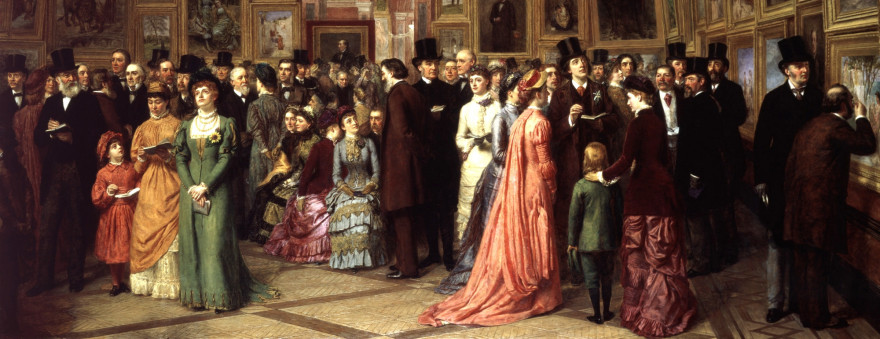

Header image by By William Powell Frith [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

//

At the ol’ day job I play Android: Netrunner at practically every lunch hour against a single opponent. Sadly, other office colleagues who might enjoy a hand or two of Hearts, Cribbage, or are even in our occasional office Pathfinder RPG session show absolutely zero interest in this game. They refer to it as “Click 5” and are halfway asleep in their soup before I can explain the eternal asymmetrical struggle between corporations and runners.

But maybe with Naomi Clark’s help, I can turn them around. Naomi is a vociferous thinker (twitter.com/metasynthie) and designer (deadpixel.co/about) who has been a part of the Brooklyn Games Ensemble and also done work in public advocacy. I first discovered her through Consentacle, a slick and sultry card game about human-alien intimacy and communication with elegant art by James Harvey. But it’s Lacerunner, Naomi’s 18th-century-society re-theme of Netrunner, that has me hoping that a few more players can be coaxed to the card table.

Instead of mega-corps using Intrusion Countermeasure Electronics (ICE) to keep runners out of their servers, Naomi is transforming Netrunner into a game about wealthy houses who use nobles to defend their various estates against riff-raff looking to disrupt the aristocrat’s schemes. The same mechanics apply to both versions of the game, a robust frame that is set up precisely to compare the cyclical nature of history in both near-future dystopia and not-so-distant-past class struggle.

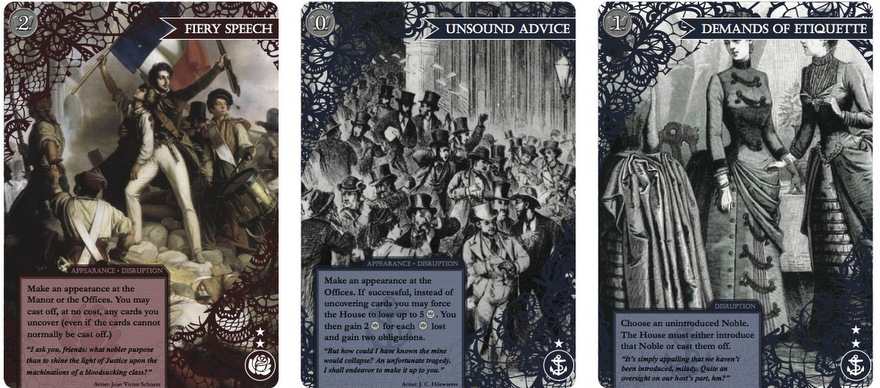

But it’s the artwork for Lacerunner that sells me, and hopefully a few of my cyberpunk-adverse friends. You can find a taste of it on Naomi’s site (http://deadpixel.co/lacerunner/Lacerunner-Cards-020514.pdf), and you should, because these are archival-sourced treats of paintings, prints, and old-timey advertisements that snap Lacerunner into a rich and specific historical era, as Netrunner does with its art and flavor text. Naomi is establishing a compelling and cohesive setting where each card fits into the worldview precisely.

What little information about Lacerunner that I could find has been so tantalizing that I decided to make a run at the source and ask Naomi a few questions via email. She had already been a fan of Netrunner, since many folks interested or involved in gaming have played a hand or two, so I asked about her take on the overall appeal of the game. As she describes it, the core of Netrunner is “a big complex system to wrap your head around, a whole set of strategic details to boast about and hash through with colleagues near and far on Twitter. It was the equivalent of the TV show everyone in an office is talking about at the water-cooler, but far more complex and widespread.”

For Naomi, it wasn’t simply the various potentialities of Netrunner that appealed to her, but also “the weird competitive intimacy in the asymmetric nature of the game—one player trying to read the plans and traps of her opponent in a much more tangible and immediate way than most strategy games (with what some people call ‘Yomi’) while the opponent is trying to undermine and anticipate every move.” This intimacy belies the narrative of Netrunner to a point, as the corporations are largely faceless and the runners use personalized programs and avatars. Each player, however, faces the other one on one, reading every twitch for some intel on their strategies; as Naomi says, it feels “like an intimate psychological dance.”

