This article is part of Film Week, Kill Screen’s week-long meditation on the intersection between film and videogames. Check out the other articles here. And, if you’re in NYC, grab tickets to our Film Fest at Two5Six on Friday, May 15th.

////

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a game studio in possession of popular franchises must be in want of new markets for its popular franchises. And so was born the most universally derided genre in contemporary film: the videogame adaptation, an unhappy marriage of game companies attempting to leverage successful brands with uncreative Hollywood studios in need of fresh source material. To date, not a single videogame adaptation has managed to crack 50% on Rotten Tomatoes (at present, Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within ranks “highest,” with 44% approval).

But what, exactly, made these movies so reviled? Has it simply been a long string of particularly incompetent writers and directors? Or is there some deeper tension between games and film that prevents the “successful” importation of the former into the latter? Like mass-market games, popular film is as much as product of the boardroom as it is the writer’s desk. Alone a purely artistic or economic explanation isn’t enough to explain the game adaptation’s profound shittiness, but, taken together, they can illuminate why an entire genre of film—to be clear, movies directly based on specific videogames—was dead on arrival.

Though the first wave of videogame adaptations was produced in the early 1990s, videogames were an occasional topic for film in the 1980s. In Tron, WarGames, and The Wizard, for example, videogames offered a means of examining cultural anxieties over digitalization, thermonuclear war, and youthful obsession. Yet it wasn’t until 1993 that film also began to treat games as source material, largely as the result of the convergence of a number of trends in gaming and Hollywood that allowed the two industries’ interests to align.

Depending on whether foreign film and anime are taken into account, the first major videogame adaptation was 1993’s Super Mario Bros., the result of a transpacific comedy of errors that led to one of Hollywood’s biggest errors of comedy. Within a year, it was joined by Street Fighter, Double Dragon, and Mortal Kombat in American markets, as well as a handful of animation flicks and made-for-TV specials. In Hollywood at least, videogames were finally getting their 15 minutes of fame.

The chronological proximity of these films is striking, as is their common source material: fighting game franchises. In its economic context, however, the emphasis on fighting games as workable content for blockbuster film helps explain why 1994 saw so many film adaptations of videogames.

Though the 1980s were a turbulent decade for the game industry, it had largely recovered by 1990, thanks to a new generation of home consoles. At the same time, the popularity of gaming at home meant fewer people were going to arcades, which saw their revenues drop precipitously in the final years of the 1980s. The 1991 release of Capcom’s Street Fighter II, however, offered a momentary respite from the arcade’s multi-decade decline and fall. SFII revolutionized the fighting game genre and singlehandedly ushered in a renaissance at the arcade. Other game studios rushed to update their own franchises or establish new ones to leverage the surge of interest in fighting games.

At the same time, Hollywood executives had become convinced that audiences were interested in high-budget action movies that featured novel computer generated imagery, stylized violence, and intricate fight and chase sequences. Following the success of Die Hard, major studios were in the market for new action franchises. In videogames, they found what seemed to be ideal source material, heavy on action, violence, and CGI. Best of all, videogame studios were equally interested in capitalizing on the fighting game’s rejuvenation of the arcade.

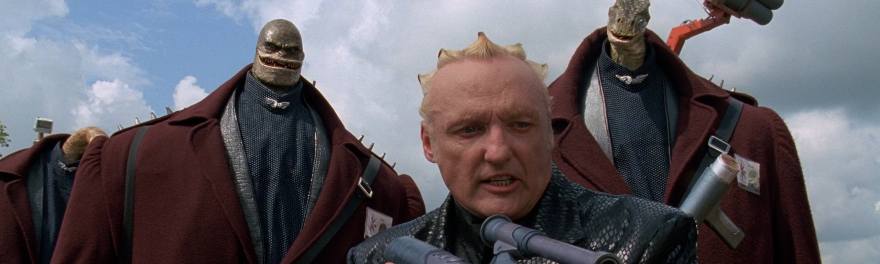

Street Fighter, released in American theaters in December 1994 by Universal Pictures, is a typical product of this unhappy collaboration. Anchored by action star Jean-Claude Van Damme, Street Fighter II extrapolated what little character there was in the arcade version to generate a narrative that pitted popular characters (Ryu, Ken, Vega, etc.) against a rogue general, M. Bison, the game’s primary antagonist in the fictional nation of Shadaloo City. A warren of action clichés, Street Fighter’s plot manages to be both familiar and incomprehensible, and the many one-liners that precede fisticuffs are to humor what Robert Mugabe was to democracy.

