“So we do have … the ability and the right to control advertising by our licensees and we take that seriously.”

-Howard Lincoln, former executive vice president of Nintendo of America, at the 1993 Senate hearings on videogame violence

In the 1990s, in order to bear the proud Nintendo seal of quality, videogames went through a rigorous inspection that wiped away most religious, sexual, or violent content. Cross grave markers transformed into plain tombstones, classic Greek statues covered their bare bosom, and red blood became white sweat. This content control was even stronger when it came to their official merchandise and related media. The few Nintendo toys released in America were simple recreations of videogame characters and actions; little plastic bits made for kids to mimic their favorite digital moments. Television adaptations were just as safe: goofy cartoons that featured Mario and his costars in weekly escapades that were fun, colorful, and harmless. But through a licensing deal in 1990, Valiant Comics released a series of Game Boy stories that hardly fit Nintendo’s squeaky clean standards.

Dubbed the Nintendo Comics System, Valiant’s licensed comics featured Nintendo’s intellectual properties in four major series. The Super Mario Brothers and Legend of Zelda comics were an amalgam of their videogame stories and afternoon television counterparts. The heroes and villains were placed in familiar situations (save the princess, defend the kingdom/treasure, stop the bad guy); hijinks ensued. The end of every issue returned the characters to their usual balance of potential threat and good prevailing over evil, normally with a hearty joke to close out the story.

Captain N: The Game Master was directly aped from the television series of the same name, where a teenage game player is zapped into a digital world and believed to be their savior from evil. Reluctant hero Kevin Keene brings his meta-narrative skills to Videoland, where all of the game worlds he has experienced are his new reality. But instead of transferring the harsher aspects of our real world to this digital plane, Kevin merely brings a teenager’s naivety and some gamer tricks to a cartoon kingdom in need of help.

It is the fourth comic series that stood out from its Saturday morning cartoon ilk. A sort of reverse from the Captain N stories, the Game Boy comics brought adorable videogame characters into contact with the threats and negativity of our world.

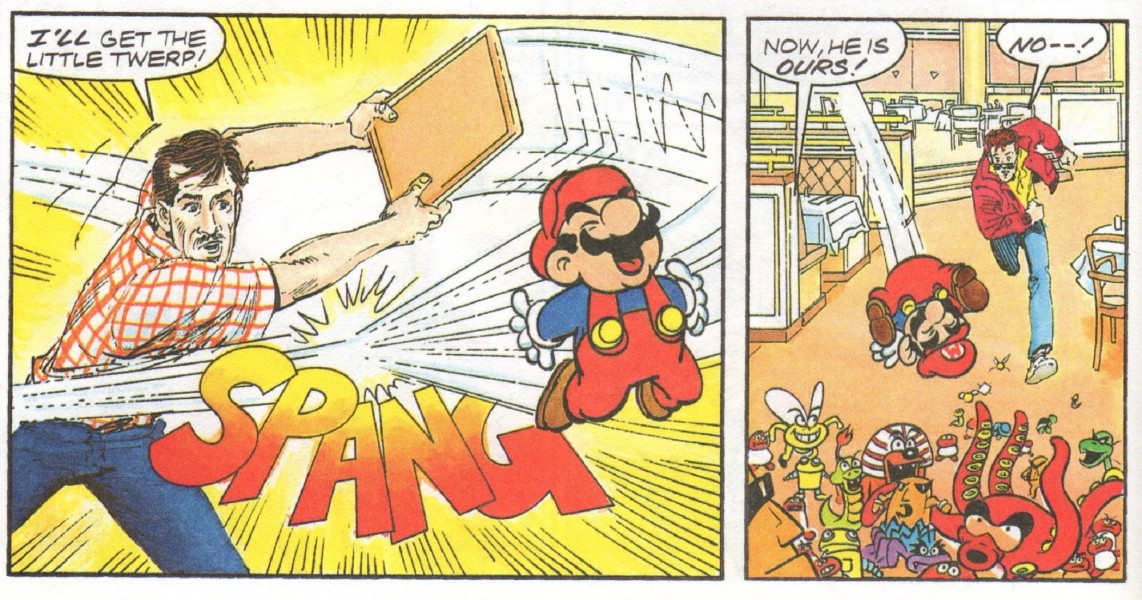

Even though the comics had a catch-all banner of Game Boy, the stories were exclusively based around a single game: Super Mario Land. At the time, this was the only adventure title on the handheld system, so it made sense to pull actual characters for a comic series instead of simple puzzle pieces. In the game, Mario was the hero of Sarasaland, tasked with saving the Princess Daisy from the mysterious spaceman Tatanga. The start of the comic series illustrates this story to the reader, making sure to emphasize that here in the Real World, these characters are merely images on a screen. Of course, it also indicates that, “this will change thanks to the power of Game Boy, in the palm of your hand!”

