From the monochrome wireframes of Asteroids to the virtual-reality galaxies of Elite: Dangerous, technology and videogame genres improve at a frantic, thrilling rate. However, some genres are more resistant to change than others. While certain seminal franchises of Japanese origin such as Street Fighter or Final Fantasy continue to grow their Western popularity and adapt to new styles of play, the side-scrolling shooter genre danmaku (??, literally “bullet curtain” or “curtain fire”) remains stubbornly niche, even anachronistic. It’s a cultural legacy especially untapped in the West, but Jamestown+ and its creator Mike Ambrogi Primo aim to change that.

The game, which was recently released on PS4 and Steam, owes its existence to Eastern classics, but it’s not interested in emulation. “It’s one of gaming’s great ironies: that one of the most accessible genres of all time, a genre defined by Space Invaders, has earned an iron-clad reputation for inaccessibility,” Primo told me. Though the genre’s arcade cabinets and console ports have stretched imaginations and reflexes across the world, he says, “at this point, shmups are a hard-line classicist’s genre, and outsiders tend to be driven away by intimidating waterfalls of intricate bullet patterns and problematic representations of teenage girls.”

Indeed, danmaku is decidedly hardcore, and rarely deviates from settings full of either spaceships, giant robots, or school-girls with occult superpowers. These are games defined by the “right” way to play not being merely to survive, but to rack up SS ranks through a combination of furious elegance, pattern recognition and an understanding of the games’ elaborate/baffling score multiplier systems. This means that navigating the hyper-colourful, meandering bullet spirals of the Dodonpachi series or the more furious pace and myriad weapon modes of Treasure’s Radiant Silvergun is as demanding a cerebral workout as it is for your fingers. The most us mere mortals can usually hope for is tackling a level with some small grace, which makes efforts such as this video, of someone perfecting Ikaruga (Radiant Silvergun’s spiritual successor) while controlling both ships himself, the ultimate expression of danmaku.

Despite initially deciding on a danmaku game due to “sheer pragmatism,” Primo quickly realized that despite a “limited set of player affordances” an authentic game in the genre would need to be rigorously technical. Whereas many modern shoot-em-ups will have subtly differing enemy placements and behavior for each player (often referred to as procedural generation), Eastern shoot-em-ups are hand-crafted affairs with thousands of deliberately-placed enemies and intricate, unique bullet patterns. “Every little enemy spawner has been carefully considered against the behaviour of several interrelated scoring systems.” Primo says, and admits that “I’ve never seen anyone from the West who can do it.” However, Primo’s goal wasn’t to play the masters at their own game, but to chase a “dream of true cooperative play.” Indeed, past danmaku and most Western shmups have featured two-player modes but in no meaningful, interdependent way. In this post-Left-4-Dead, post-Rock-Band world, Jamestown+ manages to bring a “more modern co-op design sensibility to the shooting game genre” through its use of a revival mechanic, as well as space for four simultaneous players.

One reason this may be the case is how rooted this mindset of fierce, beautiful precision is in Japanese culture. Take ikebana, the painstakingly precise Japanese art of flower arrangement, the garish pageantry of kabuki (dance-theatre) or the Bushido code (what we might call the “Samurai Way”), which was informed by Zen Buddhism. A state of Zen, or calm action, is something the intense concentration required to navigate danmaku often evokes. The aforementioned Ikaruga in fact makes this even more literal, the game’s main conceit being the Yin/Yang-esque polarity system wherein the player-ship can absorb bullets of the same colour and deal bonus damage to enemies of the opposite. An important tenet of Zen is “zazen,” or “just sitting,” something the player of Ikaruga is actually rewarded for, as when they complete a level without without firing a single shot, earning them a ‘bullet eater’ bonus accolade.

This is why, perhaps, the majority of Western shmups pin their hopes on procedurally-generated levels and offer a huge range of weapon variety, such as the forthcoming “bullet-hell dungeon crawler,” Enter the Gungeon, or the Borderlands series’ hyperbolic claims of a gazillion guns.

On this side of the world, it all goes back to Robotron 2084, one of, if not the most influential shmups. The 1980s game is responsible for coining the gameplay tropes of increasingly hard/dense waves of enemies, a fixed grid arena, and a control scheme based on two joysticks, one to control movement and the other to control directional fire. Robotron has inspired countless “twin-stick” shooters, but it wasn’t until the bizarre story and success of a minigame playable from the virtual garage of Project Gotham Racing 2 named Geometry Wars that the sub-genre exploded into modernity. Since then, there have been a raft of imitations, perhaps most prominently Housemarque’s Super Stardust and Resogun.

