David Cage can be infuriating.

As someone who studied film but now writes about videogames, I’ve partly relied on him—one of the most outspoken advocates of merging cinema with games—to discuss the potential in bringing cinematography, and other cinematic techniques, into games. He has helped to define what the term “cinematic” means in videogames since sharing his vision for his 2005 game Indigo Prophecy, which he’s admitted was heavily influenced by the cinematic storytelling techniques of 2000’s Shenmue. I, and many others, have been ensnared by Cage’s ideas, and have been waiting for him to push them further, to find a seamless blend of cinema and game that takes us down new paths.

But I’ve been let down, time and again. And Cage has become skilled in making excuses for his failings to merge the two mediums.

“Photography was at first influenced by painting; film by theater. It took time for these media to evolve their own identities,” Cage told Gamasutra. But it’s not time he needs; it’s a complete overhaul in approach.

Cage’s obstruction is his genuine belief that in becoming visually identical to cinema, videogames will reach a point of ascendancy. Only then, he reckons, will we be able to feel emotion in games. He speaks as if no one’s ever wept or smiled by a game’s story and characters. In that same Gamasutra interview he actually said: “I don’t know if we’ll get to the point during this cycle where you can’t tell the difference between a film and a game but we will get very close.”

This is why he calls himself a director, why he employs Hollywood actors, and spends weeks in motion capture studios, spilling huge budgets trying to encapsulate a real human’s movements, facial gestures—their soul—for a cutscene.

Since Indigo Prophecy, Cage has delivered two more efforts: Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls. He believes he’s getting closer to his vision. But these last two videogames can be condensed to lengthy animated films with prompted button pressing (and sometimes rapid mashing). You steer conversations from a limited set of options, and hit buttons at the right time during action-based sequences.

It’s the same technique that Yu Suzuki used to fuse gameplay with movies in Shenmue. During his Shenmue post-mortem at GDC 2014, Suzuki said his reasoning for the design that Cage has since made his own is that quick-time events are interactive but match the visual quality of cinema. They’re easy, even for those without skills in timing or puzzle solving, perhaps even non-players, and therefore support a wider audience.

Back in 2000, this laid new ground for the potential of interactive storytelling. Cage incorporated it into his own design but hasn’t ever really done anything to push it forward in the decade since. Technological achievements his games might be, yes, but that’s about it.

It’s frustrating for me. I want Cage to be better, to show how cinema’s influence (and the influence of other mediums) can lead to different forms of interactive storytelling in videogames. He needs to look beyond visual quality. I’m not ready to tell Cage to just merge with Hollywood and make films already, but I can’t help but feel the same disappointment of those who do. So, like any hopeful person, I’ve looked elsewhere for a better solution.

People often point to L.A. Noire as a “cinematic” game, but that’s a bigger mess than even Cage has ever managed. Its open-world design is undermined by its strictly linear story; there’s nothing to do outside of it in the whole of 1940s Los Angeles. Its much-touted animation technology brought nuance to facial expressions, but your conclusions are funnelled through a few basic reactions: Truth, Doubt, Lie. If you stepped a foot out of line (almost literally) during some missions the game swoops in like a director yelling “CUT!” At best, L.A. Noire is an awkward fusion of videogame and cinema, but it still attended the same class that Cage did.

Metal Gear Solid is usually next on the list. Again, cinema and videogame coexist but are not merged. There’s a very distinct difference between the lengthy cutscene and playing as Solid Snake. The best blend of the two mediums I’ve found is Remedy Entertainment’s co-opting of bullet-time from Hong Kong cinema for 2001’s Max Payne. It didn’t do anything for the narrative, but the slow-mo dive shooting was resolutely of the moment. But even that has failed to evolve in over a decade. Take a look at the recent Max Payne 3 as a gruff man floats down stairs, guns at arms-length, as if it’s how he learned to walk. It’s a parody that writes itself.

At my most desperate during this search I’ve typed in “cinematic games” into Google Images, which brings up screenshots of Uncharted, Gears of War, Assassin’s Creed, and Halo. These are the games that are most widely known for being “cinematic”—and, not coincidentally, are also the most widely known games.

But what’s so cinematic about them? That’s a $1,000,000 question. Wildly swinging camera angles, dramatic action sequences, orchestral music, near-invincible protagonists, and—in between the chaos—gorgeous vistas all seem to tick the box. The term cinematic was previously confined to games that used live-action film, animated cutscenes, or were direct movie tie-ins. Now it can be applied to almost anything melodramatic.

There’s no solid definition of the term because it has no finite meaning. Writers, journalists, developers, and marketers fling it about wildly in bold lettering. It sells grand ideas on par with IMAX and Avatar. New technology, new experiences: cinema is cutting edge and it’s big-screen entertainment. Ultimately, though, it’s just another piece of language we’ve robbed of meaning, like “next-gen,” “indie,” or “unique.”

