This review was originally published on September 23, 2013.

///

It’s safe to say that Phil Collins is one of the most important people in the world to me, and that I love him in the truest way possible: without any demand for reciprocity. He’s always helped out in the singular fashion only your favorite musician can. In the video for “I Don’t Care Anymore,” Phil stands against a soft black drop and cries out righteously:

I don’t care what you say

I never did believe you much, anyway

So get out of my way—let me by

I’ve got better things to do with my time

I don’t care anymore!

When Michael De Santa, one of the three protagonists of Grand Theft Auto V, puts in his earbuds, lies down in the sun, and flips on this song, the drums starting up in my ears as he lights a cigar, I have to laugh. I have done exactly this, sans cigar, sometimes every day for months.

I shudder with recognition, here, as in so many other places, at the bleeding edge of reality in Grand Theft Auto V. I am both delighted and disturbed by how much I see elements of myself, and of everyone I know, in the narratives of the three protagonists: Michael, Franklin Clinton and Trevor Philips.

That statement doesn’t look too good, for my health or for those I know, does it? You can put the phone down. Let me explain.

I’ve been playing a big man with an oversized gun in video games since I was a little girl, ten years old and secretly installing Doom on my Gateway when my parents were out of the house. I have always played at manhood in games.

There has been a laser focus on the lack of playable women in GTAV, what that lack means, why it means what it means, and plenty of debate over whether it should mean anything.

I have always felt strongly that there are countless joys in playing the other gender as an exercise in empathy. In fiction, the truest standard for the creator is whether the character is believable, not whether he is good or deep or even particularly subtle. I believe in a Raskolnikov or Lou Ford, morally reprehensible characters, because the best fiction paints the worst qualities a person can have and still invites you in to empathize.

The question of why we need ideals that reflect ourselves back to us, and why we seem to need our representations in games to be ideal, is fascinating. But the imperative for a diversely represented world where men and women are equally powerful, having subtle conversations and offered a vast range of interesting moral choices, is itself a type of bind. Art has zero obligation to serve as an ideal or to represent the world in an ideal way. To place any imperatives on a fictional world to be anything other than the creator’s vision compromises and chokes out its purpose. A piece of work needs to be judged based on the rules it establishes.

After six days and over fifty hours, having finished every section of every mission and explored as much of this world as I can, I am emotionally drained. I can’t talk about how the men in GTAV are punished and rewarded, and how much I feel for them, quite yet. And I won’t talk about the series as an indictment of the American Dream or capitalism; as long-running platform for contentious portrayals of women and minorities; as geopolitical space; as revolutionary masterpiece of interactive design; as related to Deleuze; as ethnographic folklore; as neoliberal fantasy of male power, or as an exploration of what gangster culture means for America’s identity.

Others will do this. (Seriously: search through an academic database. There are thousands of monographs on the GTA series.) And besides, there are other questions to explore: Why do I enjoy playing as these men? Why do I understand them? Why is violence their only option? Why does chaos feel beautiful and true to me over the course of my play? How does this world get me to believe that what I am doing is just the way it is? How do I better understand where violence takes root; why does it feel meaningful and intentional, rather than mindless and pointless?

///

Grand Theft Auto V is, at its core, a game about the most suffocating ideas of masculinity and what a man should aspire to be. It tells us how men, and women, must shape their lives against, in accordance with, outside or in reaction to these ideas. The world, both in-game and in real life, ruthlessly punishes men who step outside that story of power and domination. Michael, Franklin and Trevor each fall at different points on the spectrum of acceptable manhood.

Of the three men we play, Michael De Santa is the most vivid and believable. The ruin of his body shows in the many lines around his eyes, which glint intelligently and sharply from a rough, angled face. Formerly Michael Townley, this self-described “washed-up jock” lives under witness protection, in a stunning house in Rockford Hills. Loaded with bad memories, mistakes and regret, Michael drinks to forget. “I done a lot of things I ain’t proud of,” Michael tells others, too frequently. “You seem like a man who is into nostalgia,” Franklin mumbles to Michael over the phone.

His family openly despises him, and they punish him continually for how he has failed them as a father and husband. His wife, Amanda, is always angry; she is also boning the tennis instructor. His two children, Jimmy and Tracey, are useless. Jimmy gets high and diddles himself in his room while playing Righteous Slaughter 7 and has never worked a job. Tracey is obsessed with reality television and fame; she tries to get there by grinding up on a seedy producer aboard a yacht, the DIGNITY LOS SANTOS. Just a normal American family of so many, each unhappy in its own way.