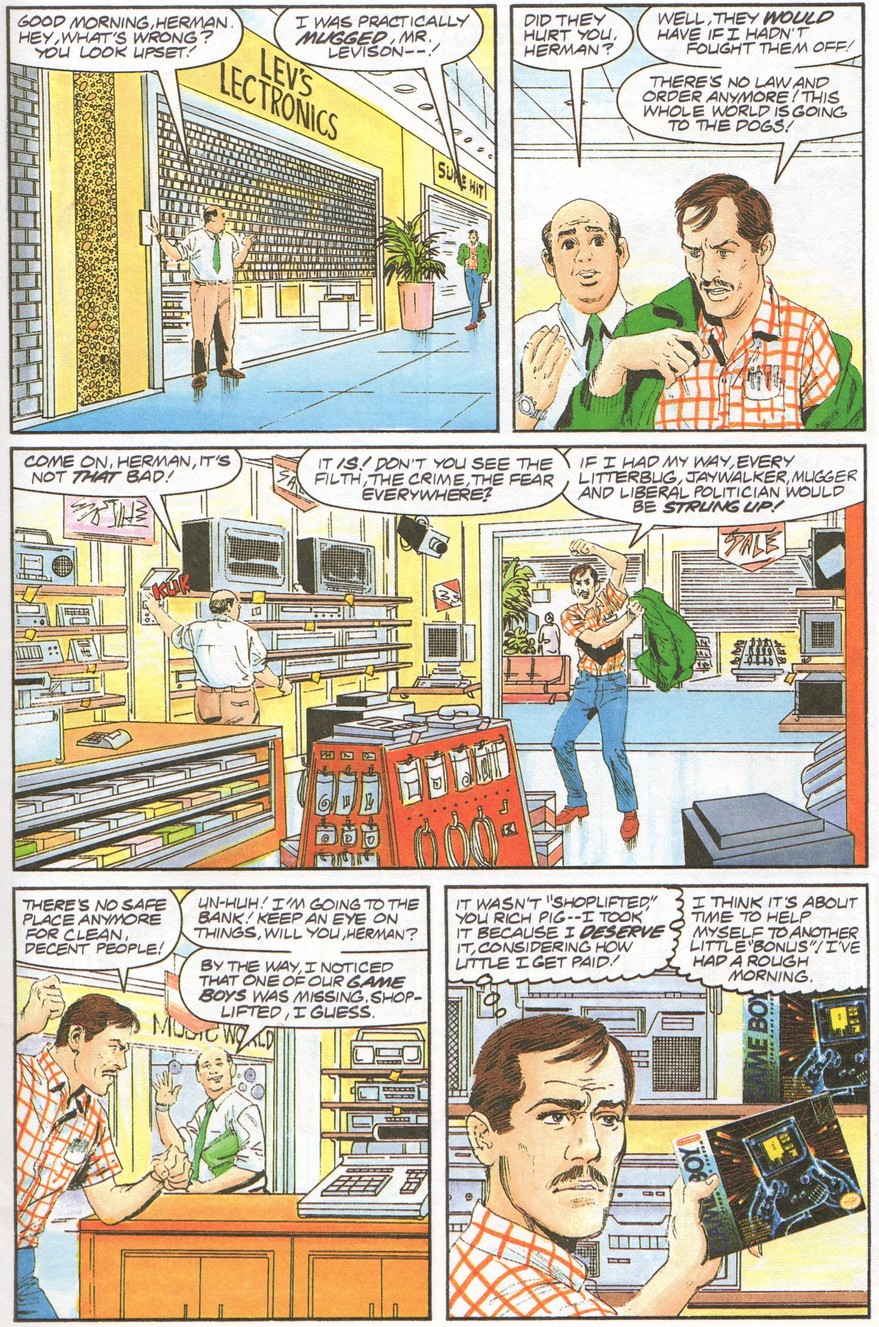

In the case of the Game Boy comics, the power lies in the hands of Herman Smirch. Unlike the other stories that open with beloved videogame characters or relatable teenagers, this story opens with a cynical middle-aged man who resides in New York. Herman lives in a tiny apartment, where his spare time is spent playing Game Boy and complaining about the state of the world to his pet hamster, Atilla. From the start, readers are not meant to like Mr. Smirch. He denies money to a beggar, shoplifts from his place of work, and, in perhaps the darkest mark on his soul of all, he purposefully kills Mario when he plays videogames. One day, while slacking off at work and claiming that, “every litterbug, jaywalker, mugger, and liberal politician should be strung up,” Herman finds himself at the mercy of a certain mysterious spaceman: that is, Tatanga.

