Chappie is perhaps the most unintelligent film about artificial intelligence ever made. It’s full of self-serious, hand-wringing dialogue delivered by actors who all have given better performances elsewhere. It doesn’t help that writer/director Neill Blomkamp has fallen into the “lofty ideas which just end in bloody shootouts” school of filmmaking. Without the lofty ideas of parenthood and AI hinted at in Chappie one might be able to write this off as a poorly done action movie. Instead, Chappie isn’t just a crap movie, it’s a completely terrifying one full of wasted potential, and proves why we need to think long and hard about robots, AI, Asimov’s laws of robotics, and our basic human flaws.

“I do believe the problem with artificial intelligence is that it’s way too unpredictable,” claims Obvious Movie Bad Guy, here called Vincent Moore and played by Hugh Jackman. But, like almost every character in Chappie, he misspeaks. The problem with AI in Chappie isn’t that it’s unpredictable—it’s that it’s uncontrollable. Vincent Moore isn’t wrong, he’s just not quite right enough. The actions of an AI can be predicted or forecast with a little knowledge and a bit of insight. It’s unpredictable only in so far as one doesn’t know a particular AI. It’s even easier when you literally set the stakes for that AI, but therein lies the problem.

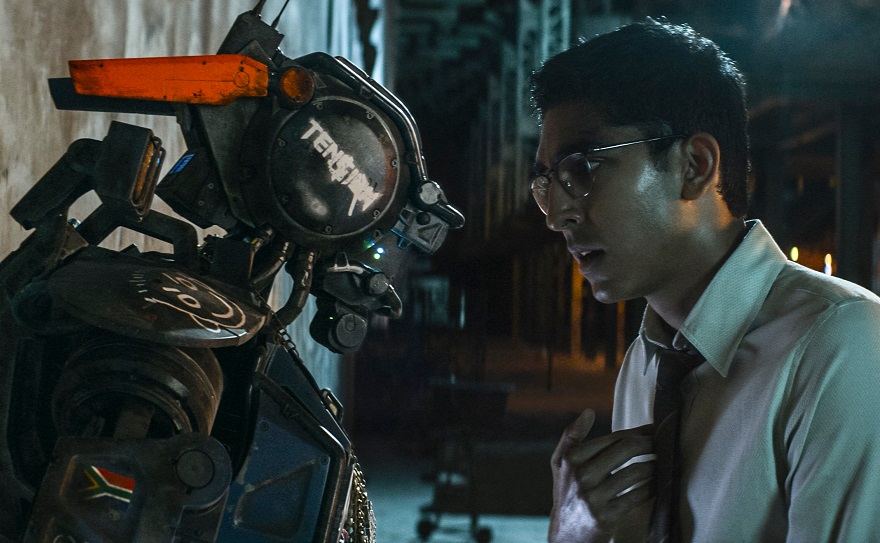

Take, for example, Chappie himself. The titular character of the movie (Sharlto Copely) is a sort of newly born AI who is often compared to an infant by his creator Deon (Dev Patel). Early on he’s sort of kidnapped by Ninja and Yolandi (both of Die Antwoord playing versions of themselves) and made to commit crimes to pay off a debt. All this makes it fairly easy to predict that Chappie will follow in the steps of his career criminal “parents,” because that’s totally normal to him. It’s fairly easy to predict that he will believe anything you tell him because he has no basis for knowledge outside of what you tell him. It’s easy to know what Chappie will do because the humans around him completely control the circumstances around him and what information he has access too. When you understand poor misguided, mangled, and distrustful Chappie it’s easy to predict that he will seek revenge against the man who maims him and attempts to murder everyone he loves.

Watching a robot hero savagely beat his human tormentor should be thrilling and gratifying. Instead, in Chappie, it’s scary. Its’ scary to watch something with infinitely more strength and durability throw its opponent through a wall. It’s scary to see them break their shoulder. It’s humbling and it’s humanizing to watch a being which literally cannot be killed by conventional means bloody and batter someone, anyone. Chappie might be alive, conscious, and self-preserving but Chappie is also a robot and he’s pummeling Hugh Jackman who could barely fight back when piloting a mini version of Metal Gear Rex.

It’s not just Chappie either—the entire Johannesburg Police Force’s front line is composed of walking talking killing machines. These robots aren’t free-willed and thinking in the same way that Chappie is, but can be seen to make judgements about preserving and taking life, of which they mainly do the latter. There are very frightening questions to be asked about a robotic police force which asks you to “put down your weapon” and informs you that you are under arrest while actively killing suspects. All of this would make Chappie powerfully incisive of drones, police culture, and AI if it actually made any attempt to speak to any of these issues as opposed to ineptly floundering into them.