So if Netrunner is already so highly regarded, why mix it up? Most games blend flavor and mechanics, and even if a particular system is compelling, if the theme doesn’t grab you then that’s it, before the click is even fired. Navigating complex social hierarchies is something that drawing room dramas are well known for, so it was a short leap to Lacerunner, wherein Naomi plans to “re-theme the entire game—cards and descriptions and names of tokens and categories and everything—to portray a world based on a dystopia of history rather than a futuristic dystopia, the conflicts and pressures of social climbers and power elites in Edwardian and Victorian society rather than hackers and corporations, etc.”

More than just renaming the elements of Netrunner and digging up fantastic archival art, this “re-theme” is emphasizing some of the game’s fundamental properties: to subvert, manipulate, and exploit social structures. “The impersonality of jacking in, hacking, letting software act as a proxy-warrior for you while you slip into a backdoor—does all this serve to cool down the social intimacy between the corp player and the runner player? What if we heated it up and called attention to it instead?”

Lacerunner has the potential to reach many players who might otherwise be turned off by the whiff of “subroutines.” The goal is to strip away the AI and fiber optics and leave the raw back-and-forth between human beings at odds. This re-theme is akin to a mod, in line with the Skyrim texture mappers and passionate board and card game players who have been using house rules since the invention of the medium. However, Naomi has nothing but respect for Fantasy Flight Games, the publishers of Netrunner. “I don’t want to step on Fantasy Flight Games’ toes too rudely since I think Netrunner is fantastic—especially the rules and dynamics of play, which Lacerunner naturally shares, but also the qualities they clearly care about in building a world.”

Part of building that world is opening up the doors to all who might enjoy the experience. People like what they like, and it’s no fault of FFG’s that some aren’t drawn to the cyberpunk archetype. But with Lacerunner there is hope that they may be swayed:

“I’ve shown the Lacerunner cards to quite a few friends who I know are skeptical of really geeky games—the kind of folks who’ll go to see Lord of the Rings in theaters or watch old Star Trek: the Next Generation marathons, but steer clear of comicbooks, nerd-culture conventions, and unfamiliar boardgames with 15-page rule booklets. They’ve all been extremely excited by the artwork and flavor text, and the basic concept of ‘a game of 19th century social intrigue.’ I have no idea how much they’d tolerate the intense process of learning how to play the game and grasping how to use all the basic cards, but I plan to try and find out.”

What little can be found of Naomi’s cards so far are very exciting, especially as they feel both intimately familiar and fresh. The 17th and 18th Century aesthetic is locked in, based historical events and archival images, expanding on the already strong work FFG does to keep their game multi-cultural and gender inclusive, as well as avoiding a strict dichotomous reading of good vs. evil. No corp or runner is all demon or angel. Naomi wants to push this idea even further: “This is why I made the corp side in Lacerunner into a wealthy House that’s represented by a particular person, not just a faceless entity, and that’s why programs are social maneuvers, ICE are obnoxious guests at a party, and so forth.”

To facilitate these expanded personalities, Lacerunner may include a slight rule addition for the endgame that Naomi has yet to publicly reveal, one which she hopes that would encourage more role-playing within the game. “Not just in an ‘acting Victorian’ way but also in terms of feeling a little like their character is ‘closer to the action’—that’s part of the point of the ‘doubling-down’ on social intimacy.”

Forget not the humble runner though. The Shaper, Anarch, and Criminal factions depicted in Netrunner are built on solid historical models, but it’s telling just how succinctly Naomi has been able to incorporate them into her Victorian vision. “The Bourgeoisie are classic opportunistic social climbers, taking whatever advantage and profit they can find; the Bohemians are building their own social structure, but still seeking patronage and influence; the Revolutionaries are trying to undermine and upend the social order. It turns out, voila! These map exceedingly well over the three existing factions, each of which have their own flaws in one way or another.”

Naomi also wants to open up the dialog on that era of history, something that Victorian-tinged steampunk culture doesn’t always comment on: “The 19th century was a horror-show of colonialism and European empires running rampant, so I’d like to be able to evince that historical dystopia, without rose-colored romanticism, as much as anything else.” I can already taste the possibilities of getting my more literary and historian friends into playing Lacerunner, people attuned to every nip of subterfuge already found in the source material who have more interest in Jane Austen or Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy than Neuromancer.

Unfortunately, as Naomi describes, this re-theme is “a project that I’m not aiming to ‘finish’ and release on any firm timeline; it’s a labor of love and a hobby compared to other games I work on and design.” If it only ever exists as a thought experiment, Lacerunner is still quite compelling. Naomi has even considered it as something to exhibit “somewhere that people can play it for a limited time; although that’s not as convenient as the usual game-as-product model.” This makes sense, Lacerunner aspires to be a spectacle. Naomi is hacking in the historical strife between classes to life, and Netrunner is the stage; sturdy, well-built, and no stranger to the drama of interpersonal strife.