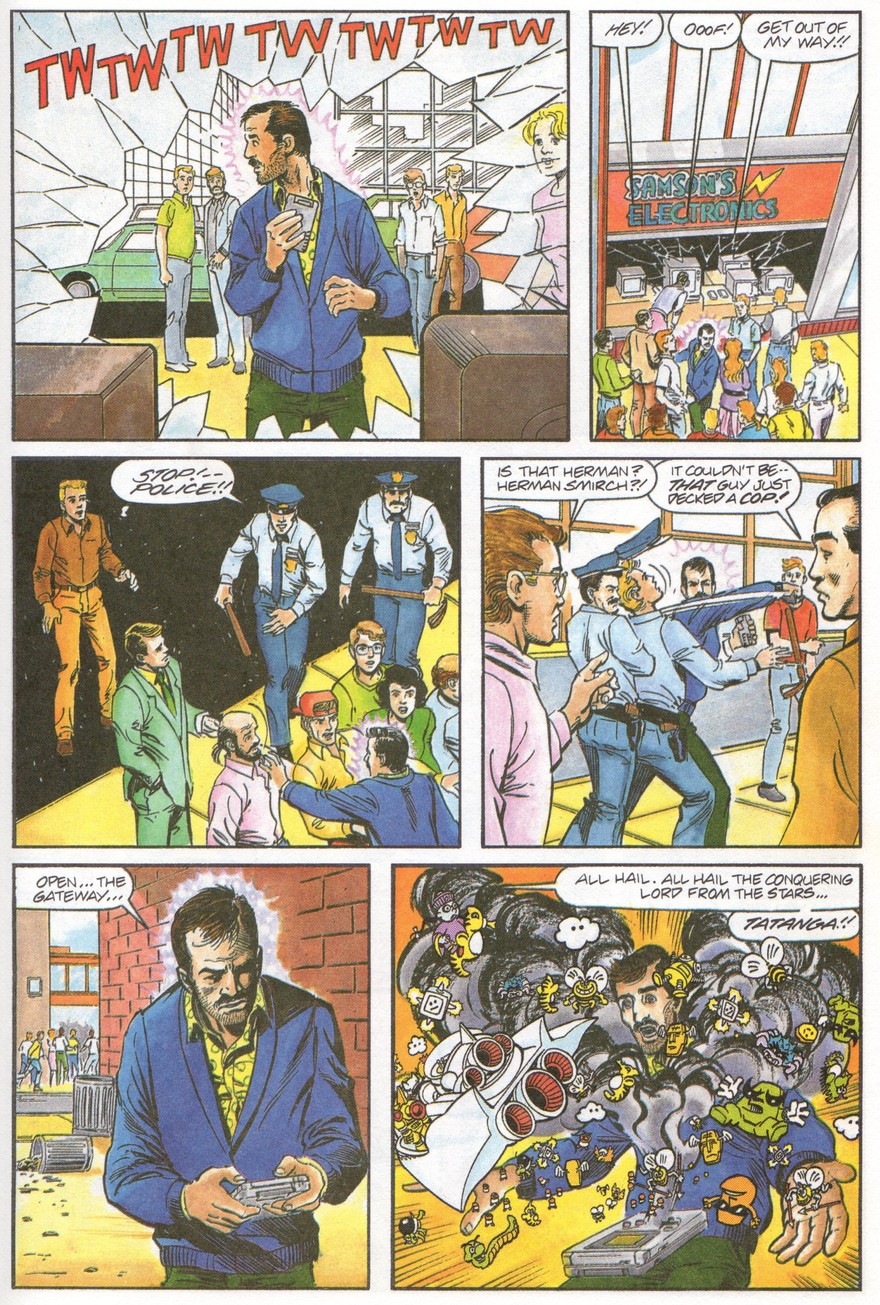

It seems the videogame villain has been looking for a way into our world for some time, and having such a “weak-willed, bitter and hateful” mind such as Herman’s is practically an invitation for Tatanga. What follows is a forceful invasion of a New York mall and the World Trade Center by Tatanga and his forces. The miniature army uses intense munitions and explosives to evacuate and subjugate the populace, causing dire injuries to any human that would oppose the tiny overlord.

The illustrations for these scenes are also unlike the other stories in the Nintendo Comics System. Realistically detailed people and recognizable environments sustain serious damage while a videogame villain ruthlessly invades. There is no cartoon mirth or comical whimsy behind these moments; this is a real attack on our world from an alien threat. All the while, Herman Smirch is hypnotized and coerced into serving as a liaison to Tatanga and his army. Until two teenage boys manage to bring Mario into our world to fight back, the only image of a videogame player is a hateful introvert who wishes ill intentions on his fellow man.

These comics continued for four issues, across which the ill-begotten Herman would summon Tatanga to our world, usually under the influence of a Game Boy. The action contained within would completely abandon the guidelines and restrictions set by most Nintendo standards. Over the course of the comics, Herman would use a brick to shatter the window of an electronics store, openly steal a Game Boy, and assault a police officer who tried to stop him from freeing Tatanga. Via the command of videogame characters, Herman stole a semi-truck, hijacked a plane, and kidnapped a young girl. This was such a contrast to the playful comics and cartoons of the day, where Nintendo properties told humorous stories and encouraged kids to purchase and enjoy their wares. Instead, the readers were presented a tale where Nintendo products were used to influence violent deeds and summon terrible warlords to conquer our homelands.

In spite of all the violence and negative themes present in the Game Boy comics, the series still managed to earn Nintendo’s coveted seal of approval. At the time, there did not seem to be a clear purpose for the different content in the Game Boy comics. There was no push for Nintendo to target a more mature demographic, particularly not with their flagship mascot and his latest videogame adventure. Whatever the reason, the Nintendo Comics System lasted for just under two years, until 1991, when the license ran out. Just like Mario in the Valiant Comics, Nintendo swooped in to banish Tatanga and his darker intentions, and all their precious properties returned to a kid-friendly status quo.