This article is part of PS1 Week, a full week celebrating the original PlayStation. To see the other articles, go here.

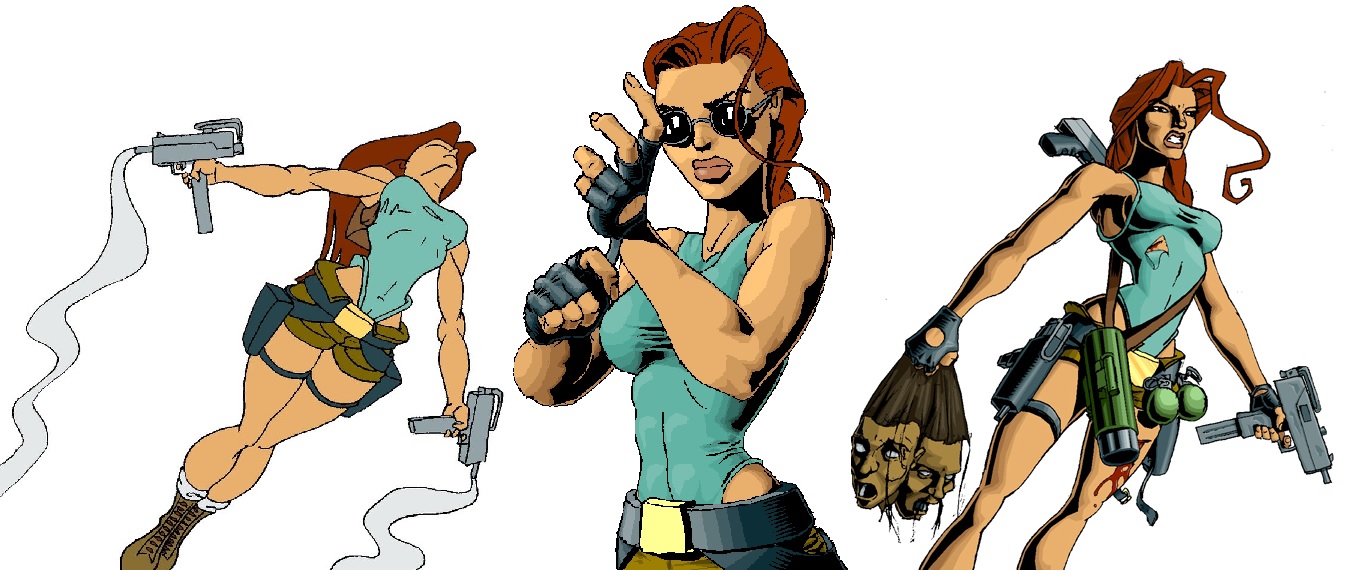

Header image: Toby Gard’s original drawings of Lara Croft

///

I never understood the fascination with Lara’s chest. Of all her 540 polygons back in 1996, those that formed a triangular prism as hard as granite under her jagged chin seemed the least relevant. I was more interested in how she gritted her teeth when firing her guns, or how she sighed with relief when being patched up with a medikit. She was the first videogame character I knew that showed her vulnerability: she had a horrific shriek when falling from a height before every bone in her body crumpled under the weight of her landing. I’m not the only one who felt her fragility. Games critic Cara Ellison has also felt it. She writes about Lara’s frailty, saying that she looked “thin and incapable,” and that she “was at the mercy of her environment. The fact that she had few supplies, little clothing, and nobody to help her: these made her task even more daunting.” But Lara was brave even if she wasn’t unafraid. She bled, and she leapt, hanged on for dear life, and throughout every dangerous situation we had to safeguard her—we wanted to.

Toby Gard, Lara’s creator, planned for her to have this effect on people: “That sense of protection is something that I didn’t think people had capitalized on in games before,” Gard told Critical Path. But what does the top-heavy crop top contribute to this? I don’t think Gard ever really managed to justify it to himself. He certainly tried. “The goal was to have her as an exaggerated representation of the female form. That was the reason why she has such an exaggerated, caricatured figure. Especially at that time when realism was impossible anyway,” Gard said in an interview for GameTap’s retrospective documentary on Tomb Raider. But why did Gard want to create a woman whose dimensions were impossible?

