This article is part of a collaboration with iQ by Intel.

Even if you believe that men should appear stone-faced serious in pictures, like so many old-time photographs of cowboys, gangsters and butchers, the phrase “smile for the camera” will likely never go away.

Cameras are impartial, even downright dispassionate mechanisms that could care less whether or not you are smiling, but new 3D camera technology might make you think twice about flashing a grimace or grin at any given moment. That expression could change the next scene you face in that otherworldly game you’re playing. It might bring your fun to a quick, lethal end.

With the rollout of Intel RealSense this fall it could be said that our next computers will be emotionally well-adjusted—maybe not in and of themselves, but on our emotions. They could soon understand our facial responses as easily as they understand the keyboard and mouse.

Those tiny, round lenses built into future desktop, laptop and tablet devices will learn things about us. They will learn what you look like when you’re having a good time, when you’re lost in quiet contemplation, when you’re on the verge of throwing your expensive electronic device out the window because you can’t beat level 22 of a videogame.

Chuck McFadden at Intel is in charge of making these high-tech next-gen cameras fun to play with, and that includes using their facial recognition functions to let game designers in on a little secret called our feelings.

The project is still in the early going—the software developer kit, or SDK, recently entered beta—but it has already telegraphed emotions that are universally recognized. Blind rage and full-blown shock are easy to identify, McFadden said.

The trickier part is pinning down softer emotions, emotions we might not even have names for, that are conveyed through “just a very slight frown,” he said.

McFadden sees a time in the distant future when smart cameras can pinpoint thin layers of emotion perhaps better than human eyes.

“If I’m looking with the naked eye, I don’t necessarily see a profound change, but subconsciously I can tell when [someone] is feeling down, even if I can’t necessarily place it. That’s the holy grail of emotion detection,” he said.

We all know computers have made big, long strides at doing things that would shock people from earlier eras. They can talk. They can respond to touch. They can concoct mystifying culinary dishes such as pork belly Czech moussaka. But empathizing with our species, or presenting the illusion of empathy, has always been a hard spot. One only needs to think of the bizarre human-robot interactions with Bina48 to see my point, and she’s one of the more advanced androids out there.

That said, these cameras are aiming to be emotionally intelligent, not self-aware. What’s actually going on when they read your face is that they’re matching up your furrowed brow and pinched nose to a vast database of furrowed brows and pinched noses inside the computer, allowing the game designer to string things together so your facial gestures pierce into the game itself.

The tech is brand new, so for the time being we can only talk about potential. McFadden admits that facial scanning technology is at the beginning of a long road, a road that leads to unfamiliar places, but ultimately an exciting road that leads to the future. “I’m personally interested in what else we can do. Can we see the surprise? The confusion? And if we can see that we can give you potentially really subtle but much more engaging interaction,” McFadden says.

Some examples off the top of his head include reading puzzled expressions on confused players’ faces so that the game can offer tips and tutorials. Also, horror games could reading your looks of anxiety to learn the precise moment when you are susceptible to jump-scares, which sounds terrifying.

But that’s only the beginning.

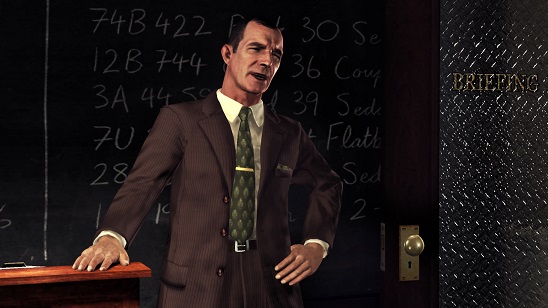

In a game like LA Noire, where you interrogate suspects by reading their facial reactions, the characters would also be able to read yours, said McFadden. Exchanging dirty looks with convicts can get so real that you forget you’re staring down a computer, a point at which the camera will learn a new facial expression, one of fear plus wonder. It’s worthy of a new term.

Emotion detection has the potential to make our interactions with technology more convenient, and less manual. Imagine, for instance, a radio app that noticed your look of resentment when it played The Eagles and knew to never do that again. But perhaps it could also help us express our emotions more clearly in the digital world. After all, Facebook is a catalogue of the faces of friends, but we never really exchange genuine emotion with them. What if there was a little smile notification that popped up when someone laughed at that cute picture of your collie wearing a graduation cap? It could make computer interfaces more friendly—literally.