I can’t bear to see cinema’s influence on videogames being completely lost to the pit of jargon. It’s not too late to reclaim the term “cinematic gameplay” if we use it with proper cause. I’ve been pleasantly surprised to find cinematic techniques reapplied in a few videogames over the past couple of years.

Blendo Games employs the jump cut in Thirty Flights of Loving to create a punchy rhythm and startling pacing. The cuts replace the inactive viewing of cutscenes and the pointless walking between locations and events. More importantly, these deliberately juddering cuts link moods and actions of characters between disparate events, adding an extra layer of meaning to be read into. The use of jump cuts has the same refreshing surprise that Godard’s did in À bout de souffle (Breathless).

During one scene, after a disastrous armed heist, you’re trying to save the life of a friend and fellow criminal who has been shot, while also escaping the long-reaching arm of the law. You’re hurtling through corridors full of bustling people, at first carrying your wounded buddy over your shoulder, and then dumping him onto a trolley for mobility. The entire journey is fragmented—you jump from corridors to rooms and then back—creating a sense of panic that wouldn’t be as distinguished without the jump cuts.

Unmanned, by Molleindustria, makes excellent use of split-screen to portray a day in the life of a conflicted US army drone pilot. It starts with you watching him sleeping in bed on the left side of the screen while his dream plays out on the right. Later, you share his gaze across a blue sky over a rocky desert while simultaneously instructing his puffs on a cigarette from a side-angle. While shaving his face, you have to be careful to not cut his skin as you juggle with choosing from a list of thoughts about the day ahead.

The split-screen isn’t solely a stylistic choice in Unmanned, as developer Paolo Pedercini explained to Ars Technica:

“Yes, disconnection is a theme that runs all the way through Unmanned. It is embedded in the split screen and dual gameplay that reflects the schizophrenic life of the protagonist, and in the characters’ lives as well: in the father and son’s difficult bonding, in the protagonist’s potentially challenging relationship with his wife.”

