayn Rand’s statements: “His own happiness is man’s only moral purpose.” Whereas Rand’s critics lambasted the selfishness of this notion, Always Sometimes Monsters finds a more empathetic spin on it, achieving the opposite effect. You’re encouraged to see beyond good and evil, instead seeing the rationalized choices that others make in their lives. Even more laudable is that it manages to provide an intimate journey for each player despite the breadth of human diversity.

But the game’s reliance on establishing such a personal connection in order to meet its noble goal of self-discovery does breed fragility. This becomes apparent in the game’s multifaceted ending, which sees the game’s creators striving to draw attention to the game’s artificiality. Attention is drawn to the puppetry in order to take you out of the narrative and to reveal that your choices were futile. Its final acts are similar to Hotline Miami‘s and Spec Ops: The Line‘s in that the cruel joke goes beyond “But our princess is in another castle!”, instead wearing a post-modern smirk equivalent to “There was no princess at all!” This will prove to be a divisive move on the author’s part. There’s a chance that this will make you feel incredibly empty and cause the rest of the game to lose much of its power and meaning. But, just as likely, you’ll philosophize further, debating the game’s messages for eternity, and hopefully coming away more aware of what is most important to you in life.