Yet plot and cliché alone makes Street Fighter no more incompetent than any unremarkably bad action movie (of which the 1990s had many). And while economics helps account for the movie’s existence and its general badness, it doesn’t touch on the fundamental issue that ailed Street Fighter, or, for that matter, virtually every videogame adaptation of the era: the uncomfortable joining of two distinct media, each with its own conventions.

Street Fighter’s final scene is emblematic of the clash of conventions: a defeated General Bison is resuscitated by a previously unmentioned, solar-powered “revival system” (who knew he was so eco-conscious?). Innervated, he smashes his fist through some rubble and selects “World Domination: Replay!” on a nearby computer, a reference to Street Fighter II’s “replay” screen.

What binds videogame adaptations together is the continuing and largely unsuccessful attempt to balance faithful references to their source material (characters screaming “game over,” boss battles, etc.) and the conventions of the 1990s action movie. Street Fighter’s director, Steven de Souza, stated that he removed all the supernatural elements of Street Fighter II to give his adaptation a more “realistic” feeling that would appeal to viewers who hadn’t played Street Fighter II. Paul W.S. Anderson, director of the more mystical Mortal Kombat, was less burdened by a need for realism, but was equally caught up in a common narrative device in videogame adaptations: a plot that exists solely to carry the viewer from fight to fight, much like these movies’ namesakes.

The inability to clearly distinguish between the conventions of two forms of media helps explain why videogame adaptations have been crimes against the arts. The art theorist Gotthold Ephraim Lessing famously held in the 1766 text The Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry that the “confusion” of individual arts would only lead to aesthetic disaster. Lessing imagined that individual media were akin to sovereign nations with definite borders; artists working in one medium would do well to respect its boundaries. The art critic Clement Greenberg took up this cause two hundred years later, when he declared that media “mature” by shedding the conventions of other media.

With respect to videogame adaptations, it’s hard not to admit that Lessing and Greenberg might have a point. When puzzled critics were faced with an onslaught of game adaptations in 1994 and 1995, many commented that the films did little more than offer a live-action simulation of a videogame’s rhythms and narrative architecture. Games are often characterized by the way that they prolong time, forcing the player to fight wave after wave of enemies before incrementally advancing the plot. Popular film, in some ways, performs the inverse via the cut: plots that take place over months, even years, can be reduced into a manageable two-hour sitting. No wonder the juxtaposition of the two was unflattering to both: what little plot exists in Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat feels caught between its source material’s convention of extending fights for the player’s sake and action film’s need to compress time for the viewer’s attention.

Is this doom written in the nature of the adaptation? No more than cinematic adaptations of novels, or, for that matter, painterly renderings of poetry. In a less famous passage of The Laocoon, Lessing noted that even if painting and poetry (or videogames and film), they will inevitably make incursions into each other’s territory, most for ill but some for good. The challenge, then and now, is matching content to form: Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat were not doomed because their sources were unfilmable, but because their directors tried to make movies like they were games. When eventually adaptations take content and not form as source, videogame adaptations might have a chance at success. At this moment, over two dozen movies are in the works, including story-rich franchises like Mass Effect, WarCraft, and The Last of Us. Whether or not they’ll be successful movies is an open question. That they can be is not.

////

This article is part of Film Week, Kill Screen’s week-long meditation on the intersection between film and videogames. Check out the other articles here. And, if you’re in NYC, grab tickets to our Film Fest at Two5Six on Friday, May 15th.