Gard is a man and so the answer may seem obvious: sex appeal. But, conversely, Gard told The Independent that she “wasn’t a tits-out-for-the-lads type of character,” and also said to Gamasutra that “you could argue that Lara, with her comic-book style over-the-top figure, is exploitative, but I don’t agree.” Considering Gard said all this after Lara had exploded into the “cybertart” (as Gamasutra referred to her) we all know, he could be accused of back-pedalling to save himself. But, in fact, he was so genuinely upset by the media’s treatment of Lara as a sex symbol that he left his job at Core Design. This was just before work on Tomb Raider II began. In the lead-up to that sequel in 1997, Lara Croft reached the peak of her popularity; simultaneously a PlayStation icon, and the host to a debate that divided feminists and critics. From almost every angle—especially the flattering ones—Ms. Croft was a huge success. So why was her creator unhappy?

Lara was originally a man—practically an Indiana Jones rip-off—which is why the management at Core Design said Gard had to make big changes to his lead character. Gard needed an original protagonist, one that would shake things up, and that’s why he cast a woman in the starring role. As Gard explains in GameTap‘s documentary, the majority of mainstream videogames before Tomb Raider had portrayed women as objects (“damsels in distress, or just terrible fantasy dominatrix-y type of characters”). They were restricted to playing supporting roles (with only a handful being the exception, including Metroid’s Samus Aran), and were almost always subservient to the leading men and the gaze of the assumed male player. This is why Eidos, the publisher, took some convincing on the idea of Lara Croft. She not only took what was traditionally a man’s role, she was a strong woman in her own right, dangerous, intelligent, and attractive. In Tomb Raider, we learn that Lara is a freelance adventurer and archaeologist, and she plays for sport over money, meaning that her time is as flexible as her body. She’s independent outside of her job, too, as she has recently moved into an expensive mansion that she bought for herself, alone. Her hips are not for bearing the babies of any man she may fall in love with; they are where her gun holsters lie.

In creating Lara Croft, Gard looked for inspiration in Tank Girl’s use of space rockets as a bra, owning her body’s objectification by brandishing her promiscuity and punkish fashion sense as a boisterous threat. She frequently fucked, farted, and fought, and did so autocratically. But to understand Tank Girl, this hyperbolized comic-book character, and what Gard had transferred from her into Lara Croft, we need to look at the political climate that they emerged within. The ’90s, a decade that wore “Girl Power” as a strap line, was host to the third-wave of feminism. According to Bitch Magazine, this movement was spurred on in 1989 by NOW (National Organization for Women) president Patricia Ireland as a “response to increasing federal and state restrictions on abortion.” This was the effect of a decade-long backlash against the public face of feminism, and a growing activism among young women at the time. It gained momentum quickly: in 1990, author Naomi Wolf deconstructed the expectations placed on women’s physicality in “The Beauty Myth”; in 1991, Susan Faludi contributed a polemic on the media’s efforts to reverse the efforts of second-wave feminism in “Backlash“; and, by 1992, the Third Wave Foundation (initially the Third Wave Direct Action Corporation) was formed to centralize this new cloud of feminist thought regardless of gender, race, sexuality, and class. It was a time of girl riot (and riot grrrls) and feminist expression that looked to demolish the double standards separating genders, and the treatment of women by the media and the law.

Riot Grrrl zine, via Jacobin

Despite condemning writing such as Faludi’s book, it didn’t take long for the mainstream press to find a part of third-wave feminism that it could spin for its own cause. Some third-wave efforts pushed towards reclaiming traditionally girly activities—sewing, cooking, sex-talk, make-up—in order to reinstate their value rather than erase it. Part of this was celebrating feminine beauty and the bodies of women, which the press saw as a crutch to explain its continual exploitation of women and their bodies across their glossy pages. If anyone brought it up, the media could use the moniker of feminism as an unwilling scapegoat. With this, the grassroots origins of third-wave feminism were essentially chewed up into a commercialized phantom of itself.

