A conversation with Ian Dallas, creator of The Unfinished Swan

The Unfinished Swan is your first game. What were you doing before?

My background originally is as a comedy writer. I worked at The Onion straight out of college, and then in TV as a writer’s assistant, and a writer on some animated stuff. But my interest has always been in creating things that surprise people, trying to make the world a more interesting place. I feel like there’s so much out there that is repetitive, comfortable, and familiar. I just want to create something that people have never seen before.

I started out initially working in comedy and TV, always expecting that I’d eventually move into game development because I’ve been super interested in games from a very young age. I thought that I’d do that as a writer, but it turns out that you really can’t make a game as a writer. The way that games are done, writers are brought in at the very end to polish the script, but they don’t really have material contribution generally. So I went from working in TV to writing on the Sam and Max series by Telltale Games. That was an easy transition [laughs] from writing to…writing!

Then I went to grad school at USC for game design. That really gave me a chance to take a step back and teach myself a bunch of things about programming, 3D modeling, animation, all the kind of basic building blocks for how games are put together. And then, yeah, I built a prototype that Sony saw and they were interested in making it into a full game. And a little more than three years after that, here we are with a game!

My first experience working in videogames was actually as a tester.

Oh god. I’ve heard that’s a horrible job.

Yeah [laughs], I think it’s a great job to have for a little while. And that’s what I had it for, and I’m really thankful for that experience. TV shows are not full-year things; you have a break in the middle usually. I had a couple months free so I was just like, “Ok, I’ll be a tester!” It’s an interesting environment, to be playing the exact same game for a month or two. It gave me insight into what the mindset is of the tester when we were doing QA ourselves. That was a funny intro to game development.

Were you doing very stereotypical QA stuff—walking around a room trying to find all the possible ways to break a game or something like that?

There are two cliché things that any tester will do. One is trying to jump out of the world. Videogames are set up with these invisible walls in places to try to keep people inside them. You want the player to think that the world goes on forever, but really on the other side of that building it’s just emptiness. You fall forever. It is a kind of hell.

As a tester, you’re basically probing for weakness. So if you actually find out, “Oh, I can jump on top of parking meters and then use that to get on top of lamp posts, to get on top of the flower box, to get on top of the building, and then suddenly I’m out of the world!”

The other thing that testers spend a lot of time doing is trying to recreate really subtle crashes. Bugs are defined by their reproducibility, so if you can get it 100 percent of the time, that’s great and generally pretty easy to fix. But sometimes there will be weird interactions of bugs where this crash only occurs if you’re wearing dragon scale armor, and have a cross-bow, and all these other weird things. You’ll get bugs that happen one out of every fifty times even when you have those things in place. As a tester, you’re the front line. I’m so thankful as a developer that we don’t have to spend all our time doing that.

Did any of that inform The Unfinished Swan? The game feels very openly technological, as if I was walking into one of the gray spaces you mentioned before and suddenly felt lost without the boundaries and borders you usually have in a game world.

I think the game is really about confronting the unknown. It’s interesting how different people take away very different experiences from that. It really just comes down to how you deal with uncertainty. Some people just run right off, kind of rolling the dice about what’s going to happen. And then other people really enjoy their ability to test things out.

In a way, it’s a game about the scientific method. As a player, you’ll have a hypothesis about how something works and what might be out there. And then we’re giving tools to test that. One thing we did a fairly good job of was creating a lot of different ways to interact with the game that are flexible. Generally in a game when you have a gun, there aren’t a lot of things you can do with that gun. You can’t sit there and shoot a tree for twenty minutes and cut it down. You can shoot the tree until hell freezes over and it will just never be affected by your bullets.

For us, all of the tools in the game, starting from the original paint splats, stick around forever. Which is a huge pain in the ass as a programmer to deal with. But it gives the world this aspect of the scientific method to it; you have these tools that you can kind of use in very flexible ways to probe the world and figure out what’s out there.

The game is really about confronting the unknown.

When I think of games that are designed to be funny, I think they’re very punchline-driven. The story in this seems more whimsical, almost like a fairy tale.