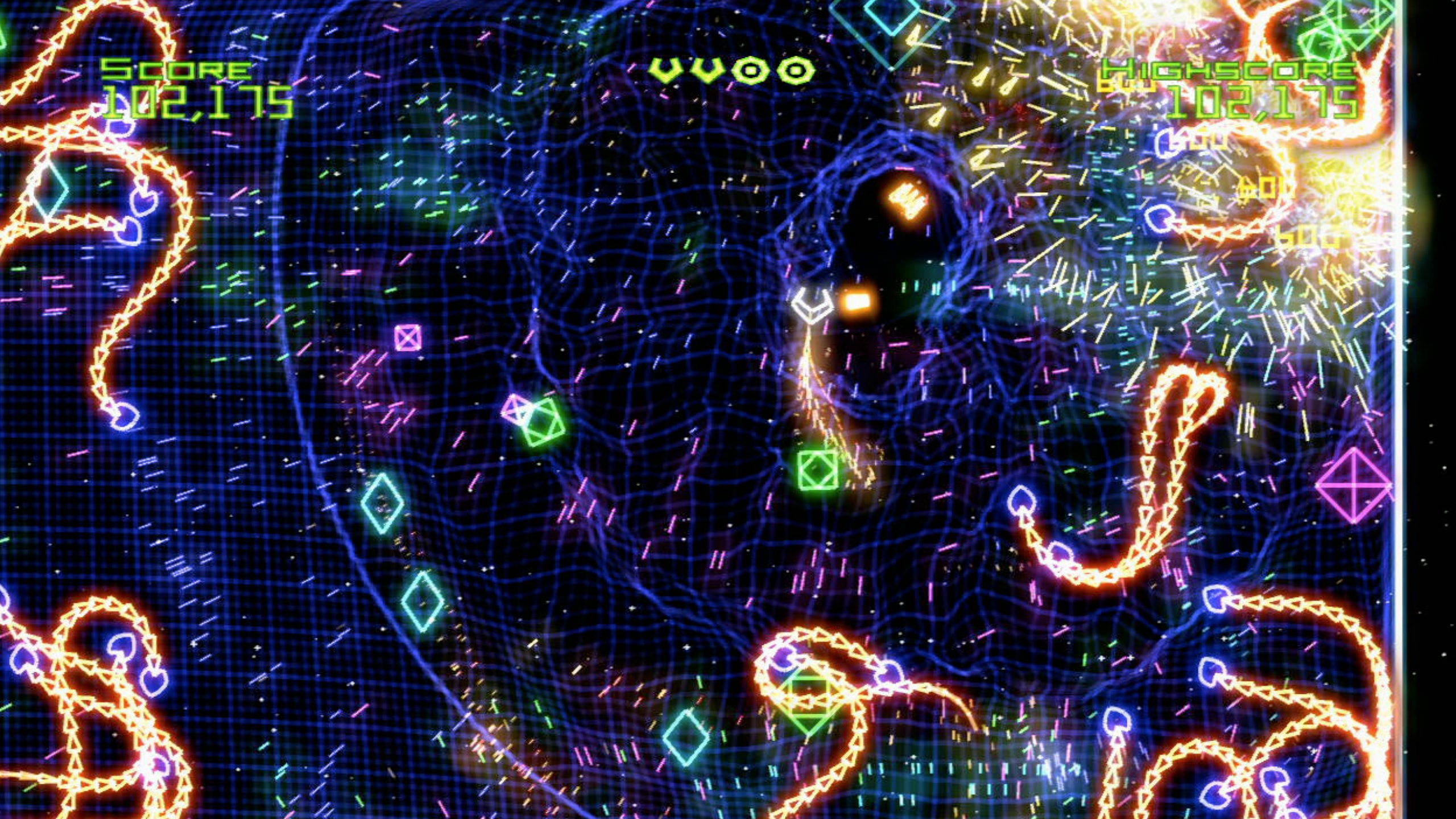

The in-development Zenzizenzic blends twin-stick action with the abstract style of Geometry Wars and the dance & riposte elegance of danmaku. If anything it’s even more abstract than Geometry Wars, with bold, graphic 2D visuals and, in the main mode, a static play area. According to designer Ruud Koorevaar, “Zenzizenzic refers to the square of a square, or 4th power. It’s also a play on the Buddhistic ‘zen,’ as the game is quite intense.” What really marks the game is a mode that breaks the confines of a scrolling level, and allows players to roam randomly generated levels at will, encountering enemies and earning new abilities as they go. Koorevaar continues to tweak and improve the mode through regular updates, but even the current state suggests the blend of abstract exploration, minimal electro and bullet-hell action could hail an interesting new step.

It’s tweaks to the formula like these that might open the doors to a wider Western audience, although so doing risks alienating the die-hard old-schoolers. After all, it’s easy to look back with glasses tinted by the rosy afterglow of a frame-rate hobbling explosion, but danmaku deserves more. “They may be the granddaddy of all videogame genres,” Primo says, but as their mass appeal and sales waned in the early 2000s most danmaku releases became downloadable ports for Xbox Live Arcade or Steam. The developers who kept the signal fires lit increasingly did so for a heavily “masochistic sub-niche,” according to Primo, who compares the audience to those “Japanese soldiers who holed up on obscure Pacific islands for decades, completely unaware that WWII was long over.” Now, western developers like Primo and Koorevaar, along with the even more accessible hybrids such as Resogun and Enter The Gungeon, are starting down a new path, while retaining the purity of expression of the danmaku of their youth. Like a musical genre that continues to mutate and adapt, resurfacing time and again, danmaku has proven uniquely resilient.

///

Note: An earlier version of this article misstated the correlation between bushido, Taoism and Zen. It has been updated.