By 1994, this warped understanding of feminism by mainstream conversation had become so visible that men’s magazine Esquire felt the need to jump in and coin it “Do-me feminism” (also called “bimbo feminism,” “lipstick feminism,” and “babe feminism”) in an article titled “Yes: Feminist Women Who Like Sex.” The article picked out sex-positive feminists such as Naomi Wolf, sex educator and porn actress Nina Hartley, and shirt-pulling musician Liz Phair, to draw together a supposedly new type of feminist that it saw as emerging around that time. The issue with this article, as Andi Zeisler writes for Alternet, is that Esquire led with the presumption that all feminists, by default, didn’t like sex. Specifically, it portrays the second-wave of feminism as nothing more than women who hated men. And this is only due to them protesting the idealized image of a beautiful woman as purported by the media. It was articles like this that sowed the seeds of a generational antagonism that was perceived to grow between feminists of the second-wave and those more akin with the third-wave. It was old versus young, sex-averse versus sex-positive, and men-hating versus men-friendly.

The idea spread through the media like wildfire. It seemed to reach its apex on June 29th, 1998, when TIME magazine’s “Is Feminism Dead?” cover was published. It put the prominent (and natural-looking) faces of feminism of the previous 150 years (activists, journalists, social reformers) in black-and-white, deliberately in contrast with the color photo of TV’s fictional lawyer Ally McBeal. Her gloss-red lips matched the font of the cover’s damning question underneath her portrait. But this result doesn’t seem to be the aim of Esquire‘s 1994 article and those like it; it was only a festering by-product. Instead, Esquire seemed to be handing out a memo to inform its male readers of these feminist floozies that might want to have sex with them. “And thus, a new feminism entered the mainstream—leading with its breasts—and became a key example of why feminism just couldn’t be easily translated into mainstream media formulas,” writes Zeisler.

This leads us to Lara and her large triangular chest. I think Gard saw Tank Girl and wanted to create a woman with similar strengths, but with a measured dose of mannerly austerity, and quiet intelligence. Lara was intended to be a step forward, if not for feminism, then at least for the representation of women in videogames. Gard also wanted to make sure that Lara was easily identified as a woman by the executives looking over his shoulder. Her chest, long legs, and big lips are Gard’s way of signposting that she was definitely not Indiana Jones. All of this had to be squashed within the graphical limitations of the hardware to hand. Console and PC technology at the time excelled at jagged 3D. Hence, Lara was formed out of sharp inward cuts rather than more true-to-life curves. But what he may have seen in Lara was different to what the marketing department saw. They must have been aware of the mainstream media’s usurping of third-wave feminism—that was part of their job—and therefore saw potential millions in pushing Lara Croft as a sexy feminist icon. Men could ogle at her while women may find representation and strength in Lara.

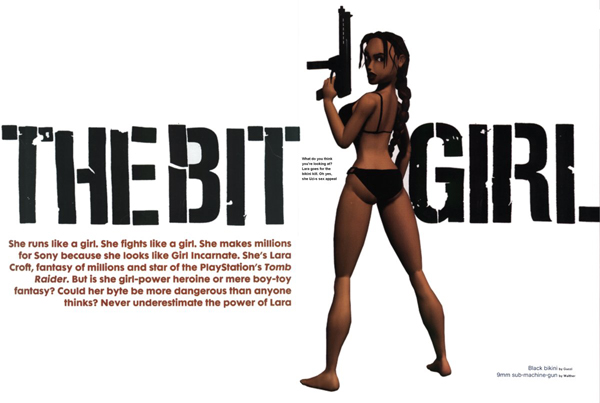

And so it was. Lara slipped in among the Spice Girls, The Vagina Monologues, men’s lifestyle mags like Loaded, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Bridget Jones’s Diary, “ladettes,” Xena: Warrior Princess, and Courtney Love. Most of these women were portrayed in the media in dual roles: they subverted gender norms by taking what were usually positions filled exclusively by men, and they were also deemed physically attractive enough to be worshipped as if Aphrodite herself. With Lara, Gard captured the zeitgeist in one controversial package, whether he meant to or not, and the media lapped it up. According to Newsweek, Lara had appeared on the cover of over 40 magazines by November 1997. The Lara that Gard had created, the vulnerable but brave woman, was gone.

