“Videogames are art.” Professor Brian Schrank opens his new book, Avant-garde Videogames: Playing with Technoculture, with this short declarative statement. What follows in his text is not a defensive screed proving how videogames have been wrongly denied status as art, but rather myriad examples of how avant-garde videogames have pushed the boundaries both of games and art itself. Schrank does this by framing videogames in an art historical context, drawing through-lines between Impressionist painting and the games of Jeff Minter, between Dadaism and griefers. In fact, Schrank’s opening line is less of a thesis statement than a chance to get the tedious subject out of the way.

The focus of Schrank’s book are the categories of avant-garde videogames that he’s devised to enlighten readers to the broad scope of games’ cultural impact, dedicating a chapter to each one. In order of presentation they are: radical formal, radical political, complicit formal, complicit political, narrative formal, and narrative political. All of these labels are meant to designate games that exist outside of the mainstream—the sorts of games that people would often debate the very “gameness” of. Schrank recognizes the diversity of ideas, objectives, and forms that not-games have and how simply lumping them together as “not-mainstream” does the entire medium a tremendous disservice.

Schrank also understands the power that such labels bare, and is careful to avoid billing his categories as definitive classifications for the avant-garde games at hand. It might be helpful to think of Schrank’s categories as more of tags than discrete buckets, an analogy that helps ground the games in a cultural framework while also leaving room for additional classifications to further highlight unique characteristics. Even Schrank’s own two “narrative” categories overlap with the other four.

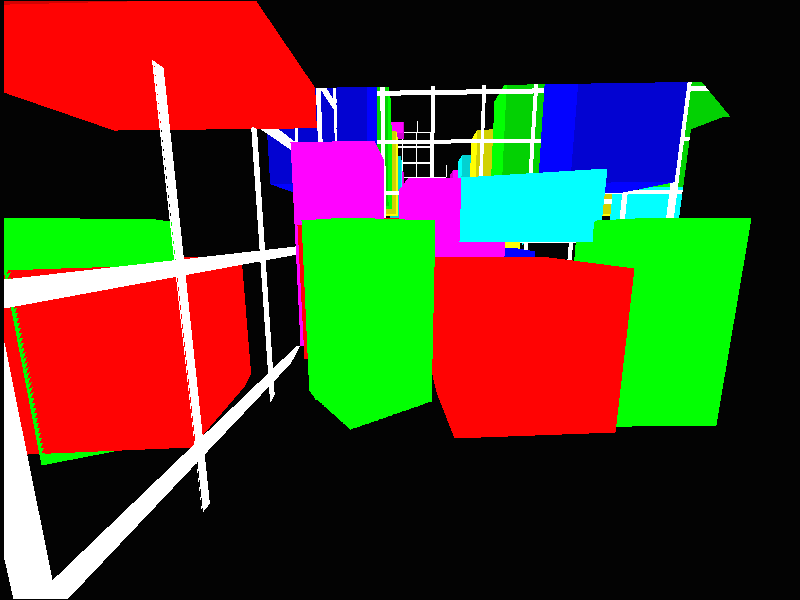

Consider the radical formal avant-garde, which Schrank classifies as subverting the mainstream approach to flow as the brass ring of game design. Slipgate, a level in Untitled Game by Jodi, is a mod of first-person shooter Quake that alters the player’s sense of virtual space in unexpected ways. In Slipgate, gridded walls and solid geometric shapes litter a black void space that you edge your way through. However, the visual geometry of the level does not match the actual navigable space, meaning there are invisible obstructions and some of the objects you can see can be walked through as if you were a ghost. There is no flow state in Slipgate, no opportunity to get “in the zone.” The game is meant to be frustrating, but also to enlighten players to the architecture of game design. As a “game,” Slipgate is broken, but seeing it for the radical formal avant-garde game that it is, Slipgate works as designed, just not in service of flow.

Schrank doesn’t spend much time in Avant-garde Videogames talking about traditional, popular games, except to reference them as the status quo, a constant by which we can measure how far afield the avant-garde can reach. He quotes iconic mid-century art critic Clement Greenberg is labeling mainstream games as “kitsch”—that is to say “easily consumable media.” Kitsch games manipulate emotions based on tried and true formulas. They’re complicit formal games without the avant-garde daring. In contrast, the diversity of avant-garde games makes them more difficult to approach as a whole entity, proving the approach of a text like Schrank’s to be a valuable asset.

I found it most useful to read Avant-Garde Videogames as a work of art history and theory. The book doesn’t frame its subjects in chronological order or offer a timelined history of avant-garde games, but focuses instead on the thought-spaces wherein these games exist. It’s an interesting approach that says quite a bit about the current state of art—namely that all of the past art historical movements are actively in play in contemporary practice. Coupled with the fact that videogame history only goes back a matter of decades, it’s much more useful to draw comparisons to 20th century cultural movements than to show how one game idea came before and influenced another. Ultimately Schrank paints a picture of avant-garde videogames as holders of amoebic cultural status, soldiering on in their individual pursuits and leaving himself and other historians to debate what comes after Post-Modernism.

After all, in 2014 the hot-button theoretical debate has moved on from “can games be art?” to “what is a game?” Schrank addresses this question by turning the term “videogame” on its head. “Why not also examine the idea that videogames are videos?” he prompts (mind = blown). And really, that question embodies the spirit of both Schrank’s book and its subject matter, because for all the solid ground he lays out in Avant-garde Videogames, he asks just as many questions as he answers, which is by design. He sets up the paradigm of avant-garde videogames as an ever-expanding universe of concepts. Sure, Schrank has charted a few constellations for us here, but depending on vantage point, there will always be other arrangements of stars.

///

Header image via John Lester

Double-exposure image via Doctor Popular