In January 2003, the Counter-Strike community was having a little trouble with something called “fakelag.” Less equitable players, of which there were (and are) many, were exploiting a command before joining a server that allowed them to simulate an artificially high ping, or fake lagging. This hack made players very difficult to hit. Entire clans of fake laggers were storming through matches like a horde of spastic undead. Something had to be done.

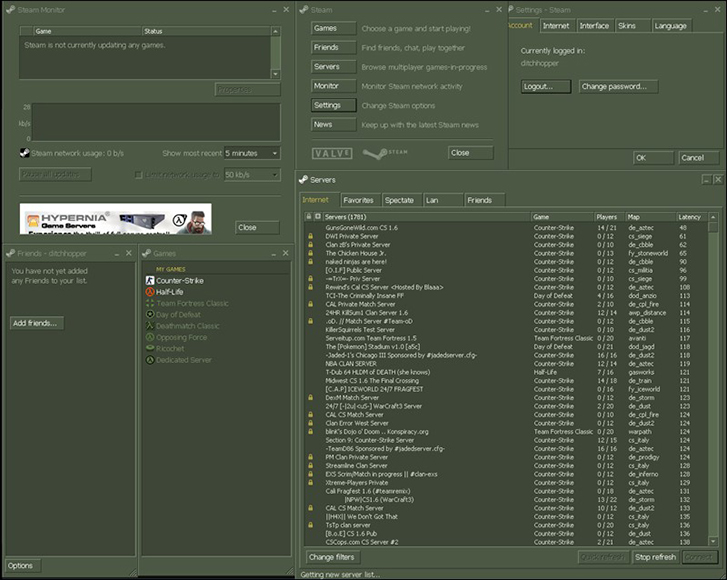

This should have meant more bad news. Back then, whenever Valve wanted to patch their online games, the update would often result in significant user disruption. Luckily, in January 2003 Valve had just launched Steam as a mandatory install for Counter-Strike. Through Steam, the 1.6 update was seamlessly disseminated, killing “fakelag,” along with dozens of other small problems.

Flash forward to 2014. You’re a developer, a major company or two-guys-in-a-garage, doesn’t matter. But you’re a good developer: the game you’re making is interesting, and people care about it. This your fancy new toy, and it has a lot of moving parts. Put it in a room with thousands of fiddling hands, and something is bound to break. What you need is the ability to walk in and say, “I see what you did there,” then take your toy back, tweak a few things, and make sure it doesn’t happen again. You need this same ability to update and patch.

This is what Don’t Starve, along with thousands of other games, now enjoy. The top-down survival game enjoyed significant success following its release on Steam in April 2013, eventually leading to a PSN port. Seth Rosen of developer Klei Entertainment says Don’t Starve was originally developed as a Chrome Store App, but the promise of Steam’s openness swayed them.

“Steam’s system for pushing out updates and patches is extremely easy to use and, importantly, free,” Rosen says. “This meant that we could keep to the rapid pace of development and [our] frequent release schedule.”

Giving developers complimentary access to their own games after going live may seem like a no-brainer, but until recently it was not an industry standard. In 2012, Fez developer Polytron declined to fix a bug in their popular Xbox Live Arcade game because the patch would cost tens of thousands of dollars.

“Had Fez been released on Steam instead of XBLA, the game would have been fixed two weeks after release, at no cost to us,” said Fez creator Phil Fish back in 2012. “And if there was an issue with that patch, we could have fixed that right away too!”

To their credit, Microsoft did not remain tone deaf. Soon after the uproar surrounding Fez, XBLA followed the way of Valve and removed update fees for developers, a policy which stands for the Xbox One as well. Sony also does not charge update fees for the Playstation 4.

“Openness” is a winning ticket for games platforms, one that can help maintain a large consumer base on both the PC and now console market. Steam’s supposed great virtue is that it offers its streamlined update and distribution system to all games on the platform, regardless of developer clout. For all intents and purposes, Valve has kept to this promise. But getting a game up on Steam, let alone promoted, still may not be as open as some may have you believe.

Valve has touted Steam Greenlight as a truly democratic arena for developers to get their games distributed on Steam. The system is fairly simple: for a small fee, anyone can submit their game concept, screenshots, and gameplay footage to be voted on by Steam’s participating user base. If a game crosses a certain vote threshold, it will be picked up and distributed.

Problem is, even if Steam itself does not practice preferential treatment based on developer clout, people invariably do. As Rosen points out, “The popular kids get picked first.”

“It’s hard to say whether that is because the people who have already known success are getting voted up,” says Rosen. “Or games that leverage popular themes or aesthetics are getting a higher percentage of up-votes, or there is some secret Steam Illuminati of voters controlling the polls or something. But that seems to be the perception of the system.”

For all Steam’s openness and power, then, it remains a somewhat closed ecosystem. That power is great if you can get in. But it’s unclear how a platform would go about removing this hurdle. Keep a completely open door? If you think Steam has discoverability problems now, imagine if literally every single C- computer class final project had its own Steam page. The system has its kinks, sure. But perhaps that too can be patched.