Once Tomb Raider was released in October 1996, it went on to sell seven million copies across PlayStation, Sega Saturn, and PC. Lara was thrust into fame as a dichotomous entity, being both a feminist icon, and the latest pin-up girl. By June 1997 she was on the front cover of The Face magazine. The words “Silicon Chick” were to the right of her, “Bigger Than Pammy, Wiser Than Yoda” to her left, and smack bang in the middle was her 24-inch waist and 34-inch chest (38-inch in the US). The mainstream media had found its perfect woman: Lara Croft was a cyber gal who could pose perfectly every time, say whatever brand name they wanted, and would never show signs of aging. This is not what Gard had wanted for his character. He was the lead designer and artist on the first Tomb Raider. He handled story development, storyboarding, FMV generation, in-game animation, character design and modeling, level flow, title and load screens, box art, and marketing materials. He went from having full control over Lara’s image to losing it entirely.

And it wasn’t just the mainstream media that stripped him of his creative control over Lara. Being among the first cyber stars, Lara Croft was at the mercy of digital-age media, making her malleable in a greater way than the stars that had come before her were. As such, the reconstruction of her body and the politics it may represent was rampant among her fans, perhaps even moreso by them than her marketers. By the time Tomb Raider II was released in October 1997, promotional materials had Lara blowing kisses at the camera in a revealing bikini, while fans stripped her of clothes entirely with nude patches and fan art. “I had problems when they started putting lower-cut clothes on her and sometimes taking her clothes off completely,” Gard told The Independent. “It’s really weird when you see a character of yours doing these things. You can’t believe it. You think ‘She can’t do that!’ I’ve spent my life drawing pictures of things and they’re mine, you know? They belong to me.”

Perhaps Gard was naive at the time. On the back of Tomb Raider‘s box, the one that ended up in shops, he had put “Sometimes a killer body just isn’t enough.” And so magazines such as The Face seemed only to be paraphrasing his own words. On the other hand, you can see what he was going for: Lara was no bimbo; despite any impression her appearance may give, she was intelligent and she was deadly. There were fans—girls and women, most notably—that saw this empowering side of Lara and ran with it. People like Katie Fleming, who created the most popular Tomb Raider fan site, and won competitions for her fan fiction. And cosplayers such as Chantal Slagmolen, who started out as a hobbyist Lara lookalike, but was eventually hired to appear in costume at big events. Even my sister and I role-played as Lara in our back yard; one of us the wolf, the other holding invisible guns and wearing a bandage on their arm. Fans created all sorts of artistic materials, fictional spin-offs, and acts of fandom around Lara Croft, and they still do. “People discuss and share Lara Croft and it’s now up to you, as an individual, as to how you see her. Her treatment in this way is prescient of what would happen with videogames and their stars over the next two decades, and beyond,” writes Hamilton College.

Lara was the catch-all girl for the ’90s; her body a canvas for your interpretation. She was the start of a line of virtual women in videogames that would have their bodies divided by arguments. These days we have Bayonetta splitting the same opinions that Lara started to do 20 years ago. Like Lara, Bayonetta is an independent woman, and the star of her own videogame series. She’s strong in mind and body, but also overtly suggestive: she blows kisses, poses for the camera, and strips naked to unleash her most powerful attacks. She has all the hallmarks of a third-wave feminist icon, albeit ramped up to a ridiculous level. We’re no better settled on the issues now, though. Why can’t a woman look good and flirt if she’s doing it on her own terms? These are the same questions that Lara provoked back in the ’90s. It’s what made her a PlayStation icon.

Since Tomb Raider IV: The Last Revelation, in which she was killed off, she has undergone a Pinocchio-like transformation, finding herself closer to a real woman. She has been steadily losing those pointed breasts—they developed curves, were shrunk. These days, particularly with the Tomb Raider reboot, she’s closer to possessing a believable body. And with that caricatured figure shedded, Lara has started to rediscover that vulnerability she once showed, and that the mainstream media never saw.