I wouldn’t say it’s a really funny game. It’s not intended to be. Comedy in games is super hard. Players have so many things they’re juggling in their minds already, that they’re just not in a very receptive state for jokes. Jokes also tend to be funny once. They take a lot of work, and are delicate; they’re like an egg, or something. Games and stories generally work a bit better when they’re flexible enough to accommodate the player approaching them in different ways.

It’s a really tricky thing, but at the same time there are some hilarious videos from games that I’ve seen, none of which are intended. In Skyrim, there’s a bug with the artificial intelligence where you can put cauldrons on top of characters heads, and then they can’t see you steal things. It’s so ridiculous, but also just delightfully surreal. Or another bug where you could create an infinite number of apples? You’d see these videos where people would just flood the world. That was one of my favorite things of the year.

There’s an amazing video where someone shoots an arrow straight up into the sky, then just sits down at a bench. A few minutes later, someone in the town square dies suddenly and everybody else just keeps walking about their business. It felt like something out of Monty Python.

That’s awesome! Yeah, I think games are a fantastic sandbox to create those kinds of experiences. But in terms of authored comedy, it’s a much rougher road to hoe.

What games do you remember playing? Which had a big impact on you?

Super Mario Brothers was one of the first ones that really grabbed me. I don’t know that I’ve had many experiences in my life that were like the joy of discovering that you could warp from level one to many of the other places in the game—you didn’t have to play from beginning to end. And just the fact that in a video game you could explore on your own and discover things that weren’t necessarily there. The world was richer than you would expect. Hopefully we’re creating that same kind of experience today, where kids can have that same moment of wonder.

The Unfinished Swan seems like it’s delivered from a child’s perspective, though not necessarily to one. Did you have anybody in particular in mind when you were creating this?

I think we were hoping to appeal to players that are interested in believing. That’s not a very specific audience [laughs]. And, really, there’s that old truism of making a game that you want to play. As a game player myself, what I really love are worlds that encourage you to explore them. They don’t tell you a lot about them. That’s really the experience we were trying to create. Really we found that in terms of actual demographics, the people that the game seems to resonate the most with are hardcore players, that play tons of games and are just kind tired of playing the same game over and over again. And then, conversely, people that don’t play any games, because they don’t have an interest in zombies or World War II or whatever games tend to be about. So we ended up with this game that appeals to people that play a ton of games, and to people that play almost no games.

How do you approach your work differently as a writer and as a programmer?

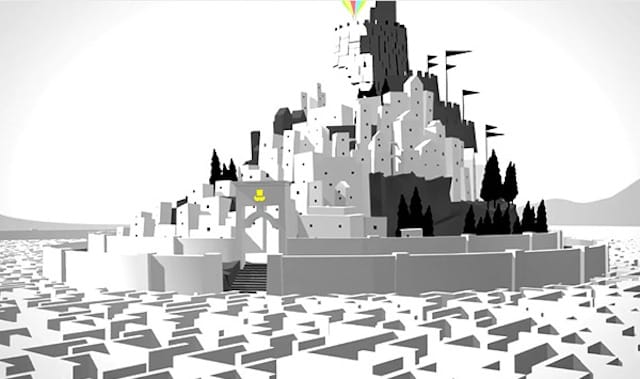

If I’m stuck on something, or if we’re trying to find a way to get players to approach, say, the giant labyrinth at one point in the game—as a writer you’re very limited by the tools you have. As a game designer, I can think of that same issue from the code level, and from an architecture level, from a bigger scale of what the player has seen five minutes before this. That is a much more enjoyable process for me—to be looking at the same kinds of problems from a bunch of different angles.

I think of it as the thing that writing teachers always told you to “show” and not “tell” something.

One of the things I think is interesting about our game is the amount of voiceover there is. For movies, voiceover tends to be seen as really lazy, like it’s the last defense for getting out exposition to the audience. For The Unfinished Swan, using storybooks as a reference showed me that one of the reasons they work is this contrast between you not knowing very much as audience member about this world, but then at the same time there’s a narrator who knows everything about it. The narrator’s omniscient, and you’re in this position of needing to hear about this world. The narrator will tell you some things, but then others will be deliberately obscured. And I think that’s true to the experience of a child; this world is incredibly complicated around you. And you trust that your parents know everything about this world, and that they’ll share a bit of that with you when you need it.