The second man is Franklin, African-American, gang banger, living with his aunt. He is restrained and taciturn, bridging each new struggle with relative calm. His friend Lamar, with “that Apache blood,” is all talk about balling, being a big dog, that paper, and knowing these streets. They do odd repo jobs for an Armenian car salesman or they drive a tow truck. They drive in circles, constantly hustling.

The third man is Trevor, living the scummiest of scummy lifestyles with no apology in Sandy Shores (Motto: “We Have Liquor”), a wasteland of trailer parks, meth labs and ATVs. He is psychotic and trashy, and players seem to adore him. Some of his rants about the government and society hint at the Judge in Blood Meridian, paeans to taking what you can in this world, to defining your own moral compass: all the terrifying logic of a master killer.

I believe in all these men, and in their supporting cast, because the world we drive through is mad, and Los Santos is the condensed carnival of this madness, and so the alienation and dysfunction of all these men aren’t really that far from possibility. Take Lester Crest, a data mastermind in Dahmer-esque glasses, gathering the logistics the gang needs to pull off their heists. We all know some mild version of this nut-job, talking about assaults on our freedom and what really happened on 9/11. Take that paranoia and delusion to its utmost end, and that man is Lester, living in a house in the bluffs heavily guarded by surveillance cameras, labeling boxes of papers Hoaxes and Assassinations.

There is a whole refugee camp of men—like Lester, like conspiracy theorist Nervous Ron—living in the liminal space between acceptability and exile, men who can’t hold it together, who can’t buy in, who can’t believe in the great lie of the American Dream. “We’ve been lied to!” they all yowl, separately and in their own way. Their frustrations and impotence form a cloud, a hazy funk around them. Someone, they all seem to say, someone out there has to pay for the state my life is in.

///

The hyper-reality of this visual world, the fidelity to mood, atmosphere, sound, light, is staggering: like a razor held against the eye and ear and mind. I could rhapsodize all day about the world’s details, from the lines in the dust an airplane makes as it turns onto a makeshift runway, to the sound of waves crashing against the rocks of the bay, to the stars revealing themselves just as you drive out of the city limits, to the feel of wind and rain against the jagged hills. Each of the distinct neighborhoods of the real Los Angeles with their peculiar colors and dialect. The sun sparking off the blades of windmills, studding the fields in neat lines. A car’s light turning on each time you open the door.

This deep replication has a meditative effect. Many times, I find myself lost, truly and wholly lost. Riding in GTAV—whether in a car or on an ATV or an ocean cruiser—is hypnotic and soothing. At several points, I have, as happens in the best games, veered off track, off road, to explore, read signs, hear strangers’ conversation, to soar out into the desert alone. After cruising for ten or fifteen minutes, taking in the mountains, the smooth and clean road, I find myself meditating again, about my own life. It’s at this point that unease and anxiety build in my chest.

“Life isn’t meaningless. You’re deeply troubled, but together we can make you a functioning member of society,” Dr. Friedlander, Michael’s therapist, says as he checks his watch. In one of the earliest cut scenes of the game, Michael starts to have an epiphany during therapy: “I am having a breakthrough. What it comes down to, is, I’m terrified that—” and here, right here, he is cut off, perfectly. The hour is up. He can come back next week. Just as he is about to get some insight, he is forced to turn away.

There’s no true safe space for a man like Michael to get to connect or reflect. He is 45 years old, fumbling with the same issues he wrestled with when he was 20, a fact he will lament up to the game’s close. He’s done more bad than good and he has never really changed.

“Is it the place or the time? Is it Los Santos?” we hear over the phone. “Everyone I meet here is crazy.” This exact representation of Los Santos (Los Angeles), this “toytown run by psychopaths,” is well known. Films from Sunset Boulevard to Mulholland Drive have worked through the darkness and dirt seated under the city’s chrome exterior. Disappointment, restlessness and unhappiness persist in the most lavish places. If you talk to a person born and raised in the area, they will tell you about the pervasive anxiety and existential dread sewn into the sprawl, the gulf between the worlds of Watts and Echo Park, Venice Beach and Silver Lake. They will tell you how residents play up their personalities based on wherever in the city they try to take root, for a year, or for a lifetime. Shaking his fist at the city skyline from the hills, Trevor howls, “Los Santos! The city where the dead come back to life!”