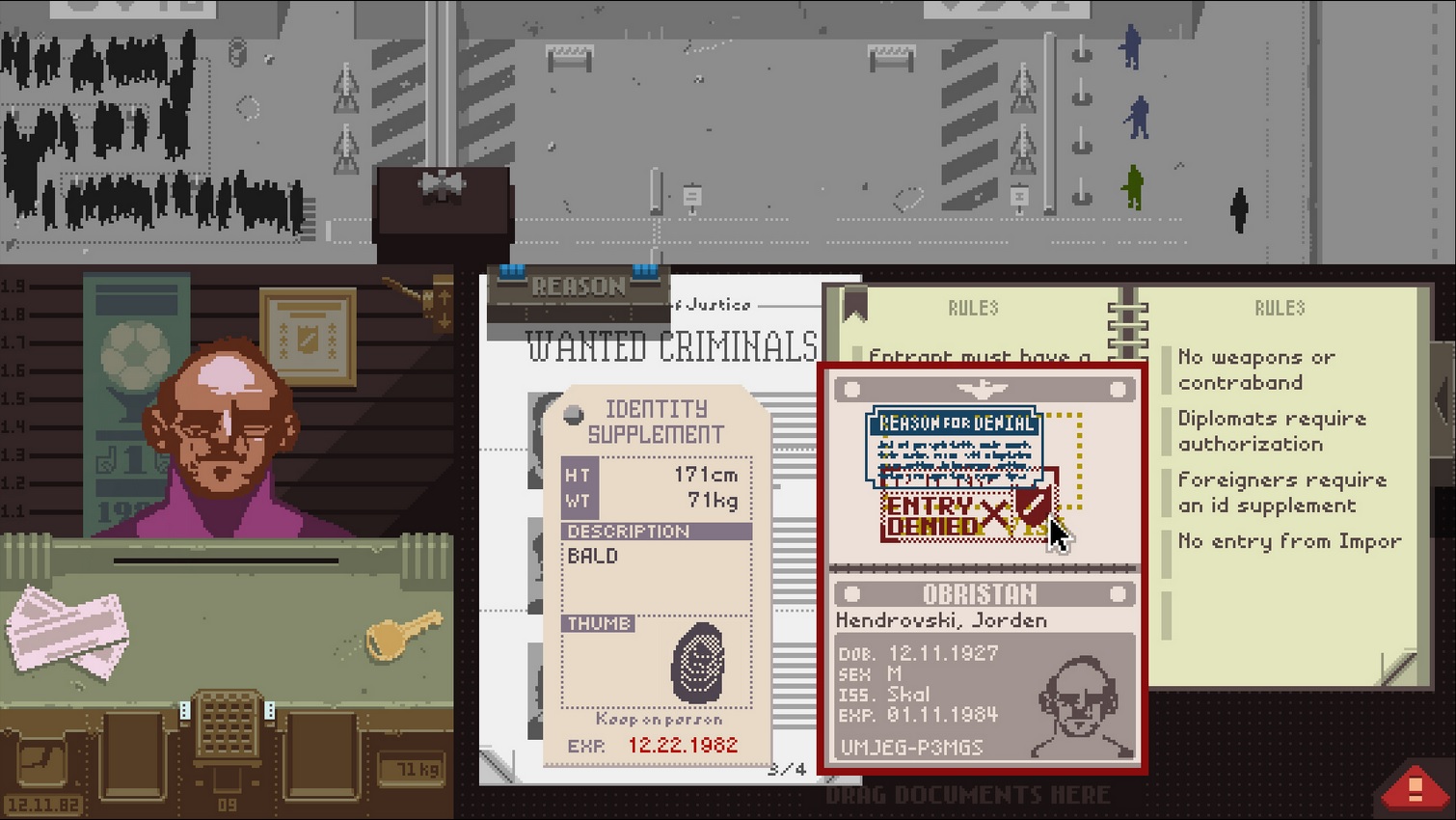

Papers, Please uses multi-frame narrative to, as developer Lucas Pope told me, “force the player to divide their attention” while inspecting identity documents at a fictional Eastern Bloc border checkpoint. This is the same technique used by Mike Figgis in his four-way split-screen film, TimeCode.

Discussing the poetics of multi-frame film—using TimeCode as an example—interactive narrative and game design lecturer Jim Bizzocchi says that while all cinema is interactive in terms of having to interpret what you’re viewing, split-screen cinema demands a higher level of interaction. With split-screen you have to interpret the separate events occurring in two or more frames simultaneously, and on top of that, you also have to read into the meaning of the relationship between those frames.

Papers, Please is presented in a three-way split-screen. Without even laying your hand on a computer mouse, the visual interface of Papers, Please is encouraging you to interpret how each of these frames interact with each other, just like a film. But there’s a lot more to Pope’s application of the technique than just complicating interpretation.

Bizzocchi also says of multi-frame narrative that it “offers a visualized version of increased narrative bandwidth. This style of presentation puts more pressure on the viewer to actively work in order to keep up with the story.”

It’s ultimately this sense of pressure that defines Papers, Please. The game’s challenge is found in darting your eyes across the screen, relaying information and checking that it all matches up: country of origin, height, weight, gender. This is only made possible due to the concise 2D interface design, which splits three areas into a single screen.

“In the real world, a border inspector can see those three elements from their seat: the queue, the person they’re processing, and their desk,” Pope told me. “If it were a 3D first-person game, there’d be no question about how to represent this. As a 2D game, I wanted all these elements visible at once to simulate that first-person perspective.”

But this concise design soon lends itself to cramped spaces that too easily become messy as more lists, scans, and supplements are added for you to track. Later, you’re given the pressure of watching out for terrorists who jump the wall in the top frame, and told to shoot them. Now, getting distracted isn’t just a nuisance; it’s vital if you are to save lives.

The multiple frames of Papers, Please allows for visual distractions and crammed spaces that exacerbate the multi-tasking the game requires. It’s your level of success in this spatial performance that determines the game’s narrative outcome. If you don’t keep up with the interconnections, either you or your family will suffer the consequences—it’s often not a case of Game Over—and they don’t come lightly.

However, I wouldn’t call the multi-frame narrative of Papers, Please “cinematic,” despite it using a technique that is also found in cinema. For a start, the root of splitting a screen up can be traced back to the art of composition and spatial interconnection in painting, so it’s not entirely a cinematic idea. Secondly, I’m pretty sure that Lucas Pope didn’t directly borrow from cinema as Cage so lavishly attempts to. The point is that he used multi-frame narrative beyond what any film has done with it, and will ever be able to do.

This is exactly what David Cage has been looking for when trying to merge cinema with videogames. Here we see a developer creating a unique, videogame-specific language from a cinematic technique. This is what Cage yearns for: advancing the medium, discovering new grounds in videogame narrative.

Papers, Please doesn’t have motion capture or laborious animated scenes, nor was it marketed with the promise of being cinematic. The same can be said for Thirty Flights of Loving and Unmanned. But, perhaps more than any others, these games manage to successfully and seamlessly blend cinematic language with gameplay. In fact, the blend is so good that you have to work at finding the cinematic root within them. But it’s there, and it’s a testament to the potential of learning how other mediums relay information and interact with their respective audiences, and experimenting with it in games.

This is only the beginning of what a wider understanding and incorporation of cinema could unlock. Dismiss David Cage’s games if you must, celebrate them if you wish, but know that there is more to “cinematic games” than what the term is currently applied to. We just have to find it. We’re starting to.