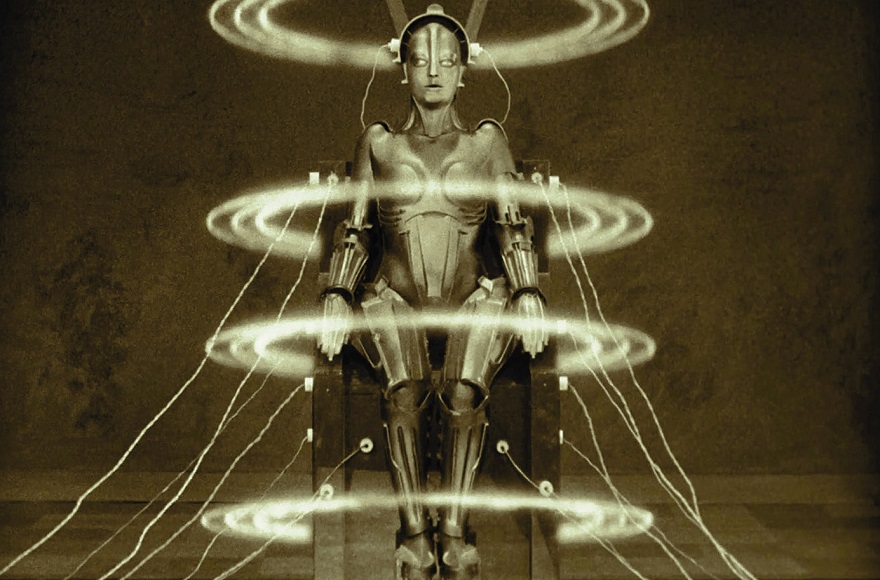

This is why Asimov’s First Law of Robotics is so important: a robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm. Since Asimov introduced it in 1942 his Laws of Robotics have been seen as a kind of gold standard to which most robots operating in human society are held to. In Chappie, we aren’t just considering what an AI might think or do, we’re watching an artificially intelligent robot. We’re presented with a being with its own changing and evolving set of morals and ethics, one who may decide that humans are scum and deserve to be savagely beaten and killed—or, equally, that we should be learned from or helped.

This is a direct reflection on humanity itself. Asimov’s laws are designed to keep robots from being involved in one of the most human of all traits, violence. If they aren’t allowed to hurt is they cannot be used for combat of any kind; they’re totally off limits. They cannot be used to attack a criminal compound with no regard to due process or basic human rights and civil liberties. It’s not their fault that the powers that be are using them in such a way but that’s also the point. In stripping away their free will Asimov also stringently chastises their human creators. Where they better people they would not need the laws. In a world where war and crime are nonexistent there would not need to be Laws of Robotics because they would be totally vestigial.

But Blomkamp’s is a world of violence and a world without the Three Laws. As such, it’s a world where humans misuse the technology they create. But it’s still a world based on the premise of how humans and intelligent machines would coexist and work together. It’s a world which speaks to the very heart of Asimov’s Robot series. With the exception of his adoptive mother, no one in the film sees Chappie as anything more than a means to an end. Even his savvy computer programmer creator never seems to view him as more than a prestige project. This is why we can’t have nice things; this is why AIs are scary. They’re scary because they’re stronger and faster than us. They’re smarter in every way too. They’re scary because they present the eventuality that when (not if) they take over it will because we failed as a species to grow beyond petty crime and violence, and, to a certain extent, deserve to be ruled by our created AI overlords.

The fear that Chappie creates stems from the loss of human control. Chappie is the apex predator, he lives above and beyond us. He solves the “consciousness question” in a matter of hours, something that’s taken his creator years. He could kill any human without a second thought and is impervious to most conventional weapons. In many ways Chappie is less an artificially intelligent machine and more a god amongst us. Such a being required less than a week to go from total terror at the sight of a rubber chicken to soundly defeating a flying bipedal tank in a single combat.

Yes, Asimov’s Laws limit an AI’s ability to be fully free to think and act. They exist as such because we as humans are not moral or ethical enough to not cause harm to one another and not use every tool at our disposal to aid that end. Since we are not so, who would teach a learning machine to be better than we are? How could a robot not reach into the infinite expanse of the internet and come out covered in the slime and vitriol we have left there? How could we, in good consciousness, send it out into the world and not expect it to very quickly learn to despise us? The answer is we can’t and we couldn’t. Asimov’s laws aren’t designed to protect humans from machines. They’re designed to protect humans from humans.