During my first plane ride to Los Angeles, in real life, I was overwhelmed by the vision of the vast patchwork of thick orange veins below during landing. The city’s promise felt so great that I disembarked, tore open my laptop in the airport lounge and wrote, Everything feels possible here. In GTAV, whether you are in a helicopter or careening softly down in a parachute, seeing the city below you in just this way has the same effect. But paired with this hope for freedom and potential is fear.

“Getting the fear” is a symptom of using bad drugs, a unique blend of paranoia, confusion, and abstract terror. You get that specific fear playing a couple of side-missions involving a pro-marijuana evangelist, hallucinating an army of Predator-aliens and clowns. But I got the fear just living through my Los Santos travels; I also got the anxiety and the dread. The fear, though, was never of my many adversaries—the FIB, the IAA, Merryweather Security, or any of the dangers accompanying the escalating arc of more and more complex heists. Dealing with them felt nearly manageable, easy and clean.

“My fucking life is fucking fucked,” Michael spits at Friedlander, reflecting on his rash decision to pull a cliffside house off its stilts with a truck. The cosmos of this game says “It’s not easy to be a man,” whether a normal law-abiding one or a paid killer. It isn’t easy being a human, period.

Men aren’t truly free in GTAV. They are bound in different ways from women, held to different rigid standards and equally impossible expectations. Playing GTA: San Andreas, I was always struck by the peanut gallery of insults that reinforced these rules. CJ was mercilessly shamed by his friends to step in line (Get a haircut and some colors; it’s embarrassing to be seen with you). Here, ten years after that title, Michael is shamed for all his failures. His wife reminds him he is a failure and hypocrite at every turn; Trevor shames him for selling out; his children shame him for being dysfunctional; even kooky Ron shames him for his success.

No one can be bothered to help him, of course. He is a man; he should be able to figure out his issues, fix things. In much the same way, Franklin is shamed by Lamar for his inability to roll hard enough, and by his aunt for his perceived disloyalty. Trevor may be the only one to largely eschew shame or guilt, but his rejection of both is its own trap—his self-isolation on the desert fringe, his put-on bluster and performance of brutality.

Even as I see Michael, Trevor and Franklin spinning in their hamster wheels, their attempts at being hard play as humor. At one point, Trevor, in a stained bowling shirt, his tuft of stringy hair sprouting from his greasy bald dome, rumbles along on an ATV to Robyn’s “With Every Heartbeat.” Michael tries out a yoga session with his wife and takes their very French yogi’s insistence he align his “mouth with anoos” in perfect stride, poker-faced.

Even as GTAV lets you release through laughter, it breathlessly reminds you, at every turn, of the way these men are bound up in rigid roles. In one heist, the men are given masks to pick from. There are wrestling and hockey masks, heads of apes, pigs and monsters, and, of course, skulls. These masks are their only choices. Who knows if they want to wear a different kind of mask? Who would even care?

///

There’s very little love, tenderness or affection in GTAV, save in one space: male friendship. Who is there for Michael when life gets messy and hard? Trevor is there. Franklin is there. I felt part of their camaraderie; I bonded with Michael and Franklin, even Trevor; I understood and believed in the aggressive friendships they forged.

The three are usually arguing bitterly with one another, leveling each other with scorched-earth intensity. This is how these men bond, through jokes, frustration, rage, reactivity and brute force (which also happens to be the name of a game within the game). The rich, sharp banter, the ribbing, and the harsh insults hide growing affection between them. Listening to them snap and snarl, I see how they are trying to connect and cope. Michael clearly empathizes and cares for Franklin as a son, calling him a good kid. Franklin tells Trevor that he is clearly batshit, but sure, he likes him. Trevor indulges Michael’s sheepish love for old films, and goes with him to watch a movie downtown, though he sleeps through most of it.

In a world where everything is replaceable, the only source of significant, stable meaning seems to be the relationships that Michael, Trevor and Franklin create with one another. I wrecked my gorgeous vintage Declasse, but no matter, I’ll get a better car. I smashed my private jet into Mt. Chiliad, but it really isn’t a problem. I have everything and know the value of nothing, but I do have the names of two men who can laugh at these facts in the face with me, right in my phone.

These men do try to connect with others, even though they fail, and fail often. They each make gestures towards connection outside their tiny circle, towards some true bonding past acrimony. Michael wants a relationship with his son and forces him to connect through bike rides and tennis. Franklin wants to help his aunt and struggling friends out, but he is quickly swept up in the good life and is soon stuck in a beautiful house without anyone, just like Michael. He is a big man, but when he curls up alone on his new bed he looks, for a moment, small. Even Trevor has feelings (for a lawyer named Patricia), feelings he struggles to express in a text message to Michael with crude, territorial garble.

They are clearly aware of how they fail, because they talk about their failures to each other constantly. They know that they fail to be full, to realize their potential, to be reflective. They know that they ruin their own lives.

This inability to look at one’s failures directly is transformed into violence. For Michael, for Trevor, for Franklin, aggression is the only safe feeling, the only type of expression allowed, the only way to manifest their existence in the world. They are made whole to themselves through it. Eliminating is easier than feeling; destroying is simpler than daring to live. Getting right with themselves and having empathy would bring down the entire construction and artifice of their lives. They try, turn away, project, sublimate and create themselves through violence.

I understand this imperative, from the tiny ways we effect violence on those closest to us, to the big ways that implicate all of us. Think of our own world as the same “male power fantasy” shown in this game: our endless wars, our banks crashing, our government keeping neat files on us.

The reason GTAV felt novel and even hurt me a bit to play, is that I recognized these impulses in my own life and in the lives of all the people I know. I recognize this pattern: gesturing at that core space one yearns for, where people are good and true, backing down at the failure, and then turning away. I recognized the failure to connect and empathize. The high noon of one’s solitude, despite being buried in a pile of gadgets and phones and social websites. The hope to form relationships that aren’t eventually eroded by selfishness, weakness, boredom.

I flinch when Michael levels Trevor verbally, because I remember when I did the same to a friend. I remember the regret. I remember learning nothing and doing it again. In his therapy sessions, Michael talks about the Dream being ruined. Friedlander replies, “Let it all out. A sense of overriding futility is a vital part of the process. Embrace it.”

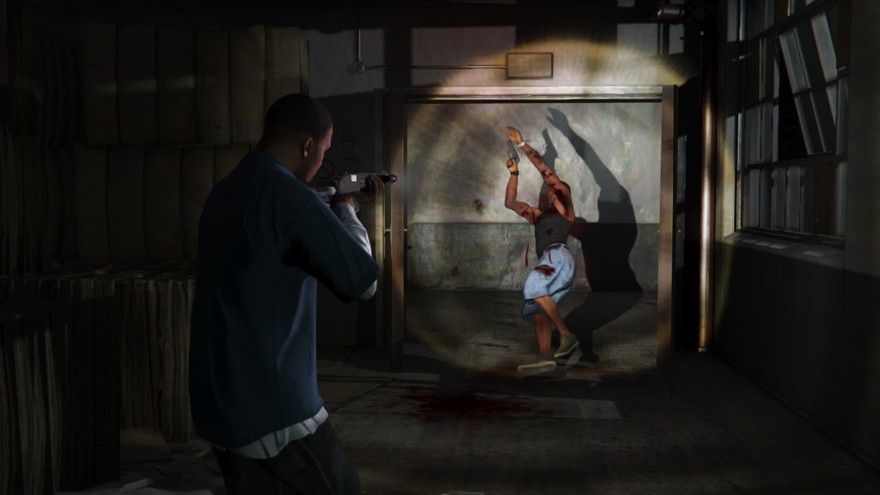

GTAV best illustrates the difficulty of self-reflection, of all the small ways we fail ourselves and others, each and every day. These men can only get lost in the passion fever of violence, the lull of avoidance, the embrace of a city that consumes them. That the game offers us this ouroboros from mouth to tail back to mouth again is, will always be, its great success. Michael puts his hands on an innocent body, then flings it roughly onto the highway concrete. Franklin looks right into a man’s eyes through his scope before sniping a bullet through his skull. Trevor stands before a man in a chair, then turns and chooses pliers over a wrench; he walks through all the rooms of a family home, then begins to empty a container of gasoline on his walk out.

Somewhere near the end of my playthrough, I’m in the desert as Michael, squinting grimly at the clouds and the sunset and the windmills, industrious and steady, churning. I grind along on my bike further out, to the satellite dishes all craned up towards the zenith. On the radio, Phil mutters, I’ve got better things to do with my time. I sweep circles around the dishes as they scan the heights above for signs of life, hoping for an alien abduction.